Durable surfaces that can shed water could be useful in a variety of areas, including energy, water, transportation, construction, and medicine. The condensation of water is a crucial part of many industrial processes; most electric power plants and desalination plants, for example, have condensers.

Hydrophobic materials—which prevent water from spreading over a surface, instead causing it to form droplets that easily fall away—can make the condensation process more efficient. But most hydrophobic materials are made from thin polymer coatings that degrade when heated and are easily destroyed by wear. Now MIT researchers, including associate professor Kripa Varanasi and mechanical-engineering postdoc Gisele Azimi, have come up with a new class of hydrophobic ceramics that can endure both extreme temperatures and rough treatment.

Ceramics are great at withstanding extreme temperatures, but they tend to attract water rather than repel it. To address this problem, the MIT team made ceramics out of the so-called rare-earth metals—elements whose unique electronic structure they thought might render the materials hydrophobic.

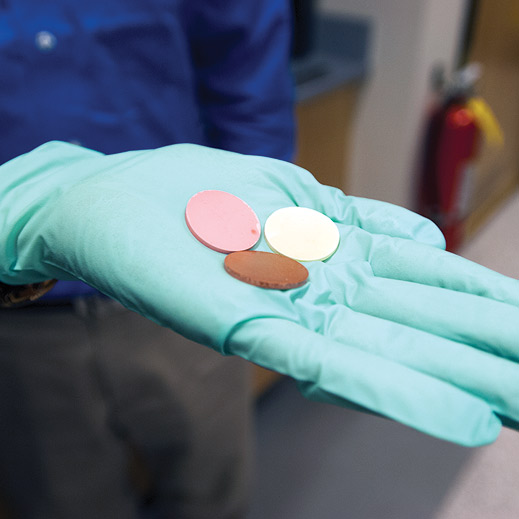

To test this hypothesis, the team used powder oxides of 13 of the 14 members of the rare-earth metal series (excluding one that is radioactive) and made pellets by compacting them and heating them nearly to their melting point in order to fuse them into solid, ceramic form—a process called sintering. “We thought they should all have similar properties for wetting, so we said, ‘Let’s do a systematic study of the whole series,’” says Varanasi, an associate professor of ocean utilization.

As predicted, all 13 displayed strong hydrophobic properties. “We showed, for the first time, that there are ceramics that are intrinsically hydrophobic,” Varanasi says.

The ceramic forms of rare-earth oxides could be used either as coatings on various substrates or in bulk form. Because their hydrophobicity is an intrinsic chemical property, Azimi says, it persists “even if they are damaged.”

Most previous research on hydrophobic materials and coatings has focused on surface textures and structure rather than on the materials’ chemical properties, Varanasi says. “No one has really addressed the key challenge of robust hydrophobic materials,” he says. “We expect these hydrophobic ceramics to have far-reaching technological impact.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.