Rich-Get-Richer Effect Observed in BitCoin Digital Currency Network

In January 2009, a small group of Internet enthusiasts began an unusual economic experiment when they began to trade a new type of digital cash known as BitCoin. After a shaky start, the idea caught on and grew rapidly after 2011.

Today, bitcoins can buy a wider range of goods and services. In total, the BitCoin marketplace has hosted over 17 million transactions and the value of all the bitcoins in circulation is over $1 billion.

One interesting aspect of this marketplace is that the complete list of all transactions is publicly available. And this gave Daniel Kondor and buddies at Eotvos Lorand University in Hungary an idea.

These guys have downloaded this complete list of transactions and reconstructed the entire financial history of each account in the market. Using this data, they have recreated the flow of digital cash through the network and studied the resulting patterns of wealth creation and accumulation.

“We believe that this is the first opportunity to investigate the movement of currency in such detail,” they say.

Kondor and pals recreated the network so that each node represents a BitCoin address and drew a link between two nodes if there was at least one transaction between them. They then analysed the way the network has evolved over time.

Kondor and co say that the evolution clearly occurred in two separate phases. Before 2011, the system was used only by a few enthusiasts and the bitcoins had no real-world value. During this time, there was little activity and the various measures of network structure varied hugely.

In 2011, however, BitCoin began to get significant media coverage which attracted many more users. The currency also became more attractive after an exchange was set up that allowed bitcoins to be traded for dollars. During this second phase, bitcoins started to function as a real currency.

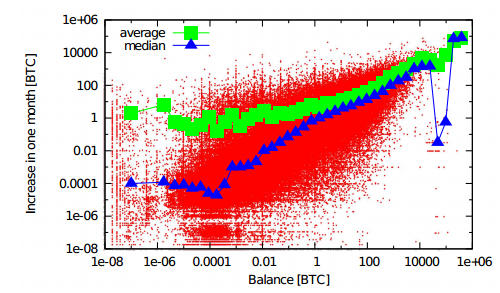

The team’s key finding from this second phase is related to wealth accumulation. Kondor and co say that the network grew by preferential attachment. In other words, a node with a large number of links is likely to attract more links than a node with only a few links.

This is a well-known effect in network science. Economists call it the Matthew effect after the biblical observation that the rich get richer.

Examples of the Matthew effect occur in many networks. Popular websites are likely to grow more rapidly than less popular ones, for example. And a similar process is thought to occur in real economies where the rich really do seem to get richer.

The Matthew effect is thought to be the origin of the 80:20 distribution of wealth– that 20 per cent of the population own 80 per cent of the wealth.

Kondor and co say a similar phenomenon is clearly observable in the BitCoin network. Not only are popular nodes likely to attract more links, their wealth is also likely to grow more quickly than less popular nodes. “The ability to attract new connections and to gain wealth is fundamentally related,” they say. “The “rich get richer” phenomenon is indeed present in the system.”

An interesting aspect of this currency is that the transactions are largely anonymous. As a result, the buying and selling of illegal goods and services is probably overrepresented in the network. If so, the Matthew effect must be at work even in this shadowy world.

This kind of approach has significant potential for future studies. Kondor and co say the transparency of the network means that this system could be hugely valuable for econophysicists wishing to evaluate and refine their models. In no other system of currency is it possible to study what goes on in such detail.

Could bitcoins eventually replace ordinary cash? Kondor and co avoid making any predictions, but the evidence they have unearthed is that the BitCoin network already functions in a way that is uncannily similar to real world currencies. So in that respect, there is nothing to stop it being more widely adopted.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1308.3892 : Do The Rich Get Richer? An Empirical Analysis Of The Bitcoin Transaction Network

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.