Cartography on the Fly

MIT researchers have developed a tool that they hope will be useful for emergency responders: a wearable sensor system that automatically creates a digital map of the wearer’s environment.

In experiments, a graduate student wearing the system wandered the MIT halls, and the sensors wirelessly relayed data to a laptop in a distant conference room. Observers in the conference room tracked the student’s progress on a map that sprang into being as he moved.

“The operational scenario that was envisioned for this was a hazmat situation where people are suited up with the full suit, and they go in and explore an environment,” says Maurice Fallon, a research scientist in MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory.

One of the system’s sensors is a laser rangefinder, which sweeps light in a 270° arc and measures the time it takes to return. Automatic mapping systems mounted on robots have used rangefinders to build very accurate maps, but a walking human jostles the rangefinder more than a rolling robot does. Similarly, sensors in a robot’s wheels can provide data about its physical orientation and the distances it covers, which is missing with humans. And because emergency workers might have to move between floors of a building, the new system also has to recognize changes in altitude.

In addition to the rangefinder, the researchers equipped their sensor platform with accelerometers, gyroscopes, and a camera. The gyroscopes can infer when the rangefinder is tilted—information the mapping algorithms can use in interpreting its readings—and the accelerometers provide information about the wearer’s velocity and about changes in altitude.

Should there be any discrepancies in the data from the sensors, the camera serves as the adjudicator. Every few meters, the camera takes a snapshot of its surroundings, and software extracts about 200 visual features from the image—patterns, contours, and inferred three-dimensional shapes. During different passes through the same region, the readings from the other sensors may diverge slightly, but image data can confirm that the region has already been mapped.

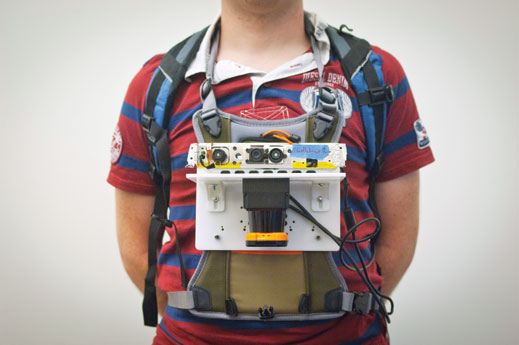

The system prototype consists of a handful of devices attached to a sheet of hard plastic about the size of an iPad, which is worn on the chest like a backward backpack. The only sensor that can’t be made much smaller is the rangefinder, so in principle, the whole system could be shrunk to about the size of a coffee mug.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.