Data Mining Reveals How Conspiracy Theories Emerge on Facebook

During the Italian elections last year, a post appeared on Facebook that rapidly became viral. The post’s title was this: “Italian Senate voted and accepted (257 in favor and 165 abstentions) a law proposed by Senator Cirenga to provide policy makers with €134 billion Euros to find jobs in the event of electoral defeat”.

The post was created on Facebook page known for its satirical content and designed to parody Italian politics. It contains at least four false statements: the senator involved is fictitious, the total number of votes is higher than is possible in Italian politics, the amount of money involved is more than 10% of Italian GDP and the law itself is an invention.

The parody struck a chord with disenchanted voters who shared it some 35,000 times in less than a month. Then things quickly became strange.

The meme was re-posted with additional commentary on a Facebook page devoted to political commentary. The meme then spread all over again but this time with a new veneer of respectability. Today, this “law” is commonly cited as evidence of corruption in Italian politics by protesters in cities all over Italy.

Welcome to the murky world of conspiracy theories. The spread of misinformation over the internet is a celebrated phenomenon. If you believe, for example, that the AIDS virus was created by the US government to control the African American population, then you’re a victim.

Episodes like this raises important questions about how people are exposed to false ideas and how they come to believe them. Today we get an important insight into this question thanks to the work of Walter Quattrociocchi at Northeastern University in Boston and a few pals who have studied the way that ordinary people interact with posts on Facebook that are known to be true or false.

These guys studied how over 1 million people treated political information posted on Facebook during the Italian elections in 2013. In particular, they looked at how these people ‘liked’ posts and commented on them from mainstream news organisations, from alternative news organisation and from pages devoted political commentary.

They then studied how the same people reacted to false news injected into common circulation by “trolls” on pages known to produce satirical news content or otherwise false statements.

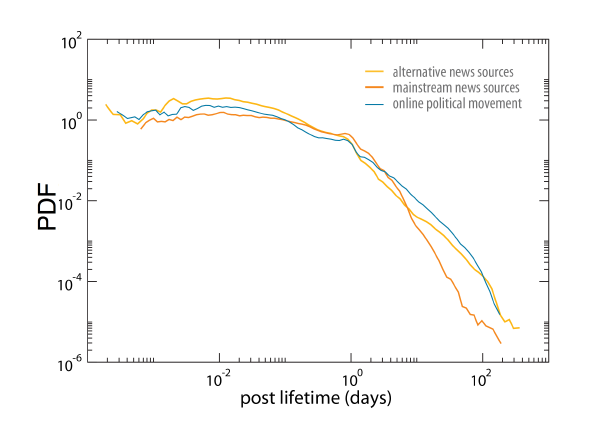

The results make for interesting reading. Quattrociocchi and co analysed how the long the debate about a post continued by measuring the date between the first and last comments about it. They say the length of debate is the same regardless of the type of content.

In other words, people tend to discuss ideas on mainstream news pages, on alternative news pages and on political commentary pages for exactly the same length of time. That suggests the same kind of engagement, regardless of the type of content.

Quattrociocchi and co then studied how the people who engage in these debates also engage in debates on posts that are known to be untrue, like the one about the fictitious law. And they found that some people are more likely to engage with false content than others.

In particular, people who engage with debates on alternative news posts are much more likely to engage in the debate about false news posted by trolls. “We find that a dominant fraction of the users interacting with the troll memes is the one composed of users preeminently interacting with alternative information sources–and thus more exposed to unsubstantiated claims,” they say.

That’s an interesting result. Quattrociocchi and co point out that many people are attracted to alternative news media because of a distrust of conventional news sources, which, in Italy, are strongly influenced by politicians of one persuasion or another.

But this search for other sources of news seems to be fraught with danger. “Surprisingly, consumers of alternative news, which are the users trying to avoid the mainstream media ‘mass-manipulation’, are the most responsive to the injection of false claims,” they conclude.

This suggests an interesting mechanism for the emergence of conspiracy theories. Conspiracy theories seem to come about by a process in which ordinary satirical commentary or obviously false content somehow jumps the credulity barrier. And that seems happen through groups of people who deliberately expose themselves to alternative sources of news.

Of course, there may be other ways that conspiracy theories emerge. Some theories may well be truths that have been deliberately suppressed by higher powers such as governments corporations and so on. But this work reveals that there is also a plausible mechanism through which false stories become thought of as true.

The question now is how to exploit this new understanding to improve the flow and labeling of information, whatever its source.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1403.3344 : Collective Attention In the Age Of (Mis)Information

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.