Are Big, Rich Cities Greener Than Poor Ones?

With more than half of the world’s population now living in cities, there is growing interest in better understanding how these geographical social structures work. Consequently, a new science of cities is being fueled by the sudden availability of fascinating datasets collected from urban areas all over the world.

One of the more curious puzzles emerging from this data is how aspects of urban life change as cities get bigger. For example, the number of houses and jobs in a city grows in proportion to the size of the population. But the number of gas stations scales more slowly. And people’s wages grow faster, so people in big cities earn more than those in small ones.

That raises all kinds of questions about other aspects of city life. A particularly important one is whether big cities are greener than small ones, whether big cities emit more carbon dioxide per capita than small ones.

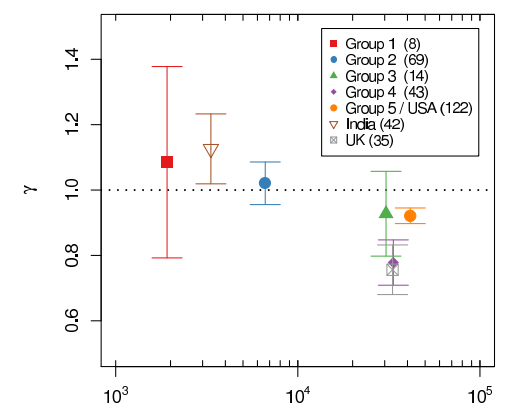

Today, we get an answer of sorts from Diego Rybski at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany and a few pals. These guys give an interesting twist to the debate. They say that big cities in rich countries are greener than small ones but big cities in poor ones are the opposite. And the transition occurs when the GDP per capita climbs above $10,000 per head.

The data crunching behind this is straightforward, at least in principle. These guys analysed the carbon dioxide emissions from 256 cities of various sizes from all over the world. They than worked out the emissions per capita for each and ranked them accordingly.

What they found was something of a surprise. In the developing world, the doubling of city size leads to an increase in carbon dioxide emissions of about 115 per cent. “The results suggest that in developing countries, large cities emit more CO2 per capita compared to small cities,” say Rybski and co.

By comparison, the emissions per head drop as city size grows in the developed world, where a doubling in size typically leads to an increase in emissions of only about 80 per cent.

The results imply that large cities in rich countries are more efficient than those in poor countries. But just why this should be is something of a puzzle. One possibility is that cities in the developed world are more focused on producing services whereas in the developing world, cities have more industry and so produce more carbon dioxode.

The bottom line, according to Rybski and co, is this: “We conclude that urbanization is desirable in developed countries and should be accompanied by efficiency-increasing mechanisms in developing countries.”

There are one or two important caveats. It’s worth noting that the developed world produces significantly more emissions per capita than the developing world. So not everyone would agree with the idea that the developing world should aspire to imitate the developed world in this respect.

A more serious problem is the nature of the data. It is notoriously difficult to define the size of a city either geographically or population-wise. So an important question mark over this study is whether the data from different places is really comparable.

Only last month, for example, we reported on a study claiming to have found that big cities in the US produce more carbon dioxide per capita than small ones. That directly contradicts the findings here.

Perhaps the inconvenient truth here is that until we can find better ways to define cities and measure their carbon dioxide output, it’s going to be difficult to draw any conclusions about whether big cities are better for the planet than small ones.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1304.4406 : Cities As Nuclei Of Sustainability?

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.