“12 Hours of Separation” Connect Individuals on Social Networks

In 1967, the American social psychologist Stanley Milgram sent out 160 packages to randomly chosen individuals in the U.S. and asked that they be forwarded to a single individual living in Boston. The task included a simple rule: the recipients must send each parcel on to somebody they knew on a first-name basis.

To his surprise, Milgram found that the first package arrived at its destination via only two people. On average, he found, the parcels reached their destination via five pairs of hands, which amounts to six degrees of separation.

Milgram’s work has since been repeated on various social networks. For example, Microsoft says that people on its Messenger network are separated by 6.6 degrees, and Facebook claims its members are separated by only four degrees.

But there is another element to this work that has been less closely studied, which is the time it takes to travel across a network. In Milgram’s experiment, the first package arrived in just four days. But the others took significantly longer.

So an interesting question is how quickly is it possible to traverse a social network—to track down a random individual across the network.

Today, we have an answer thanks to the work of Alex Rutherford at the Masdar Institute of Science and Technology in Abu Dhabi and a few pals who have measured how quickly it is possible to track down random individuals around the world using social networks.

Their conclusion is that, on average, any individual is just 12 hours of separation from another.

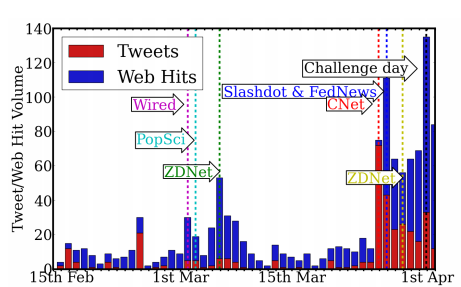

Their data comes from a competition called the Tag Challenge, run last year, in which the goal was to find five individuals in five different cities in North America and Europe. The only clue was a mug shot of the individual, the name of the city he or she was in, and the fact that he or she would be wearing a T-shirt with the logo of the event.

Rutherford and co won the competition by identifying three of the five individuals in just 12 hours.

Now they have analysed exactly how they achieved this feat and say a key factor is the ability of participants to target other individuals who may be to help. That’s in contrast to another strategy: blindly gathering as many different people to help as possible. “We have shown that this 12 hours of separation phenomenon relies crucially on the ability of social networks to mobilize in a targeted manner, using geographical information in recruiting participants,” they say.

Their data show that one in three messages were targeted in an appropriate way during the most time-sensitive part of the task. This indicates that social networks are able to tune their geographical communication to suit the task at hand.

And Rutherford and co say but it may be possible to get participants to react even more quickly using appropriate incentives.

That’s an interesting observation that may have important applications for the way politicians and grass roots organisations mobilise support. It may also help in emergency situations such as in tracking down individuals.

However, Rutherford and co fail to address the important question of false positives, when individuals who are not legitimate targets are falsely identified.

That’s unlikely when the target is wearing a T-shirt with the competition logo on it. But the recent social media frenzy over the Boston marathon bombings, and the erroneous finger-pointing that occurred on social networking sites such as Reddit, shows that this is an important factor.

Perhaps future work can throw more light on how false positives can be handled and avoided.

But given the significant impact that these kinds of mistakes can have on individuals, important questions remain over whether social media will ever be a suitable medium for tracking individuals in this kind of situation.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1304.5097: Targeted Social Mobilization In A Global Manhunt

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.