Internet Congestion Trouble-Spots Revealed

Every internet user has had the frustrating experience of staring at streaming video while it buffers or waiting for a webpage to load. These problems are the result of internet congestion where packets of data cannot be rooted quickly enough to meet demand.

Just as frustrating is the inability to work out what is causing this congestion. Internet users are generally left scratching their heads when it comes to working out which part of the network is responsible for the snarl up.

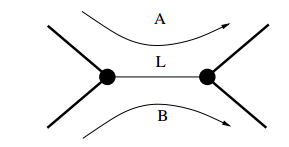

An interesting question for most users is where the congestion actually occurs. There is a common belief that most congestion occurs in the so-called “last mile”, the final part of the network that links the home or place of work to the network. But is that true?

Other possibilities are that the congestion occurs in the so-called “middle mile”, the network run by the local Internet service provider (ISP) or further afield such as where the ISP connects to the public Internet or even somewhere else entirely.

And there are other questions too. For example, does the pattern of congestion change over time?

These puzzles are not easy to answer largely because the private companies that own various parts of the network keep the details about their traffic, capacity and network topology secret.

And yet, this strategy of secrecy does not serve internet users well and is almost certainly not in the best interests of the ISPs either. “Even the ISPs would benefit from [a better understanding of congestion] as it would allow them to target infrastructure improvements at the key points in the network where return on investment, in terms of enhanced user experience, would be greatest,” say Daniel Genin and Jolene Splett at the National Institute of Standards and Technology in Gaithersburg, Maryland.

That’s partly why in 2010 the Federal Communications Commission began a long term project to gather data about internet congestion and to find out where it really occurs. This study, carried out by a private company called SamKnows, has involved over 10,000 measurement units deployed at the homes and work places of customers of 16 ISPs in the US.

These units–Netgear routers with special firmware–send data to certain servers which measure the time the data takes to get there; the units also download pages from major websites to see how quickly they load. By analysing the results of these tests over long periods of time and from many units, it’s possible to build up a picture of where the congestion occurs and how it changes.

Although the project is ongoing, the data gathered so far is publicly available and today, Genin and Splett reveal its first results. They say that congestion on ISPs offering DSL broadband follows an entirely different pattern to the congestion associated with ISPs offering cable broadband.

It’s worth pointing out that cable broadband is generally much faster than DSL. But do you get the advertised speed?

Not according to Genin and Splett. They say that DSL broadband connections general give download speeds that are at least above 80% of the advertised speed more than 80% of the time. “By contrast, a significant fraction of cable connections received less than 80% of their assigned speed tier more than 20% of the time,” they say.

What’s more, the problems don’t appear to be in the last mile and instead occur deeper into the network. “This is somewhat contrary to the popular belief that the edge is more congested than the core,” say Genin and Splett.

There’s still significantly more work to be done to determine exactly what causes this kind of congestion and where exactly it happens and we should see the results of this analysis in the coming months and year.

In the meantime, the results from Genin and Splett should give ISPs something to think about. At the very least, they might want to consider making their traffic data public so that everyone, including the ISP’s themselves, can benefit from the greater insight this should produce.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1307.3696 : Where In The Internet Is Congestion?

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.