Smartphone Tracker Gives Doctors Remote Viewing Powers

At the Forsyth Medical Center in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, nurses can see into the lives of some diabetes patients even when they’re not at the clinic. If a specific patient starts acting lethargic, or making lengthy calls to his mom, a green box representing him on an online dashboard turns yellow, then red. Soon, a nurse will call to see if he is still taking his medication.

This novel way of keeping tabs on patients is one of several studies of an app called Ginger.io taking place at hospitals in the United States. Once installed on patients’ smartphones, the app silently logs data about what they do and where they go. It’s looking for signs that something in their life has changed.

The company that makes the app, also called Ginger.io, was spun out of MIT’s Media Lab in 2011 from a group that applies computer algorithms to mobile-phone data to learn about the health of individuals and entire populations (see “Big Data from Cheap Phones”). That work, sometimes called “reality mining,” has shown that shifts in how people use their phones, and where they go, can reflect the onset of a cold, anxiety, or stress.

Anmol Madan, cofounder and CEO of Ginger.io, says that research suggested a new, inexpensive way to automate monitoring of people with conditions like diabetes or mental illness. They generally care for themselves, taking drugs at home, but they often stop taking medication if they get depressed. Then they run up medical bills when they have to see a doctor.

The Ginger.io app doesn’t diagnose patients directly. But it does warn that a person’s behavior has changed in ways that are linked to what doctors call “noncompliance” with a drug or treatment plan. With the app silently logging those changes, says Madan, “now the doctor or nurse can get a sense of the patient’s life and help as needed.”

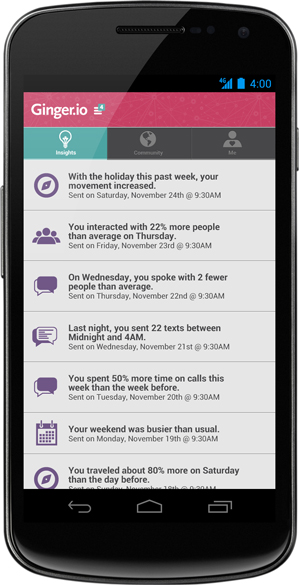

Ginger.io is available in both the Android and Apple app stores, but it can be activated only by a hospital or health-care company. Once installed, Ginger.io takes a few days to record the normal patterns of a person’s life. It collects motion data from a phone’s accelerometers; notes the places a person visits; logs the timing, duration, and recipients of phone calls; and records patterns in text messaging. After that, algorithms watch for any significant deviations and notify hospital staff if they occur.

One of the hospitals and health-care companies testing Ginger.io is Novant Health, which operates the Forsyth Medical Center and 13 other medical centers across the Carolinas and Virginia. Matthew Gymer, Novant’s director of innovation, says his group approached Ginger.io because it wanted an “early warning system” that could cut the number of times patients came to its clinics. Gymer declined to say how many patients are involved in Novant’s trial, but Madan says tests of Ginger.io typically start with hundreds of patients.

Eight months after Ginger.io was installed on the smartphones of some diabetes patients, it’s still too soon to say what the financial and health effects have been. But Gymer says patients “love the app because they have quicker access to caregivers” and that Novant is considering expanding the test to patients with heart problems or chronic back pain.

In the Novant trial, nurses respond to alerts generated by the app, but Madan says his company is working now on how to automate interaction with patients, too. For people with Crohn’s disease, which causes inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract, an automated message might ask about stomach pain, which may be an effective way to catch people on the verge of a flare-up. Other automatic responses the company is testing are a bit further from the methods of traditional medicine. “We’ve also explored the idea of sending a funny picture,” says Madan, “or messaging a patient’s friend suggesting they call.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.