The Tricky Problem Of Making Smart Fridges Smart

The 1990s dream of an internet-connected fridge has been much derided in the last decade or so. Even the most advanced smart fridges are little more than a conventional fridge with a few added gimmicks such as a barcode scanner or a tablet screen attached to the front. Consequently, smart fridges have been anything but and the public has responded with little, if any, interest.

But Thomas Sandholm and pals from the Korean Advanced Institute of Technology in Daejeon, South Korea, hope to change that. These guys have developed a system called CloudFridge that hopes to fix everything that’s wrong with smart fridges, thereby returning them to their rightful position in the pantheon of consumer technology breakthroughs.

When they were first conceived in the 1990s, smart fridges promised to revolutionise the way we interact with food. The dream was that these devices would monitor everything we put into and take out of the fridge, warned us when items were running low or close to their use by dates and even ordered replacements.

But this dream has never materialised. The main problem, says Sandholm and co, is that smart fridges require too much input from the person using them. For example, many require the user to scan food items using a bar code scanner when they take them in and out of the fridge.

And they have other failings too. One system had an RFID scanner to track food usage, only to be foiled by the fact that few if any food items have RFID tags. Another measured how often the fridge was opened and closed to monitor usage patterns. It was also equipped with a proximity sensor to detect whether anything was taken out of or put into the fridge. But it failed because it had no way of telling what was being taken.

The long and short of it is that the history of smart fridges is a story of technology trampling over convenience and utility.

Sandholm and co think they can change that with a prototype system designed to study and improving the user experience. “Our main claim… is that a testbed geared towards evaluating realistic user experiences could be the catalyst for innovations in the field.”

To this end, they have created a fridge with three significant advances over previous designs. The first is an object recognition system that may actually work without the user doing anything other than taking items in and out of the fridge.

The trick is to enlist the help of Google. Sandholm and co’s fridge is fitted with a webcam that photographs each item as it is put into or taken out of the fridge and sends the resulting image to Googles’ Search By Image service.

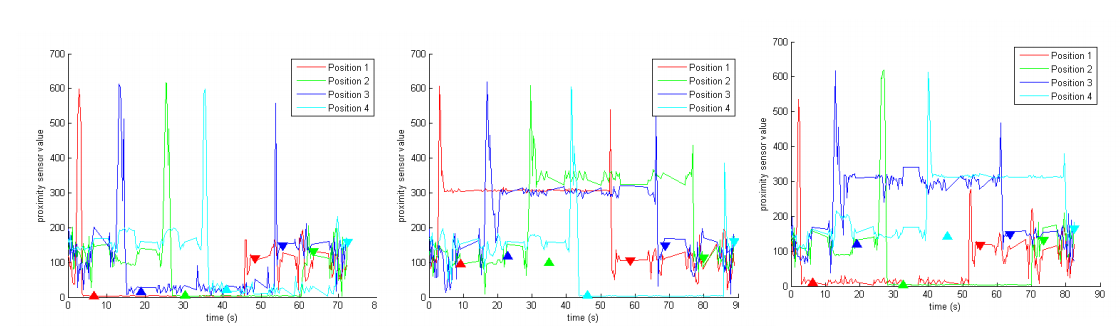

The second is a system that accurately measures the position of objects placed in the fridge using infrared sensors.

The final advance is a set of red or green LEDs that can spotlight objects in the fridge to bring them to the user’s attention, perhaps because they need replacing or are close to their ‘use by’ dates. The resulting prototype has the potential to significantly outperform earlier smart fridges.

Sandholm and co have developed a number of apps that work with the new prototype. One known as CloudFridge Take Out makes it easier to find items you’ve placed in the fridge by saying their name. The fridge then spotlights that object. Sandholm and co say it could be made to highlight all the items in a particular recipe, for example, ensuring that you’ve used all the appropriate ingredients.

“We are also planning on adding social features to share your fridge content with friends or compare tastes to be able to get collaborative-filtering-based and social recommendations,” they say.

All very well but the big problem of course is object recognition. Even Google’s Search By Image service takes up to 5 seconds to analyse a single image and return a result. Even then, it doesn’t always recognise it or simply matches it to the same image in its database without giving it a name.

That’s reflected in the results of Sandholm and co’s tests, where the accuracy of the object recognition is the limiting factor in the utility of their new prototype.

Object recognition is something that will improve in the coming years. Sandholm and co are clearly taking a step in the right direction but truly smart fridges might still be just beyond our ken.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1401.0585: CloudFridge: A Testbed for Smart Fridge Interactions

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.