How Your Location Data Is Being Used to Predict the Events You Will Want to Attend

Recommendation engines have flooded the Web. It’s hard to buy an ebook, mp3 track or video without being bombarded with suggestions for other purchases. Indeed, the phrase “people who bought X also liked Y” has become a modern-day aphorism

But ticket sales for events have somehow missed this revolution. Nobody knows whether your attendance at the American Physical Society’s annual meeting in Austin, Texas, last year, means you will enjoy the Comic-con Meeting in London next month.

As a result, this aspect of modern life remains free of (good) recommendations. That’s largely because of the absence of data that allows scientists to find correlations that predict event attendance. While Amazon and Netflix are brimming with data about who bought what when, similarly useful data sets just haven’t been available for events

Until now. Today, Petko Georgiev and pals at the University of Cambridge in the U.K. use data from the location-based social media network Foursquare to tease apart exactly what makes us more likely to attend one event rather than another

It turns out that there are numerous important factors. But these guys say that when the most important are all taken into account, they can predict the events that people will actually go to with remarkable accuracy

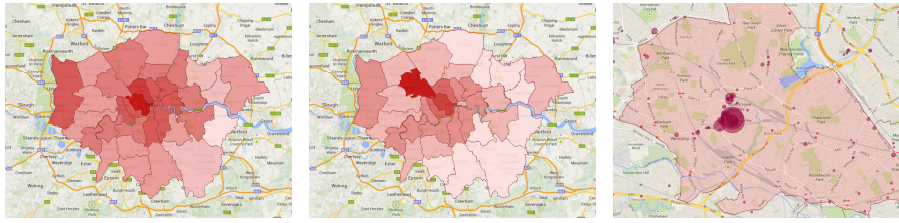

To get their insight, Georgiev and co gathered Foursquare data on the movements of some 190,000 people in London, New York, and Chicago during an eight-month period in 2010 and 2011. Crucially, the social network also revealed networks of friends, a home location and of course the date and times of the movements

Georgiev then mined the data first to find events, which they defined as large gatherings of people and to look up the locations and categorize the events accordingly, whether music festivals, sporting events, or conferences, for example. They also calculated the social attraction of events by counting the number of friends who turn up at the same places.

The question, of course, is how these factors correlate with whether an individual actually turns up for an event. To find out, Georgiev and co used 90 percent of the data as a training set to learn from and then used the remaining 10 percent as a test data set to see whether the correlations they discovered could actually predict attendance

The results provide an interesting insight into human behavior. It turns out that the major influence on attendance is whether friends are also there. That makes sense—most large gatherings are social events of one kind or another

But there are other less obvious but important indicators. For example, distance from home is an important factor—people usually travel only a limited distance to get to an event. The time people are active is also influential. If you tend to be most active in the early evening, then you are more likely to attend early evening events

And your previous pattern of behavior is significant too. For example, if you have been to many football matches in the past, then you are likely to attend football matches in the future. This kind of niche behavior is particularly strong in London, perhaps because of the tribal nature of soccer support

But while all of these factors are influential, the key is in combining them effectively in an algorithm that captures overall behavior. Georgiev and co say they’re done just that

In testing their algorithm’s predictive power on the 10 percent of the data reserved for this purpose, the results were impressive. “Overall, the prediction framework successfully identifies the exact attended event for one in three users in London and one in five users in New York and Chicago,” say Georgiev and co

That’s not bad and raises the prospect of recommendation engines emerging that can accurately predict events that you’d like to attend

There is a caveat, of course, and an important one. This work is based on data published by people who want their location to be known. That’s a self-selecting group whose behavior may be significantly different from those who choose to keep their location private. The event recommendation algorithm may work for them but how well it works for everyone else is an open question

Nevertheless, event recommendation engines look set to become a more prominent part of our online experience, not least because the people who stand to gain most are the event promoters and ticket sellers themselves

The main reason recommendation engines are so common is that they increase sales, sometimes by many percentage points, a feat that is beyond conventional marketing and advertising techniques. If event recommendation engines can be anywhere near as successful, they will flourish too

Ref: http://arxiv.org/abs/1403.7657: The Call of the Crowd: Event Participation in Location-based Social Services

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.