Google Tries to Turbocharge Internet Service in Uganda

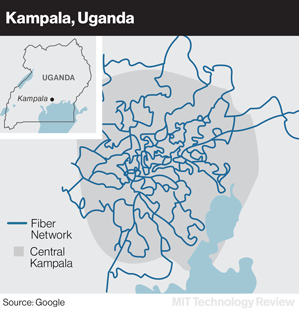

Google is making one of its biggest moves yet into the business of providing Internet infrastructure, installing a fiber-optic backbone to dramatically improve connectivity in Kampala, Uganda.

The calculus is simple for Google: the more that people do online, the better its core business of selling Internet ads can be. That’s why the company has been stringing fiber-optic connections to homes in Kansas City and other U.S. cities and has toyed with the idea of launching fleets of balloons or blimps that could beam wireless Internet access down to rural areas throughout the world.

The new network for Kampala—installed in recent months but announced Wednesday—will enable as many as 10 mobile carriers and Internet service providers to boost data rates by a factor of 100 in most areas of the city, which has three million residents. The backbone connects cellular towers to new fiber lines that are, in turn, connected to larger fiber networks and undersea cables.

Most of the fast access—up to two gigabits per second in some cases—is intended for mobile devices, but ISPs could also extend the fiber network directly into institutions like hospitals and universities, says Kai Wulff, access field director for the Google effort, called Project Link. “Our goal is to connect more people in Kampala to fast, quality Internet,” he says. He would not say how much money the fiber project cost the company.

Whatever Google’s motives, the effort should lead to better service, lower prices, and economic benefits for Ugandans, says Erik Hersman, director of iHub, a startup incubator in Nairobi, Kenya. Google’s strategy “seems to be to sell wholesale to the ISPs in Uganda for a lot less than they currently pay, hoping to spur a race to the bottom on data prices,” he says. “If they’re able to engineer a reduction in prices, that’s huge.”

Indeed, lowering the cost will be vital for expanding Internet access to places that don’t have it. About 2.7 billion of the world’s seven billion people can get online; the rate is lowest in Africa, where 16 percent of its one billion residents have Internet connections of some kind. The U.N. Broadband Commission says that for Internet use to increase in Africa, prices would have to be under $5 per month.

Wulff declined to predict the final prices that end users might pay in Kampala, since those fees will be determined by carriers and ISPs that will pay Google to use its backbone. Three of the region’s 10 service providers have already signed agreements to use it.

Wulff says Google has no immediate plans to wire up other cities. For now, Google is focused on proving the business model in Kampala and encouraging other infrastructure providers to follow suit.

A bigger challenge will be to bring the Internet to areas that lack any Internet connectivity at all. Many technology companies, including Google and Microsoft, are experimenting with using television frequencies to extend broadband access to such far-flung areas. And Facebook recently announced an industry coalition called Internet.org that’s geared toward expanding Internet access, with an initial focus on improving the efficiency of data transmission in areas that already have connectivity.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.