Virtual Reality Startups Look Back to the Future

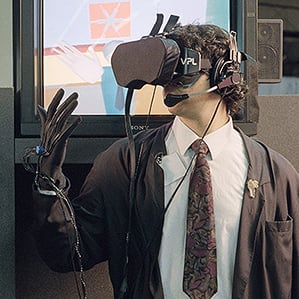

It’s been almost 30 years since the computer scientist Jaron Lanier formed VPL Research, the first company to sell the high-tech goggles and gloves that once defined humanity’s concept of where technology might soon take our species. In the late 1980s, people could pull on a $100,000 head-mounted display and electronic gauntlet and fool their brains into thinking they’d stepped inside the simulated space rendered on the screen.

At the time, Lanier’s intoxicating inventions were featured on the front page of the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times, coverage that popularized the term “virtual reality” as well as a fresh vision of the future in which humans would flit between the real and virtual worlds. The well-worn narrative is that the VR pipe dream quickly faded, largely due to the exorbitant costs involved or the motion sickness that many users complained of when playing early consumer examples of the technology—such as Nintendo’s ambitious and experimental Virtual Boy games console controller.

Now, after many years on the periphery, VR is heading back to the mainstream. The proliferation of cheap high-resolution screens, motion-tracking sensors, and microchips in mobile computing devices has vastly reduced the technological cost of creating virtual reality hardware, making high-definition immersive head-mounted displays commercially viable.

The most prominent startup riding the renewed interest in virtual reality is Oculus VR, a company that has released a developer kit costing just $300, a fraction of the price of the emergent units of the 1980s (the consumer version is rumored to cost even less). The Oculus Rift retail kit will boast higher resolution than the developer versions when it launches in late 2014—1920 x 1080 pixels compared to 640 x 800 pixels—a technological accomplishment that has only recently become commercially viable. Palmer Luckey, the 21-year-old inventor of Oculus Rift (and who has raised millions of dollars in investment capital in the past year), believes VR is ready for the mass market (see “Can Oculus Rift Turn Virtual Wonder into Commercial Reality?”).

Lanier, however, rejects the idea that this is some kind of resurgence. He argues that VR has already revolutionized the world. “You can’t enter a vehicle made in the past 20 years that wasn’t first prototyped in VR,” he says. “As a result we’ve seen vehicles become safer, more comfortable, and more efficient, and VR has played a key role in that. Likewise, you can’t have an operation without the surgeon having benefited from VR.”

What’s new is the prospect of a mainstream, affordable consumer VR device, but even here Lanier insists that the current batch of hopeful startups are more or less redoing what he and his partners did three decades ago. “There are so many details that are similar,” he says. “I’m happy to see these companies doing what they’re doing and am charmed by it.”

Lanier may be charmed, but he’s unconvinced that the positive rhetoric surrounding the current VR makers will have an effect in the marketplace. It’s certainly true that Oculus Rift got off the ground thanks to the fervor of a core group of supporters who contributed to Luckey’s initial Kickstarter campaign. The project page says that more than 9,000 people pledged a total of nearly $2.5 million.

“There’s an extremely intense enthusiast community that loves VR,” Lanier says. “But it can create an illusion that interest is perhaps larger than it really is. I believe Oculus Rift could launch tomorrow and comfortably sell a few hundred thousand units. But the real challenge is how to sell 200 million units. The enthusiast community is loud and adorable, but no matter how much you please them, you won’t necessarily reach beyond them.”

Luckey is, understandably, a great deal more positive. “People have wanted virtual reality for decades,” he says. “There is a reason it has been core to so much great science fiction storytelling. Unfortunately, the tech was just not ready in the past.”

Luckey insists that today, the various necessary ingredients are available and affordable: high-powered miniature computing, highly detailed 3-D synthetic environments, high resolution screens, and high-precision motion tracking. “All of these things are available relatively cheaply,” he says.

The result of this technological convergence is certainly arresting. People often talk of a unique feeling of “presence” when using the Oculus Rift for the first time, the latest iteration of which debuted at the Consumer Electronics Show in January. It’s unlike a traditional video game. In a VR world, the combination of actual scale and one-to-one head tracking—whereby natural head movements are used to observe the virtual world—contribute to a new sense of being present in the simulated world. The technology overwhelms the human perceptual system so that it has trouble differentiating immersive virtual experiences from real ones.

Lanier, who worked with Microsoft on its Kinect motion cameras, agrees that the technology is far cheaper today, but he can perceive few “profound differences” to ease the difficulties he and his team experienced in the 1980s. “All of the current [head-mounted display] makers face the same challenges that we did in 1985,” he says. “It’s relatively straightforward to create a great demo and unbelievably hard to do a great product.” Lanier also predicts a sense of user ennui after the initial wonder fades. “I found in the old days that looking into a virtual world becomes a little tiring at some point,” he says. “It’s a little like Google Glass, where the notion that this technology is on your head all the time is too much and people start to reject it. Your first time playing a game in a virtual world is incredible, but the 20th time is wearying. The gaming modality is self-limiting. I’m not saying there’s anything wrong with it, but you can’t limit your strategic thinking to that one style of use.”

As Lanier suggests, a range of software may be key to illustrating the potential of virtual reality.

“A lot of things have come together simultaneously to make this year ripe for VR to finally take off,” says Devin Reimer, chief technology officer of Owlchemy Labs, an independent game studio based in Boston that is working on a base-jumping game for Oculus Rift. “The mobile-display resolution race has forced the cost of high pixel density displays down. The availability of cheap and small accelerometers, magnetometers, gyroscopes, and compasses also contributes to this effect. With compact CPUs and GPUs able to render two high-resolutions views at high frame rate, the tech really is there.”

Alex Schwartz, CEO of Owlchemy Labs, says the potential isn’t limited to video games. “We’ve been thinking about school field trips,” he says. “Their purpose is to allow students to experience the world about which they’ve only learned from their teachers and textbooks. When a child can experience the grandeur of a Tyrannosaurus rex skeleton for the first time at a science museum, it’s unlike anything else. Pictures can’t describe the sense of scale felt when seeing a full-size dinosaur skeleton in the flesh, but VR is able to replicate that sense of scale to allow for these amazing experiences in the classroom, especially when visiting a physical location is impossible.”

Some academics already see broad potential uses for virtual reality. Jeremy Bailenson is founding director of Stanford University’s Virtual Human Interaction Lab, where he performs numerous experiments to understand both the potential uses and effects of VR. Bailenson’s lab is focused on exploring how VR can be used to encourage prosocial behavior, teaching empathy, encouraging helpful behaviors, and deterring environmental degradation. “One recent study demonstrated that an intense and altruistic VR experience such as flying around like a superhero to save a child’s life caused people to be more helpful in the physical world towards someone that had an accident. Another demonstrated that allowing someone to walk a mile in another person’s shoes, for example by using the technology to simulate a visual disability, caused people to increase the amount of time they spent volunteering to help others who are visually impaired.”

But Bailenson also views VR’s power to engage and persuade as a potential downside. “I think of VR like uranium,” he says. “It can heat homes and destroy cities. One can easily point to the addictive aspects of the technology as a downside. The question is, how will we use it?”

“In fiction, VR is often portrayed as the final great technology, something that leads the world into a dark, dystopian future,” says Oculus Rift inventor Luckey. “In reality, the benefits of VR will far outweigh the negatives; education can be vastly improved, long distance collaboration will be revolutionized, and firefighter, police, and military training can be done much more safely and cost effectively.”

Lanier, the father of VR, is more equivocal about the moral, ethical, and political future of VR. “The tech itself lends itself to a wide variety of different frameworks,” he says. “If it’s used as a spying tool or a way to make advertising work more effectively, then it will gradually hurt people. But if it’s used as a way to help people know themselves more, and if the person is the power center rather than the remote company, then it will aid education and can be joyous and beautiful.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.