Wanted: A Print Button for 3-D Objects

The largest companies in 3-D printing are racing to simplify design software so that it can become as easy to make an object as it is to send a document to a printer.

Interest in 3-D printing, also known as additive manufacturing, is exploding due to the falling cost of machines that can lay down finely targeted layers of plastic to make simple products, like jewelry or sculptures, much as a traditional printer sprays ink onto paper. The idea is that 3-D printers could democratize design and eventually manufacturing by letting anyone make physical things in small quantities, without the expense of an assembly line.

The technology still has a ways to go—making objects on consumer printers is slow and expensive. To print a solid plastic apple on MakerBot’s $2,000 consumer printer, for instance, takes seven hours and costs $50 in supplies, so it’s no competition for cheap plastic goods made in China.

But the bigger obstacle to a 3-D printing revolution is that few consumers or designers can actually operate the software used to render objects and turn them into files that can be printed. “A lot of people are 3-D printing other people’s designs, but they can’t yet model their own. They are in a holding pattern,” says Matthew Griffin, director of community support at Adafruit Industries, an online marketplace for high-tech hobbyists. “There is a gap between what they are seeing and what is inspiring them and what they can make.”

The problem is that the design software is too complex, says Igal Kaptsan, a vice president at PTC, a Massachusetts company that sells computer-aided design software. He spoke this week at Inside 3-D Printing, a conference in New York. Computer-aided design software creates shapes, or “geometries,” but it often takes expert knowledge to reliably translate these into files usable by a 3-D printer. Kaptsan’s company is working on software that would take a shape on a computer screen and print it directly. Other companies, including Autodesk and 3-D Systems, said they are developing similar software.

That means software innovation could be more important to 3-D printing than gradual improvements in the underlying technology for shaping objects. That technology is already 30 years old and is widely used in industry to create prototypes, molds, and, in some cases, parts for airplanes.

“The big change is going to be how people learn to use the technology to its fullest advantage,” says Scott McGowan, vice president of marketing for Solid Concepts, a company that builds objects on 3-D printers for Hollywood studios and other clients. “It’s a revolution inside designers’ and engineers’ minds.”

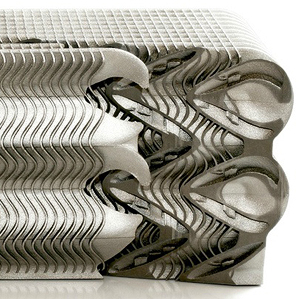

Although additive manufacturing allows for designs that can’t be made easily in any other way—such as complex shapes with internal cavities—so far, companies have mostly used 3-D printing to create prototypes or models of familiar products, McGowan says.

That’s beginning to change now as 3-D printing draws droves of hobbyists and some small-business owners. At the New York show, designers showed off ideas for how to use 3-D printing to create shoes, furniture, drones, and even edible food. Although most of these won’t ever be manufactured, “the 10 percent of the ideas that are any good are more than everything that we ever did before,” says Phil Reeves, director of Econolyst, a British consultancy that helps companies make use of 3-D printing.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.