Novel Designs Are Taking Wind Power to the Next Level

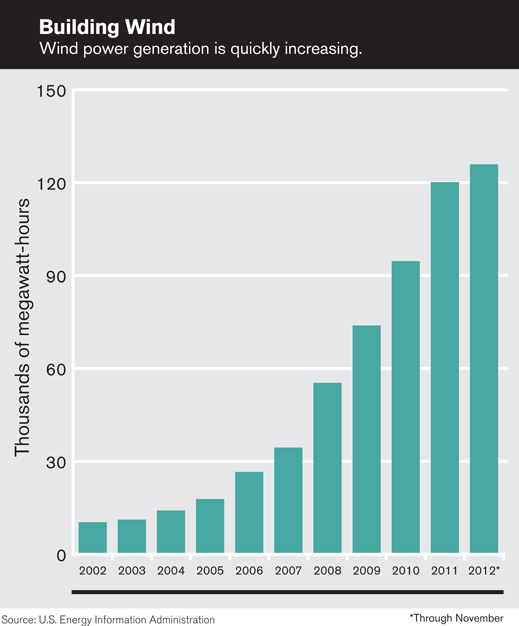

Superficially, wind turbines haven’t changed much for decades. But they’ve gotten much smarter, and considerably bigger, and that’s helped increase the amount of electricity they can generate and lower the cost of wind power.

GE’s new 2.5-120 wind turbine, announced last week, is a case in point. Its maximum power output, 2.5 megawatts, is lower than that of the 2.85 megawatt turbine it’s superseding. But over the course of a year it can generate 15 percent more kilowatt hours. Arrays of sensors paired with better algorithms for operating and monitoring the turbine let it keep spinning when earlier generations of wind turbines would have had to shut down.

The technology is part of a trend that’s made wind power almost as cheap as fossil fuels. In 1991, wind power cost 15 cents per kilowatt hour. The cost has now dropped to 6.5 cents per kilowatt hour, says Ryan Wiser, deputy group leader for Electricity Markets and Policy at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, in Berkeley, California. New natural gas power plants are expected to generate electricity at about 6.5 cents per kilowatt hour.

A new generation of more productive wind turbines that’s coming on line this year could be what it takes to make wind widely competitive with fossil fuels.

Indeed, last month the Electric Reliability Council of Texas said that the latest data on wind turbine performance and costs suggests that wind power is likely to be more cost-effective than natural gas over the next 20 years, and it could account for the majority of new generating capacity added over that that time in Texas. Before the council factored in the latest data, it had expected all new generation to come from natural-gas plants.

The biggest impact on electricity production comes from making wind turbines bigger. Increasing the size of a wind turbine’s blades, and making the tower taller, allows a turbine to capture more wind, especially at low speeds. Making wind turbines larger is getting difficult, in part because they’ve have grown so large that the wind conditions at the highest point of the blades’ sweep can be very different than those at the bottom. To compensate for the difference, GE had to develop control algorithms to respond to input from a variety of sensors as the blades spin. This helped the company step up from a 100-meter-diameter wind rotor to a 120-meter one.

Avoiding downtime from mechanical failures also helps boost electricity production. If something goes wrong with a wind turbine, it’s often shut down until technicians can arrive, climb the tower to assess the problem, and then make repairs—a process that can be especially difficult and time-consuming because wind farms are often located in remote areas. With its latest design, GE is networking its wind turbines to make them more resilient. For example, if the wind speed gauge on one wind turbine fails—say, because it becomes encased in ice—the turbine can use data from a nearby turbine’s anemometer (with algorithms for correcting for the different locations of the turbines), eliminating the need to shut down.

The National Renewable Energy Laboratory in Golden, Colorado, is studying how the turbines within a wind farm can adjust their power production to maximize the power output of the entire farm. For example, if some wind turbines at the front of a wind farm produce less power than they’re able to, this could leave more wind for the other turbines. “It’s a shift from thinking about individual wind turbines to thinking about power plants,” says Fort Felker, director of the National Wind Technology Center at NREL.

Just over a decade ago, a typical wind farm with 2.5 megawatts of wind turbines generated less than 4 million kilowatt hours of electricity per year. GE says its new wind turbines will generate 10 million kilowatt hours a year, more than doubling electricity production. (Increasing power output helps lower the price per kilowatt hour, as long as the cost of the installed turbine doesn’t increase proportionally.)

Technology improvements may have brought the price of wind within reach of that of fossil-fuel power, but the scale of wind will be limited by the grid’s ability to handle the inherent intermittency. Smarter wind turbine designs are helping with that as well. GE’s new wind turbine comes with battery backup. New algorithms, paired with weather-prediction software, determine when to store power in the battery and when to send it to the grid. As a result, wind farm operators can guarantee power output—but for just 15 minutes at a time. If wind power is ever to provide a large share of the total electricity supply, it may be necessary to have hours of storage—or else grid operators will have to maintain backup sources of power, such as natural-gas power plants.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.