Drone Gets Its Smarts from a Smartphone

Researchers are using a smartphone as the brains behind a small, inexpensive drone—the phone enables it to find its way around enclosed indoor spaces without using GPS or a remote guide. Although it’s still at an early stage, the so-called SmartCopter could eventually make it safer and cheaper to scout out disaster scenes before human responders plunge in.

Annette Mossel, a graduate student behind the project who studies virtual reality, tracking, and 3-D interaction at the Vienna University of Technology, says the idea was born out of a desire to create an inexpensive, autonomous, unmanned aerial vehicle that could help survey disaster scenes. Using a smartphone as the processing unit cuts costs and makes it easier to update the drone’s software, she says.

Several robots have been developed that can crawl inside buildings or check out suspicious packages, including bots that can be thrown, such as iRobot’s FirstLook robot and Bounce Imaging’s camera-laden ball, called the Explorer (see “Bouncing Camera Gets into Dangerous Places So People Don’t Have To”).

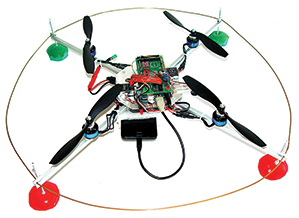

The SmartCopter could be less expensive than these devices. The Vienna group built its test drone using four motors, an Arduino microcontroller, and a Samsung Galaxy S II Android smartphone. Excluding the phone, Mossel says, the drone cost about 300 euros ($412) to build. “We wanted to keep the costs low and build our copter based on open hardware approaches,” Mossel says. A paper on the SmartCopter was presented this month at the International Conference on Advances in Mobile Computing & Multimedia in Vienna, Austria.

The big challenge was figuring out the best approach to navigating without using the phone’s built-in GPS, since the technology doesn’t work well (if at all) indoors, and may not be precise enough in some situations (the U.S. government website devoted to GPS indicates that the technology is accurate to within about 26 feet).

The group’s first prototype solved this challenge in a fairly low-tech way: by detecting paper markers that had been set up in the area the drone needed to track. An app on the smartphone tells the drone to lift itself to a predetermined height, from which it starts looking for the markers. Each time it finds a new marker, it is added to the drone’s map. By looking at the markers and evaluating different sensory input from the smartphone’s accelerometer, gyroscope, and magnetometer, the software can determine the drone’s position in space, Mossel says.

Once the drone stops finding new markers, it simply hovers and waits for new instructions from a remote laptop that monitors its flight. It could also be programmed to land in a specific spot (perhaps its starting point outside a building, for example) once its job is done.

Besides scoping out disaster scenes, Mossel can imagine a slew of other uses for the SmartCopter, from inspecting the condition of walls and ceilings in big, open rooms in churches and museums to helping shoppers navigate malls.

Among the obstacles the SmartCopter team will encounter if it forges ahead with developing an actual product is a regulatory climate that hasn’t figured out how to deal with drones. The U.S. Federal Aviation Administration has not set rules for drone safety and operation, but those regulations are in the works and are expected to go into effect in 2015.

For now, Mossel and her colleagues are focused on the next phase of their research, which involves getting the smartphone to track features of a room like corners and gradients so the drone doesn’t need to use markers to map its surroundings.

“We don’t think, ‘Okay, in a year we will make a company and turn it into a product,’ ” she says. “But I think it’s pretty possible for all of us who are working on it.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.