Twitter Datastream Used to Predict Flu Outbreaks

Back in 2008, Google launched its now famous flu trends website. It works on the hypothesis that people make more flu-related search queries when they are suffering from the illness than when they are healthy. So counting the number of flu-related search queries in a given country gives a good indication of how the virus is spreading.

The predictions are pretty good. The data generally closely matches that produced by government organisations such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the US. Indeed, in some cases, it has been able to spot an incipient epidemic more than a week before the CDC.

That’s been hugely important. An early indication that the disease is spreading in a population gives governments a welcome headstart in planning its response.

So an interesting question is whether other online services, in particular social media, can make similar or even better predictions. Today, we have an answer thanks to the work of Jiwei Li at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, and Claire Cardie at Cornell University in New York State, who have been able to detect the early stages of an influenza outbreak using Twitter.

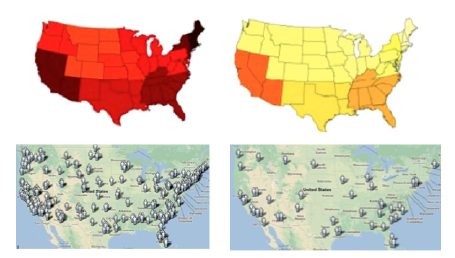

Their approach is in many ways similar to Google’s. They simply filter the Twitter datastream for flu-related tweets that are also geotagged. That allows them to create a map showing the distribution of these tweets and how it varies over time.

They also model the dynamics of the disease with some interesting subtleties. In the new model, a flu epidemic can be in one of four phases: non-epidemic phase, a rising phase where numbers are increasing, a stationary phase and a declining phase where numbers are falling.

The new approach uses an algorithm that attempts to spot the switch from one phase to another as early as possible. Indeed, Li and Cardie test the effectiveness of their approach using a Twitter dataset of 3.6 million flu-related tweets from about 1 million people in the US between June 2008 and June 2010.

To check how well their predictions work, Li and Cardie compared their analysis to that produced by the CDC. “We verify that flu-related tweets are highly correlated to the number of influenza-like illness (ILI) cases provided by CDC,” they say.

That looks to be a powerful and important new tool in the battle against influenza epidemics. It certainly provides a new way to spot the disease in its early stages. Indeed, an interesting task will be to compare its effectiveness against other systems such as Google’s flu trends and the CDCs own predictions.

Some 10-15% of people get flu each year which results in around 50 million cases and 500,000 deaths around the world. That’s a heavy toll. The ability to spot the start of an epidemic a week or so earlier than is possible now, and doing it relatively cheaply and easily all over the world, could allow governments and medical agencies to save a significant number of lives.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1309.7340: Early Stage Influenza Detection from Twitter

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.