A Battery and a “Bionic” Ear: a Hint of 3-D Printing’s Promise

Today’s 3-D printers can generally only build things out of one type of material—usually a plastic or, in certain expensive industrial versions of the machines, a metal. They can’t build objects with electronic, optical, or any kind of functions that require the integration of multiple materials. But recent advances in the research lab—including a 3-D printed battery and a bionic ear—suggest that this might soon change.

Last month, researchers unveiled what they say is the world’s first 3-D printed battery, made from two different electrode “inks.” Led by Jennifer Lewis, a professor of biologically inspired engineering at Harvard, the group used tiny nozzles to precisely deposit the anode and cathode inks, which contain nanoparticles of lithium titanium oxide and lithium iron phosphate, respectively. In a paper in Advanced Materials, the researchers described printing millimeter-scale rechargeable batteries, which could be used to power things like small wireless sensors and medical devices. The batteries, each of which can be printed in minutes, demonstrated impressive electrochemical performance.

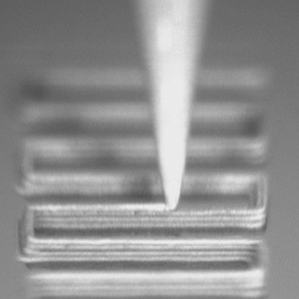

Lewis’s group has developed the materials and custom printer technology—including a nozzle that can print features as small as one micrometer—needed to print several different kinds of functional components besides batteries, including electrodes and antennas made from inks containing metallic nanoparticles, and optical structures made of photocurable resins. Now that she and her colleagues have built a palette of functional inks (her group holds eight patents) for digitally printing both 2-D and 3-D components, the next step is to try to make “integrated electronics,” says Lewis.

Whereas it may take many years before something as complicated as a smartphone will be printable, certain 3-D printed electronic products might not be too far off. Take hearing aids, for example, says Lewis. Companies already print the plastic shell that sits in the wearer’s ear cavity. The electronic components are assembled separately, and the devices use small batteries that must be replaced roughly every seven days. “Imagine if you could 3-D-print the entire hearing aid,” says Lewis. “We can print on curved surfaces.” The electrical components, and a rechargeable battery like the one her group just demonstrated, could thus be additively deposited within the plastic shell.

Opportunities that result from the ability to precisely deposit electronic or optical materials within 3-D printed objects are not limited to consumer electronics. In May, researchers at Princeton reported using an off-the-shelf 3-D printer to produce a computer-designed ear made of real tissue with interwoven electronics, including a coiled antenna and electrodes composed of a conductive polymer infused with silver nanoparticles. To print tissue, the researchers seeded a jellylike matrix with bovine cells. The matrix gave the printed ear its form as the cells developed into cartilage.

The researchers admit that the ear, which can detect radio frequencies, serves mainly as a demonstration. But it is nonetheless the first example of this kind of integration of biological tissue and electronics, and suggests a new additive manufacturing-based approach to tissue engineering.

The 3-D printed ear and Lewis’s battery—both produced using printers that extrude material through a nozzle—“open a window to the potential” of additive manufacturing for making things with more than one function, says Richard Hague, director of the EPSRC Center for Innovative Manufacturing in Additive Manufacturing at the University of Nottingham.

However, says Hague, if 3-D printing is to make an impact in a “robust manufacturing sense” over the long term, it will more likely be through other printing technologies—for example, advanced machines that use print heads like those in conventional inkjet printers. Research at his center is focused on overcoming the substantial materials-related obstacles to printing conductive materials in this way.

For now, Lewis’s group is exploring ways to commercialize its extrusion-based printers, which can print functional inks through nozzles as small as 100 nanometers and can be equipped with print heads capable of depositing inks from multiple larger nozzles at the same time. “I think there’s a pathway to manufacturing custom components,” she says. “At least that’s our vision.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.