Your Body Does Not Want to Be an Interface

The first real-world demo of Google Glass’s user interface made me laugh out loud. Forget the tiny touchpad on your temples you’ll be fussing with, or the constant “OK Glass” utterances-to-nobody: the supposedly subtle “gestural” interaction they came up with–snapping your chin upwards to activate the glasses, in a kind of twitchy, tech-augmented version of the “bro nod”–made the guy look like he was operating his own body like a crude marionette. The most “intuitive” thing we know how to do–move our own bodies–reduced to an awkward, device-mediated pantomime: this is “getting technology out of the way”?

Don’t worry, though–in a couple years, we’ll be apparently able to use future iterations of Glass much less weirdly. A Redditor discovered some code implying that we’ll be able to snap photos merely by winking. What could be more natural and effortless than that? Designers at Fjord speculate that these kinds of body-based micro-interactions are the future of interface design. “Why swipe your arm when you can just rub your fingers together,” they write. “What could be more natural than staring at something to select it, nodding to approve something?… For privacy, you’ll be able to use imperceptible movements, or even hidden ones such as flicking your tongue across your teeth.”

These designers think that the difference between effortless tongue-flicking and Glass’s crude chin-snapping is simply one of refinement. I’m not so sure. To me they both seem equally alienating–I don’t think we want our bodies to be UIs.

The assumption driving these kinds of design speculations is that if you embed the interface–the control surface for a technology–into our own bodily envelope, that interface will “disappear”: the technology will cease to be a separate “thing” and simply become part of that envelope. The trouble is that unlike technology, your body isn’t something you “interface” with in the first place. You’re not a little homunculus “in” your body, “driving” it around, looking out Terminator-style “through” your eyes. Your body isn’t a tool for delivering your experience: it is your experience. Merging the body with a technological control surface doesn’t magically transform the act of manipulating that surface into bodily experience. I’m not a cyborg (yet) so I can’t be sure, but I suspect the effect is more the opposite: alienating you from the direct bodily experiences you already have by turning them into technological interfaces to be manipulated.

Take the above example of “staring at something to select it”. When you stare at something in everyday life, you’re not using the fovea of your eye as a mental mouse pointer. You’re just looking at stuff. Mapping the bodily experience of “fixating my center of vision on a thing” onto a mental model in which “visually fixating on a thing equals ‘selecting’ that thing for the purpose of further manipulation via technology” is certainly possible. But it’s not at all “natural,” as the Fjord designers glibly assert. Looking is no longer just looking. It’s using your eyes as an abstracted form of “hands” in order to cater to some technological system.

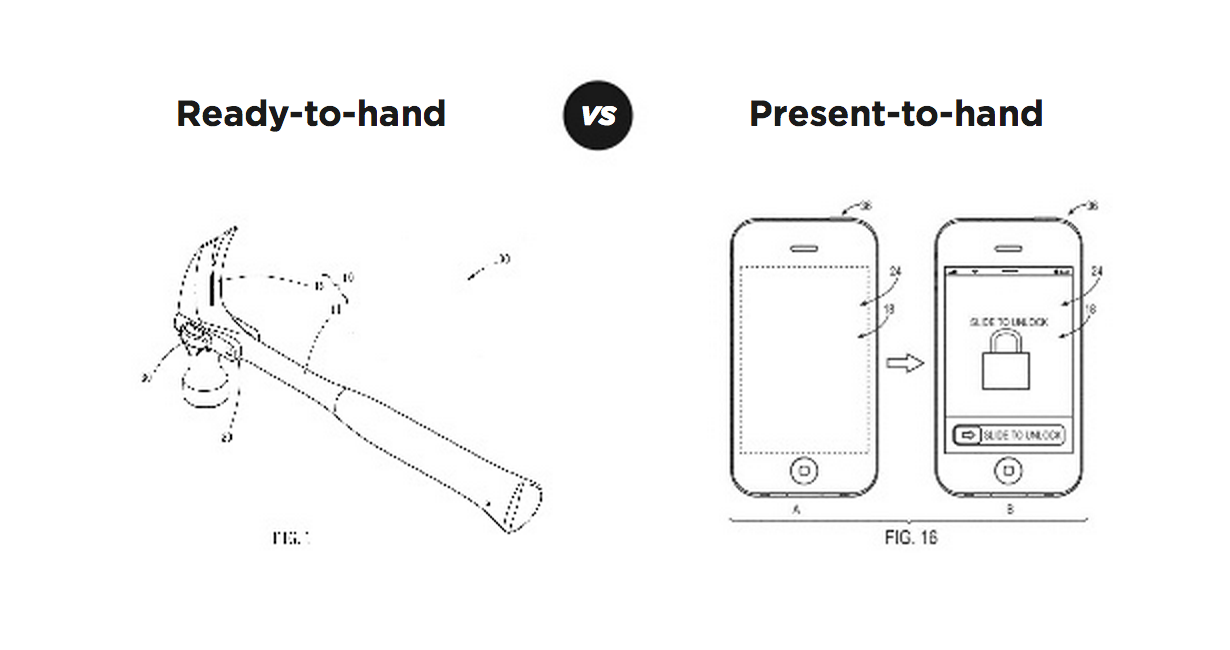

If this is starting to sound like philosophy, don’t blame me. In his book Where The Action Is, computer scientist Paul Dourish invokes Martin Heidegger (yikes!) to explain the difference between technology that “gets out of the way” and technology that becomes an object of attention unto itself. Heidegger’s concept of “ready to hand” describes a tool that, when used, feels like an extension of yourself that you “act through”. When you drive a nail with a hammer, you feel as though you are acting directly on the nail, not “asking” the hammer to do something for you. In contrast, “present at hand” describes a tool that, in use, causes you to “bump up against some aspect of its nature that makes you focus on it as an entity,” as Matt Webb of BERG writes. Most technological “interfaces”–models that represent abstract information and mediate our manipulation of it–are “present at hand” almost by definition, at least at first. As Webb notes, most of us are familiar enough with a computer mouse by now that it is more like a hammer–“ready to hand”–than an interface standing “between” us and our actions. Still, a mouse is also like a hammer in that it is something separate-from-you that you can pick up and set down with your hands. What if the “mouse” wasn’t a thing at all, but rather–as in the Fjord example of “staring to select”–an integrated aspect of your embodied, phenomenal experience?

In that case, your own body–your own unmediated, direct experience–would (could?) become “present at hand”: a control surface, an object, not-you, “in between” your intent and your action. You’d be “operating” aspects of your own embodied experience as if it were a technology: think of John Cusack’s character “driving” John Malkovich from the inside. If you ever saw that movie, you may remember that John Cusack’s character got pretty messed up by that experience. But this inner-homunculus-like dissociation of the self from the body, by turning it into a technological interface, is exactly what the designers at Fjord think would feel totally “natural”:

“Think about this scenario: You see someone at a party you like; his social profile is immediately projected onto your retina–great, a 92% match. By staring at him for two seconds, you trigger a pairing protocol. He knows you want to pair, because you are now glowing slightly red in his retina screen. Then you slide your tongue over your left incisor and press gently. This makes his left incisor tingle slightly. He responds by touching it. The pairing protocol is completed.”

Are they serious?

We want our technology to be ready-to-hand: we want to act through it, not on it. And our bodies don’t have to become marionettes to that technology. If anything, it should be the other way around.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.