Nanoparticle That Mimics Red Blood Cell Shows Promise as Vaccine for Bacterial Infections

A nanoparticle wrapped in material taken from the membranes of red blood cells could become the basis for vaccines against a range of infectious bacteria, including MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus), an infection that kills tens of thousands of people every year.

Researchers at the University of California, San Diego, have shown that the nanoparticles, loaded with a common bacterial toxin and injected into mice, can induce an immune response that protects the animals against a subsequent lethal dose of the toxin. The toxins, which are proteins the bacteria secrete, are “pore-forming,” meaning they target cell membranes in the host and poke severely damaging holes in them. The proteins are secreted by many bacteria in addition to Staphylococcus aureus, including clostridium, listeria, strep, E. coli, and a range of other infectious bugs.

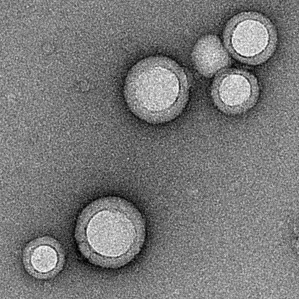

Liangfang Zhang, a professor of nanoengineering at the University of California, San Diego, had previously injected nanoparticles wrapped in membranes taken from red blood cells into mice that had been given large doses of toxin. The toxins targeted the decoy red blood cells; instead of forming deadly pores in real cells, they got themselves trapped and neutralized by Zhang’s “nanosponges,” which were then cleared from the body. (See “Nanoparticle Disguised as Red Blood Cell Fights Bacterial Infection.”)

The nanosponges are so small that the membrane of a single red blood cell can supply enough material for 3,000 of them. According to Zhang, they can vastly outnumber the real red blood cells and divert toxins away from their natural targets, soaking up toxins from blood. Removing the toxin makes the bacteria more vulnerable to the immune system.

Now, Zhang has demonstrated that this same technology could be used to build vaccines similar to the “toxoid” vaccines used to inoculate people against diphtheria and tetanus. Whereas some bacterial vaccines work by inducing an immune response against the microbe itself (or parts of it), toxoid vaccines target bacterial toxins.

In experiments, Zhang and colleagues loaded alpha toxin, a type of pore-forming toxin produced by MRSA, into their nanosponges and injected them into mice. The “nanotoxoid” proved nontoxic and induced the production of antibodies that gave the animals protective immunity against the toxin. It also significantly outperformed an experimental vaccine made from a heat-treated form of the same toxin. The research is described in a recent paper in Nature Nanotechnology.

Whether a toxoid vaccine will work depends on the bacteria. Many bugs have other disease-causing factors in addition to their toxins. Staphylococcus aureus, for example, secretes the pore-forming toxin Zhang’s group used in its vaccine, but it also has proteins on its surface that bind to and disable crucial immune cells. After decades of research and many failed clinical trials, it’s still not clear which targets, or combination of targets, a vaccine must attack to be successful. Currently, some large pharmaceutical companies are pursuing multitarget MRSA vaccines.

Making a new vaccine is a complicated process that can take over 10 years. Victor Nizet, a professor of pediatrics and pharmacy at UCSD, is now collaborating with Zhang to test the nanotoxoid vaccines in mice infected with various forms MRSA. Since Staphylococcus aureus secretes several different pore-forming toxins, it should be possible to load several toxins at once into the nanoparticle, says Nizet, and “potentially have more robust protection against multiple strains.”

Zhang’s nanotoxoid also has the potential to lead to vaccines for multiple other bacterial species that rely on pore-forming toxins to harm their hosts.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.