Restoring the Studio of Artist Winslow Homer

When the great American artist Winslow Homer settled into his family’s compound in coastal Prouts Neck, Maine, in 1883, he began a spectacular era of productivity. Although he’d painted marine subjects before, his work took on new intensity with scenes of crashing ocean waves and brooding light. Today, thanks to a Portland Museum of Art restoration project guided by two MIT-trained architects, you can share the view he saw from his second-story balcony, which he called his piazza.

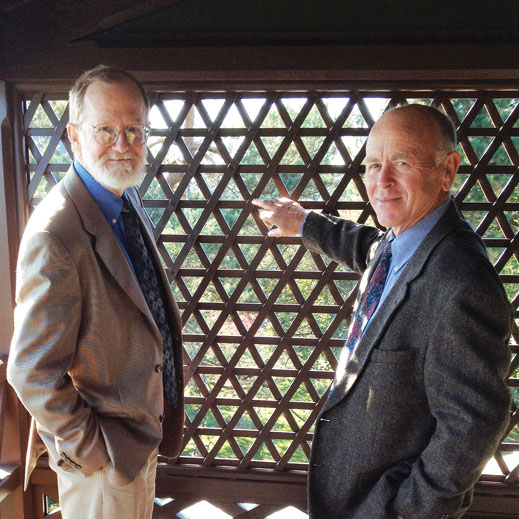

The architects, Don Mills, MArch ’84, and Craig Whitaker, MArch ’83, didn’t anticipate working in restoration architecture. They met in a hallway when Mills was visiting MIT and quickly became friends and colleagues; Whitaker enlisted Mills’s help the following summer on a residential renovation project. Over the years, they regularly consulted on projects, and in 1997 they formed Mills Whitaker Architects. Initially, their combined strengths included residential work, commercial structures, and institutional projects such as college and town hall buildings.

“When we got hired to work on historic properties,” says Mills, “we applied our collective knowledge of renovation work on older buildings.” As their expertise in the field grew, so did their opportunities. Now historic renovation constitutes the majority of their work. They have offices in Arlington, Massachusetts, headed by Mills, and Bridgton, Maine, headed by Whitaker.

“When I was in school and saw historic preservation projects, I said, ‘So what? You made it look like it used to look. Who would want to do that?’” says Mills. “I couldn’t have been more wrong in my ill-informed assessment of what was involved in preservation, restoration, and rehabilitation, the three things we do: preserving the building that is there, rehabilitating it to change to a compatible use without distorting its historic character, and restoration to take it back to its time period of significance. The Homer [studio] has been used for a summer cottage by the Homer family for 100 years, so it was restoration.”

Restoration architecture involves considerable detective work as well as compliance with local and national standards. The U.S. Department of the Interior, for example, publishes strict guidelines for the treatment of historic buildings. For the Homer studio, the architects had to pore over architectural plans, historic photos, and other archival records to discover how the building had been changed. Further, they had to incorporate technologies like modern HVAC systems, sprinkler systems, and security surveillance—and make them virtually invisible to the visitor’s eye. During the final construction phase, one more alumnus joined the team. Builder Marc Truant ‘78 was called in to incorporate modern heating and safety features—and to keep them out of sight.

The goal of the Portland Museum of Art, a world leader in scholarship on Homer and home to a substantial collection of his art, was to restore his home so visitors could step back in time for a fresh appreciation of his work and the influence of Maine’s coastal environment on it.

For the $2.8 million construction project, the museum directed the architects to recapture the building’s appearance circa 1910, the last year of Homer’s life. Original resources were essential. They examined the 1883 floor plans drawn by John Calvin Stevens, the architect who converted what had been a carriage house into a two-story home and studio. Mills dug out photos and drawings from the Bowdoin College archive that documented building features such as details of an original ocean-facing window that was replaced in 1939. Re-creating the style and shape of the window exemplified the meticulous attention to detail that took the building back in time.

Homer’s studio was a vernacular construction, mixing styles such as a mansard roof with Queen Anne brickwork on the chimney. Whitaker says the project sometimes reminded him of his MIT education, where the focus was not on “big glossy buildings” but on the authentic experiences of living and working in built environments. One professor, he says, talked simply about the value of PTS—places to sit. Some vintage Homer details in the restored studio include a flagpole the artist used to signal his desire for lunch to be delivered from a nearby restaurant and a wooden sign, marked “Snakes, snakes—and mice,” that he would sometimes put out in the yard to discourage casual visitors.

The Winslow Homer Studio, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, opened in September 2012 to tremendous media response, and the museum set attendance records in November for the accompanying Homer exhibit, “Weatherbeaten.” Tickets are now on sale for the spring tours, April 2–June 14. Learn more online: www.portlandmuseum.org.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.