A Novel Way to Cut the Cost of Advanced Biofuels

A novel genetic modification to plants could make advanced biofuels more competitive with fossil fuels, according to a study published this week in the journal Science. The modification could achieve this by rendering an expensive step in making such biofuels unnecessary.

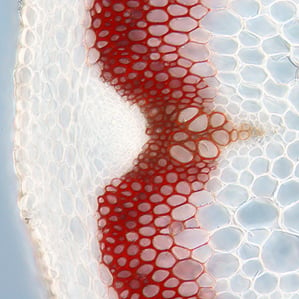

Currently almost all ethanol production comes from the sugar and starch in sugarcane and corn grain. Producing biofuels from biomass remains too expensive to be competitive, partly because the current method for freeing up the cellulose from lignin, the substance that gives plants woody properties, is to treat biomass with hot acid. This step is expensive in part because it requires specialized equipment that can withstand the acid.

In the new work, researchers discovered that when they eliminated a key gene responsible for how lignin is formed, plants produced far less of the substance. They then showed that 80 percent of the cellulose in these modified plants could be converted to sugar without treating them with acid. In comparison, in untreated, ordinary plants, only 18 percent of the cellulose could be converted.

The work is still far from commercial application. The researchers have yet to show that the approach works with the kind of plants that will be used for making biofuels, such as switchgrass or poplar, but they’ve found similar lignin-producing steps in these plants, suggesting that it will be possible to transfer the approach.

Another challenge is that the genetic modification produces shorter plants with less biomass, which would lead to lower biofuel yields. The problem is that lignin is a crucial structural material, and decreasing it too much affects the way plants grow. But researchers at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory recently demonstrated a way to reduce lignin content in some parts of the plant, but not others, thereby allowing the plant to grow normally. Woet Boerjan, a professor at VIB, a research institute in Belgium, and one of the researchers involved in the new work, says a similar approach could work in their case.

Meanwhile, companies have been developing their own ways around the acid treatment. Ceres, based in Thousand Oaks, California, says it has modified plants, including reducing lignin content. It’s tested the approach in labs, and is now growing crops that it will harvest and test this fall. Richard Hamilton, Ceres’s CEO, says eliminating the acid pre-treatment could reduce the amount of enzymes needed to convert cellulose into sugar, and could cut as much as $1 per gallon from the cost of making ethanol from biomass, a large reduction for an industry that hopes to reach costs of $3 to $4 per gallon.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.