Gigapixel Holographic Microscope Made From A4 Paper Scanner

Holograms fascinate people because of their ability to display three-dimensional information in a single two-dimensional image. But making holograms is hard, largely because of the huge amount of information that must be captured to get decent resolution.

That wasn’t a problem in the days of old-fashioned photography because photographic film had a resolution that put digital cameras is to shame. But the electronic CCDs required to do the same job must have gigapixel capability, something that is only possible with the most expensive equipment.

Astronomers, for example, have CCD chips with over 0.1 gigapixels. But the best digital cameras have only megapixel capability, which means that holographers have to rely on complex scanning protocols to get decent results.

Today, Tomoyoshi Shimobaba at Chiba University in Japan, and a few buddies, say they’ve worked out how to take high-resolution holograms without using expensive digital cameras. Instead, these guys have built a digital holographic microscope with gigapixel resolution using only a laser and a cheap digital scanner.

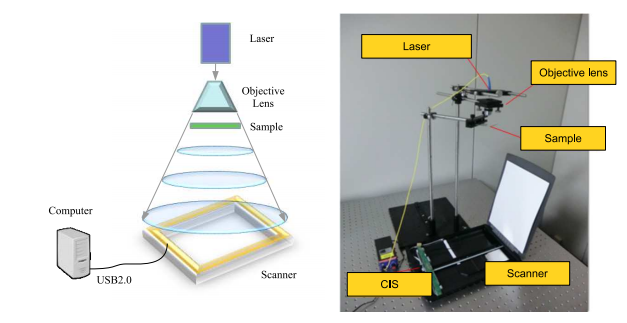

The setup could hardly be more basic. The simplest way to make a hologram is the so-called “in-line” method. This involves placing the laser, sample and recording medium in line with each other. The laser shines onto, and past, the sample. Any light that is diffracted by sample also interferes with undiffracted light, creating an interference pattern.

The difficult task is recording this interference pattern with the required resolution. But Shimobaba and buddies have done it with a standard A4 consumer scanner capable of recording at 4800 dpi.

That’s the kind of scanner that is probably gathering dust on your bookshelf or behind your desk. It works using a single line of light-sensitive CCDs that it scans down the length of the page. Theoretically, it is capable of achieving a resolution of 56,144 x 39,698 pixels. That’s over 2 gigapixels.

These guys have use their equipment to make holograms that are slightly smaller than this with 0.43 gigapixels. They’ve recorded a US Air Force 1951 test target as well as holograms of an ant and a water flea.

That’s entertaining work that makes it possible for almost anybody to make a high-resolution digital hologram at little cost.

One challenge they face is processing the huge amount of information that holograms generate. Shimobaba and buddies have some advice here. They say a data processing method known as “band-limited double-step Fresnel diffraction” significantly reduces the computational load compared with the traditional technique known as the angular spectrum method.

In this way they reduced the processing time to reconstruct the image on a standard PC from 350 seconds to just 177.

The only problem now is finding a good way to display these holograms. Standard computer monitors with a resolution of 1920 x 1080 pixels simply don’t cut the mustard when it comes to displaying gigapixel holograms.

Let’s hope somebody soon finds a cheap way out of this conundrum too.

Ref: http://arxiv.org/abs/1305.6084: Gigapixel Inline Digital Holographic Microscopy Using A Consumer Scanner

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.