What Yoda Taught Me About 3-D Printing

Will we one day find a desktop factory in every American home? That’s what enthusiasts of 3-D printing technology believe.

To find out how plausible such predictions are, I sat in on a 3-D printing class at the San Francisco branch of TechShop, a studio for tinkerers and designers, where I found myself waiting to see a palm-sized toy model of the Star Wars character Yoda materialize from a spool of cheap fluorescent green plastic.

Unfortunately, the classroom’s 3-D printer, a desktop model made by the Beijing-based Delta Micro Factory, was acting finicky. Though my instructor had recently replaced some parts, he was now on his fifth attempt to demonstrate how we could print out Yoda from a file he’d downloaded from the Internet. As a stringy nest of half-melted thermoplastic accumulated on the printer’s platform, he acknowledged that this Yoda simply wasn’t meant to be.

Manufacturing and design companies have already found powerful uses for high-end 3-D printers to quickly produce prototypes and make customized parts on demand (see “Layer by Layer”). What’s said to be coming next is a consumer mass market, and perhaps a radical economic shift as consumers stop shopping and start making what they need.

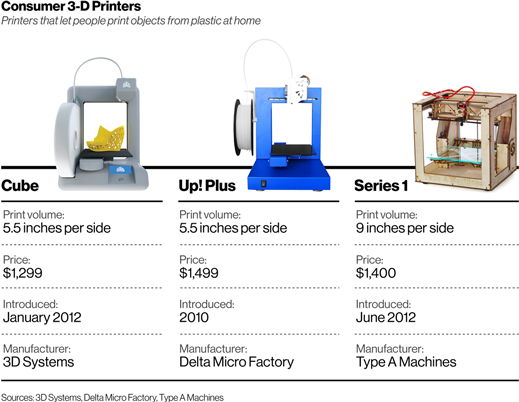

Fueling such thinking is a rapid increase in the number of affordable 3-D printers. The winter 2013 issue of Make magazine, a publication for hobbyists, lists 15 different models, with prices starting around $500. The head of MakerBot, a company that recently opened a fancy retail store in Manhattan to sell $2,199 3-D printers, has called the technology the start of “the next industrial revolution.”

Many do-it-yourself types believe the technology will become mainstream, despite what they agree are the significant limitations of today’s models. “Did anybody look at the computer mainframe or the Apple I and say, Oh look, there’s going to be one of these in every home? No,” says Andrew Rutter, a former lighting engineer who’s founded a startup, Type A Machines, to start making and selling a personal 3-D printer. But he and others expect them to take off as personal computers did.

The term “3-D printing,” coined at MIT in the mid-1990s, describes a set of methods that vary widely in price, complexity, and capability. High-end industrial 3-D printers cost $75,000 and more, and some can build from materials as diverse as steel and ceramics.

Most consumer models use a relatively simple process called fused deposition modeling, invented and patented in the late 1980s by S. Scott Crump, cofounder of the industrial 3-D printing company Stratasys. As in a hot-glue gun, a length of special plastic is melted and fed through a nozzle. As gears guide the nozzle up, down, and around over a platform, the plastic is deposited in layers that harden, and a three-dimensional object takes shape.

The big drawback for consumers is that 3-D printers are still tricky to use and very limited in what they can make. The objects they produce are not just fairly crude but quite small, since the thermoplastic will warp at larger sizes. What’s more, thermoplastics are just the kind of cheap, brittle material many people hate. The hardware requires precise calibrations that will be beyond the patience of many users and operating the software is significantly more complicated than clicking “Print” from a Word document.

Another problem: once you’ve made yourself an iPhone case and a Yoda bust, what else is worth making? The answer is not entirely obvious, says Eric Wilhelm, founder of Instructables, an online catalogue of how-to tutorials. Wilhelm, who has been tracking the 3-D designs being created, says the bulk of them are models of people’s heads, often their own.

The constraints of the at-home technology explain why the latest shift in consumer 3-D printing is toward centralized facilities not unlike photocopy shops. Last year, the office store Staples said it would test a service called “Staples Easy 3-D”: customers could send in a design and then pick up the finished product. Another company, Shapeways, has opened the largest such facility yet, in New York City. It aims to print three to five million objects a year on higher-end printers, using materials that include ceramics, stainless steel, and silver.

According to the online price calculator Shapeways offers, a version of my four-inch-tall plastic Yoda would cost about $20, with a delivery time of eight to 14 days.

As the ancient Jedi himself might have said: “Order one, I will not.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.