For Energy Startups, a Glass Half Full or Empty?

It’s no secret that times are tough for funding clean technology startups. But innovators are adapting to the many things that have changed since the go-go years of the mid to late 2000s.

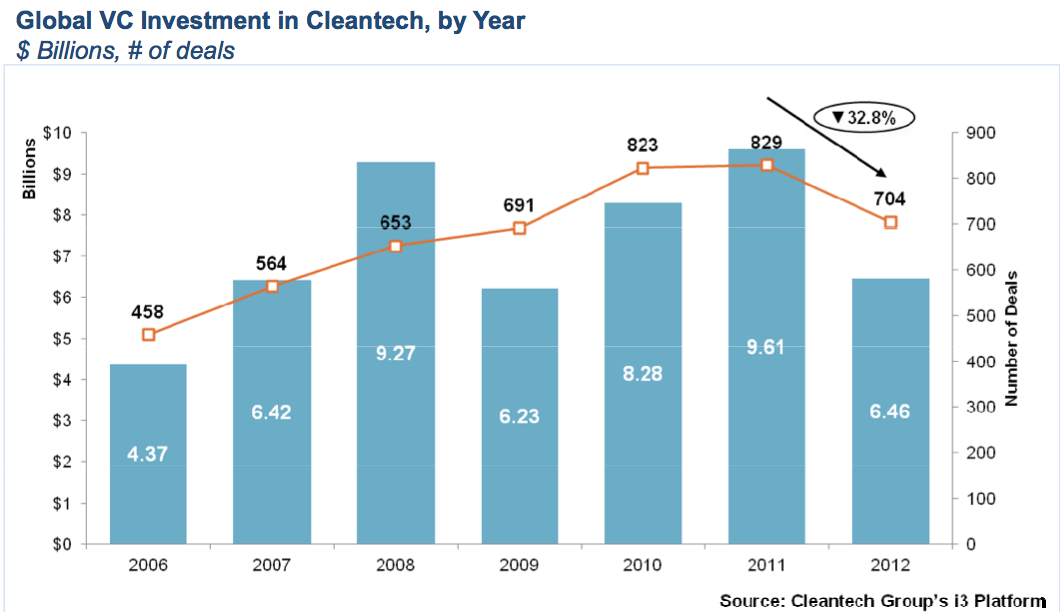

Research company the Cleantech Group yesterday released data showing just how much venture investors have soured on clean technologies, with the amount of money invested into clean-tech startups plummeting 33 percent last year to $6.46 billion.

Even though fewer startups are being funded, innovation in energy and environment continues, albeit under very different business conditions. Here are some thoughts on the business and technology trends shaping this year.

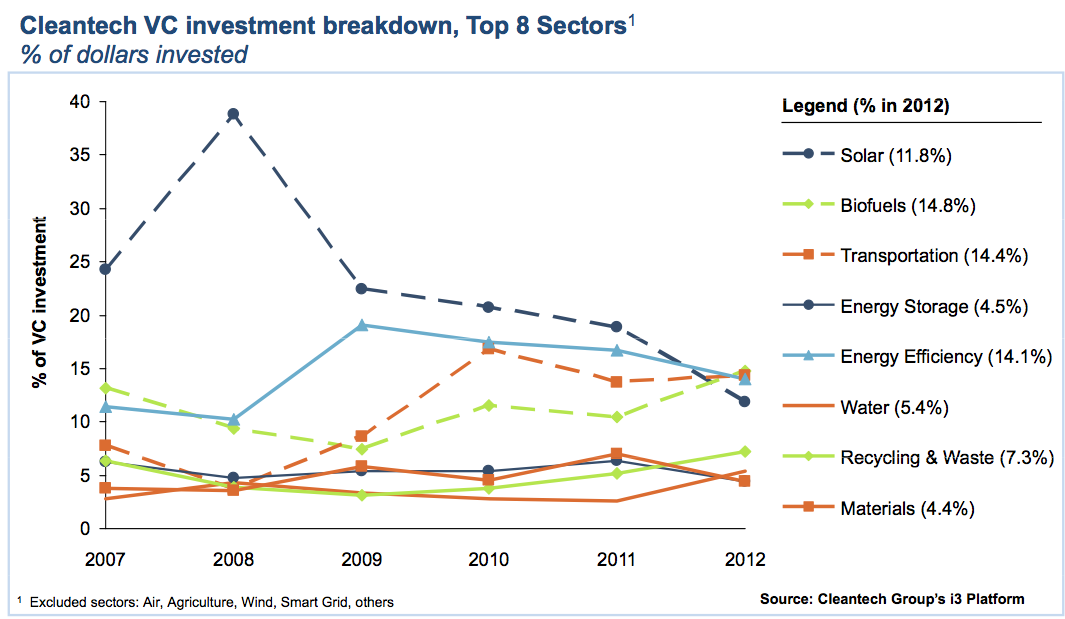

A smaller investor pool. Back in the mid 2000s, nearly all generalist venture capital firms had an investment in the clean tech category with solar and biofuels getting most of the money. Now, the venture investing is left primarily to specialist companies, as others have fled.

The Cleantech Group’s numbers reflect this. In addition to a lower total amount invested, the number of deals fell over 30 percent, too, and the average deal sizes are lower. Many venture capital companies “got burned” in previous years when they underestimated how much capital is required to bring an energy-related startup to an IPO or sale, says Sheeraz Haji, the president of the Cleantech Group.

Corporate investors, such as ABB or General Electric, have helped fill the funding needs for startups, but these “strategic investors” are cautious and there’s been a decline in their involvement over the past year, says Haji. Meanwhile, raising money on the public markets via an IPO is effectively shut and a number of companies cancelled stock offerings. SolarCity did have a successful IPO but had to scale back how much it sought to raise, which its chairman Elon Musk blamed on investors skittish of clean tech.

The continued marriage of energy and IT. Energy has traditionally meant drilling, but it’s becoming increasingly high tech. This is driven in part by investment patterns. Wary of funding companies that will require big sums of money and long technology development periods, VCs are putting their money into “capital-efficient” startups geared at energy efficiency. One hundred and forty of the 700 deals Cleantech Group recorded last year were in energy efficiency.

A number of companies have rightly estimated that buildings could be more efficient by analyzing data or using sensors to cut back on wasted energy. One startup called Stem analyzes building energy consumption patterns and electricity rates and then uses an on-site battery to lower electricity bills. (See A Startup’s Smart Batteries Reduce Building’s Electric Bills.)

But this area has become overcrowded. There are now dozens of building and utility data analytics companies and Haji notes that some, such as Serious Materials, have had to abandon plans to offer energy management services to building owners. Investment dropped 21 percent in energy efficiency, which is also hurt by muted electricity prices.

A more promising area is using embedded computation and communication, such as networked sensors, to make energy more efficient, a form of what people call the Internet of things. An example in the area of sensors is Enlighted, a lighting company that uses light and motion sensors to improve lighting controls and save energy. General Electric, meanwhile, is pushing heavily into the “industrial Internet” by equipping everything from jet engines to medical devices with controllers and sensors to analyze data and improve equipment performance.

Cheap Fossil Fuels Give and Take away. Natural gas has rapidly displaced coal in power generation and super cheap natural gas in the U.S. makes it harder for solar and wind to compete on price. (See What Mattered In Energy Innovation This Year.)

But the domestic fossil fuel boom is creating the need for better analytical tools in exploration and monitoring the entire distribution system, Haji says. And the drilling technique behind the U.S. oil and gas boom—fracking—creates the need for water treatment technologies. Cheap natural gas also makes stationary fuel cells and natural gas vehicles more attractive.

Meanwhile, more companies are trying to make use of natural gas to make chemicals and even fuels. For example, Siluria has a process for making the chemical ethylene from natural gas rather than oil while Calysta Energy and Primus Green Energy, once a biofuel company, are using natural gas to make liquid fuels. (See Biofuel Companies Drop Biomass and Turn to Natural Gas.)

Efficiency, not electrification, is the name of the game in cars. Electric vehicles are coming, but expect a long transition. The shorter range and high cost of battery-electric vehicles limits their appeal to a small audience of people, while hybrids offer better fuel economy without range limitations. Sales data from big automakers indicate that consumers a showing preference for plug-in hybrids over all-electric cars. (See Consumers Voting for Plug-in Hybrids Over EVs.)

But as automakers looks to meet more stringent fuel economy standards in the U.S. and other countries, electrification is just one tool among many. Expect to see more advances in the internal combustion engine and efficiencies gained through lighter materials and more aerodynamic body designs.

By the end of this year, BMW is expected to release the i3 plug-in hybrid that uses a carbon fiber body, a sign that alternative materials have attracted serious attention from auto manufacturers.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.