An Inexpensive Fuel-Cell Generator

People could soon get cleaner energy from a compact fuel-cell generator in their backyards, at costs cheaper than power from the grid. At least, that’s the hope of Redox Power Systems, a startup based in Fulton, Maryland, which plans to offer a substantially cheaper fuel cell next year.

Redox is developing fuel cells that feed on natural gas, propane, or diesel. The cells, which generate electricity through electrochemical reactions rather than combustion, could allow businesses to continue operating through power outages like those caused by massive storms such as Hurricane Sandy, but they promise to be far cleaner and quieter than diesel generators. They can also provide continuous power, not just emergency backup power, so utilities could use them as distributed power sources that ease congestion on the grid, preventing blackouts and lowering the overall cost of electricity.

Redox’s claims sound a lot like those made in 2010 by Bloom Energy (see “Bloom Reveals New Fuel Cells”), a well-funded fuel-cell startup in Sunnyvale, California. But Bloom’s fuel cells are based on relatively conventional technology, and so far they have proved far too expensive for homes. Redox claims to have developed fuel cells based on novel materials that could cut costs by nearly 90 percent. The first product will be a 25-kilowatt generator that Redox says produces enough electricity for a grocery store. The company eventually plans to sell smaller versions for homes.

Redox’s fuel cells are based on highly conductive materials developed at the University of Maryland that help increase power output by a factor of 10 at lower temperatures (see “Gasoline Fuel Cell Would Boost Electric Car Range”). The company says its fuel cells will pay for themselves with electricity-bill savings in two years.

Redox, a self-funded company founded just two years ago, is basing its cost estimates on data derived from manufacturing key components of the fuel-cell systems. But it hasn’t started making complete systems, which would include several stacks of the fuel cells and other equipment such as pipes and pumps for distributing fuel to them.

The type of fuel cell Redox makes is called a solid-oxide fuel cell. Like all fuel cells, it produces power through electrochemical reactions. Unlike those being developed for use in cars, it can run on a variety of fuels, not just hydrogen. Redox’s cells will release carbon dioxide, but emissions per kilowatt-hour should be lower than those associated with power from the grid.

Though Bloom also uses solid-oxide fuel cells, Redox’s are more advanced, says Mark Williams, a former technical director for fuel cells at the U.S. Department of Energy, who is not connected to Redox. He says they’re among the most powerful solid-oxide fuel cells ever made, producing about two watts per square centimeter versus 0.2 watts for Bloom’s cells.

Warren Citrin, the company’s CEO, says the fuel-cell systems will cost about $1,000 per kilowatt, compared with $8,000 per kilowatt for Bloom. However, the company’s claim of a two-year payback is a rough estimate; it doesn’t include the cost of financing, for example, and it factors in expected economies of scale from producing about 400 fuel-cell systems per year, although the company has yet to manufacture even one complete system so far.

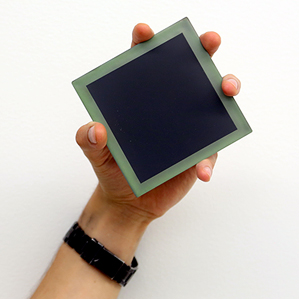

Citrin says the company has made the individual ceramic plates that fit inside the fuel-cell system. It started with small, experimental “button” fuel cells from the University of Maryland and, working with contract manufacturers, demonstrated that it’s possible to manufacture the larger, 10-centimeter-wide versions needed in a commercial system. It’s also started testing stacks of these cells.

Citrin says the company plans to finish a 25-kilowatt prototype by the end of the year, in time to start selling complete systems by the end of 2014.

Because Redox hasn’t yet manufactured complete systems, it remains to be seen how reliable they will be. Fuel cells are notorious for requiring expensive maintenance and not lasting more than a few years, which is one of the reasons they haven’t taken off yet.

Eric Wachsman, director of the University of Maryland Energy Research Center, who developed the original technology, believes the system will perform well over time because it operates at lower temperatures than other versions, reducing damage to the fuel cells. He says data from individual cells suggest that the systems could last for 10 years—still far short of the lifetime of a power plant, but within the payback period.

Deep Dive

Climate change and energy

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Harvard has halted its long-planned atmospheric geoengineering experiment

The decision follows years of controversy and the departure of one of the program’s key researchers.

Why hydrogen is losing the race to power cleaner cars

Batteries are dominating zero-emissions vehicles, and the fuel has better uses elsewhere.

Decarbonizing production of energy is a quick win

Clean technologies, including carbon management platforms, enable the global energy industry to play a crucial role in the transition to net zero.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.