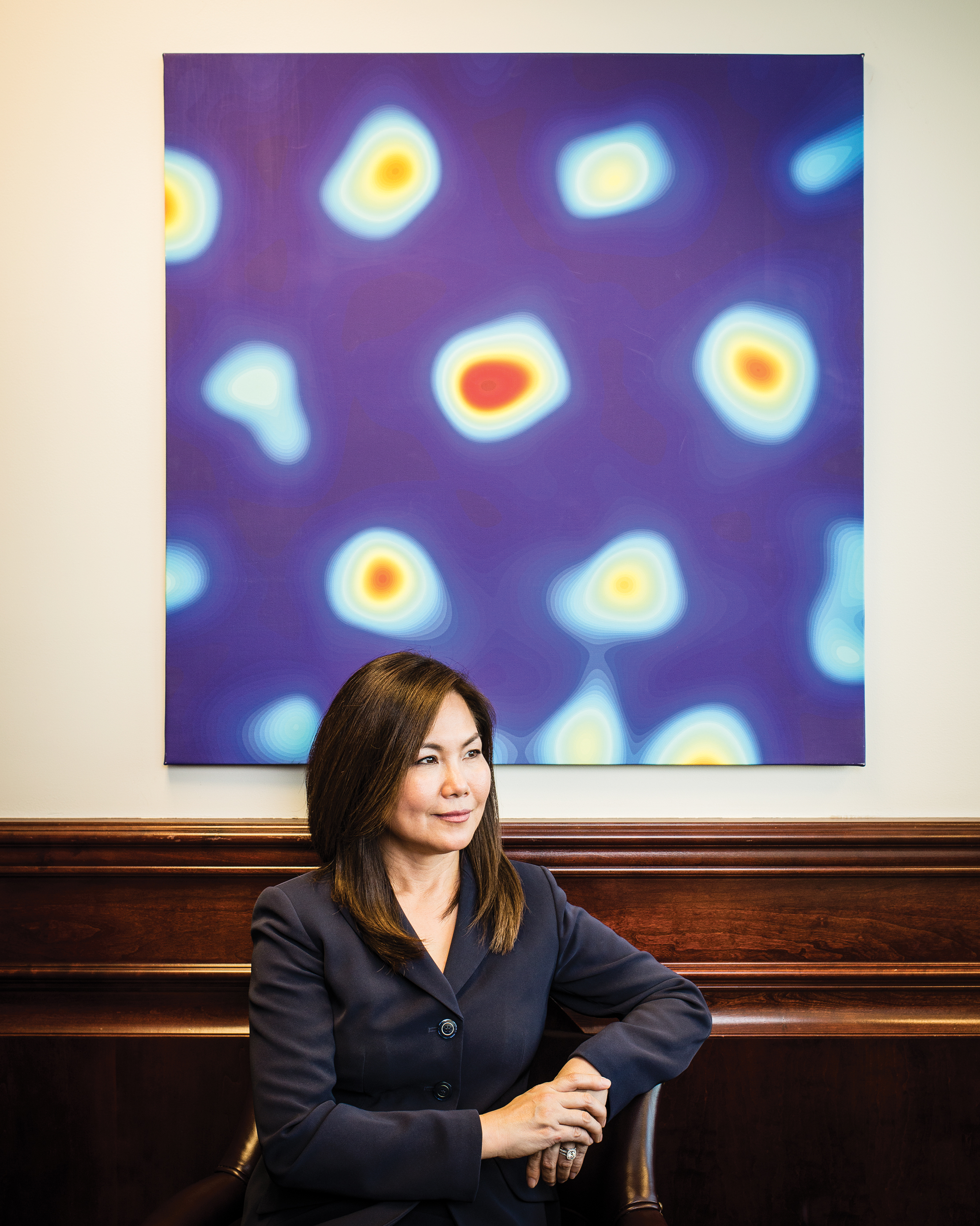

Interview with BRAIN Project Pioneer: Miyoung Chun

The Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies (BRAIN) project, which President Obama announced in his State of the Union address in February, will be a decade-long effort to understand the nature of thought (See “Why Obama’s Brain-Mapping Project Matters.”) The project, which inevitably evokes the Human Genome Project, will demand billions in research funding and require the coöperation of many government agencies, universities, and foundations. Miyoung Chun, a molecular geneticist and vice president for science programs at the Kavli Foundation, has been coördinating communication among those involved since planning began 18 months ago.

What do you hope to map, exactly?

We’ve made great strides since neurons were recognized [by Santiago Ramón y Cajal more than 100 years ago] as the basic functional unit of the nervous system. We know how to measure the activity of small numbers of neurons—up to a few hundred. Using functional MRI [magnetic resonance imaging], we also know how to measure the activities of patches of large numbers of neurons—from 30,000 to one million. But many critical brain functions involve anywhere from a few thousand to many millions of neurons.

BRAIN will generate revolutionary new tools to measure the brain activities in thousands to millions of neurons in order to produce a general theory of the brain.

Why do it?

We want to understand how we reason, how we memorize, how we learn, how we move, how our emotions work. These abilities define us. And yet we hardly understand any of it.

How will nanoscience and nanotechnology contribute to the brain activity map?

The brain functions at the nanoscale. So the tools to study brains must ultimately operate at this level as well. What’s really going to be needed is the ability to measure a lot more. Ten to 15 years ago, the time wasn’t right; now, it’s feasible.

What would be the benefits?

What’s the point of measuring more if you don’t understand what it means? The purpose of BRAIN is not just to develop tools so that we can read more neurons; we want to decipher brain activity. An interdisciplinary network of scientists and engineers will work to make new, powerful prosthetics, treatments for devastating brain disorders, improved educational strategies, and smart technologies that mimic the brain’s extraordinary abilities.

Is the Human Genome Project a good or dumb metaphor for the brain activity map?

There are similarities: the scope of the study, its long-term vision, and the amount of funding it will require. What’s dissimilar is the end point. In the case of the Human Genome Project, the end was very clear. As soon as you sequence three billion nucleotides, you’re done, right? But for the brain activity map, it’s probably imprudent to set a goal to measure the 100 billion neurons in the human brain. For one, we may never achieve such a goal; but more importantly, we don’t know if a smaller number will provide us the insights we need.

You also mean we can’t even anticipate some of the questions that will emerge from the mapping.

Precisely. We don’t know what we will learn by measuring and deciphering a million neurons. What we do know is what we have already been able to achieve. For example, John Donoghue [of Brown University] has a patient who had a stroke 15 years ago. By stimulating less than 100 neurons, she could move the arms of a robot and drink her morning coffee. A hundred neurons. Imagine: maybe this patient can walk on her own if John can stimulate 100,000 neurons!

I’d like to ask a private question, if I might. What’s the one question that the BRAIN project might answer that you long to understand?

I try not to personalize the project, to be honest.

Well, that’s why it’s an interesting question.

What’s most interesting to me is how our thoughts are molded. Thought seems such a human thing. We assume that other species have thoughts, but our thoughts appear to be more… comprehensive. It’s thoughts that led us—you and me—to talk about these issues today. Our thoughts are directly related to how we memorize, and how we learn, and how we are able to do so much. But what’s the basis for this? It’s the reasoning side of the brain that seems to me the most mysterious. But I would think that everyone has their own opinions on why mapping the brain is important.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.