What Sinofsky’s Departure Suggests about the Current State, and Likely Future, of Microsoft

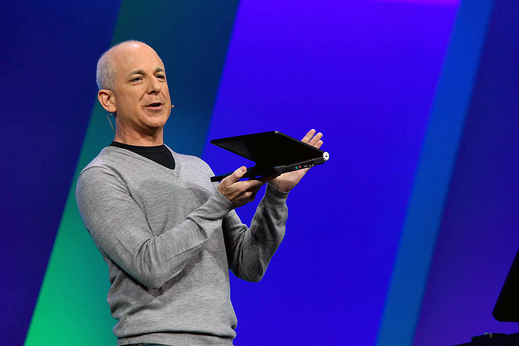

Steven Sinofsky, president of Microsoft’s Windows division, abruptly left the company on November 12, shortly after introducing the latest version of the company’s flagship operating system, Windows 8.

Reportedly, Sinofsky did not get along well with other senior executives at a time when Microsoft needs to promote more coördination across its product groups. Microsoft is a large company with many talented executives. But this is no trivial departure and raises serious questions about what the company has done recently and where it will go from here.

I interacted several times with Sinofsky beginning in the early 1990s, when he was on a two-year assignment as the technical assistant to Bill Gates and I was writing Microsoft Secrets, published in 1995. He had entered the company in 1989 as a software engineer. After the assignment with Gates ended in 1994, he joined the newly formed Office group as head of program management. Sinofsky and Office VP Chris Peters, along with development lead Jon DeVaan, had to figure out how to build a complex multiproduct suite consisting of previously separate products—Word, Excel, and PowerPoint—that competed aggressively for revenue. The new Office unit eventually adopted a common spec as well as techniques such as “daily builds,” “milestone” subprojects, and continuous debugging and integration testing. Office soon became a model of discipline and shipping software on time.

By contrast, the group that shipped Windows 95 had evolved from a less structured “hacker” culture and kept adding headcount to meet the challenge of building Internet Explorer and then other new capabilities. It got seriously bogged down in the Longhorn project of the early 2000s as engineers tried to add too many complex features too quickly. The Windows product at this point had ballooned to about 50 million lines of “spaghetti code,” with as many as 7,000 programmers and test engineers desperately trying to finish, debug, and stabilize the system. The daily builds crashed on a daily basis, making shipping the product on time in 2003 impossible. With the blessing of Chairman Bill Gates and CEO Steve Ballmer, DeVaan and then Sinofsky gradually exerted more influence on the Windows development process. By 2006, they had formally taken charge. Sinofsky and DeVaan led a re-architecting of the spaghetti code into smaller, less coupled modules, scaled back the feature scope, and incorporated a lot of code from the more stable Windows server product. Microsoft started shipping Vista before the end of 2006 and had a global release in January 2007.

Although many users disliked Vista, it is difficult for outsiders to appreciate the scale and scope of what Sinofsky and DeVaan achieved. The Windows group had become a fragmented empire ruled by competing fiefdoms, with their own leaders, agendas, and armies of programmers and testers. Getting so many strong personalities to work together required a very forceful hand and much more discipline than the Windows desktop group had ever accepted. Prior managers had all struggled, which is why most Windows versions were late and bug-ridden. Then, when Windows 7, a quick but well-crafted upgrade to Vista, shipped on time in July 2009 to significant acclaim, Ballmer named Sinofsky president of the division.

For his next challenge, Sinofsky and his team set out to redesign even more of the operating system, not just the core modules but also the process and organization used to build them. For what became Windows 8, they promised a new interface built from scratch for touch screens as well as an underlying architecture relying on smaller modules that Microsoft could update more easily and use to deliver Windows Live via the Web. Sinofsky took charge of these desktop and Web initiatives. No doubt he bruised some egos while reining in the different Windows fiefdoms. Again, though, his team delivered.

The president of the Windows division is probably the most powerful executive in the company after the CEO, so Sinofsky had a good shot to succeed Ballmer as the next head of Microsoft. He leaves the Windows group in far better shape than it’s ever been, and Windows and Office, both of which excelled under Sinofsky, remain the equivalent of modern-day gold mines. Now Microsoft has lost its most accomplished executive, someone willing to bruise egos and take big risks, such as moving the Office team to Windows and leading a major redesign. Sinofsky also championed Microsoft’s entry into the tablet market with Surface. So what does Sinofsky’s departure suggest about the current state and likely future for Microsoft?

First, it is important to note that Microsoft’s financials remain in very good shape. Yes, its market value has stagnated for more than a decade due to the company’s focus on the personal computer and the slow (and even declining) growth in this market. By contrast, much faster growth in media players, smartphones, tablets, digital media, software app stores, and Internet advertising has driven up the market values of Apple and Google. Someone should take the blame for Microsoft’s inability to diversify, but probably not Sinofsky. The bottom line is that Windows and Office together account for about half of sales and three-fourths of Microsoft’s impressive profits. Moreover, most of Microsoft’s revenues (about 70 percent) come not from the volatile consumer market but from largely recurring (so far!) business-to-business and enterprise sales (mainly PC manufacturers and large corporations).

The problem is that the PC market is shrinking relative to smart phones and tablets. Microsoft has only a couple of percent share in these newer markets. Its alliance with Nokia has yet to provide much in the way of new sales. So redesigning Windows for touch screens and creating a Microsoft tablet are potentially very important strategic moves. They target the billion or so Windows users who might want to use fully functional Windows applications on their smart phones and tablets, which they cannot do with Apple and Google Android-based products.

But here we also have plenty of room for disagreements among Microsoft executives and for conflicts with strategic partners such as Dell, Lenovo, Hewlett Packard, Intel, Samsung, and many more. Not only did Sinofsky champion the design of a Windows tablet by Microsoft itself, ignoring that hardware margins generally pale in comparison to software margins. He also kept the details secret. When it came out, we saw that, unlike the iPad or Android tablets, Surface has a solid keyboard and can easily substitute for a laptop computer. Bad news for hardware partners!

Sinofsky also had the Windows division introduce a tablet that runs something called “Windows RT.” This operating system works with a low-power microprocessor designed by ARM, which we can find in most smartphones and tablets running Google Android and earlier Apple versions of the iPhone and iPad. But what about the thousands of software applications already written and that will be written for traditional Windows machines, including the standard version of Windows 8? They all rely on microprocessors following the Intel x86 architecture and will not work with Windows RT. Bad (and confusing) news for customers and the vast Windows ecosystem of software developers!

Microsoft must move beyond the desktop as the smartphone and tablet markets expand. But the company should make this transition by leveraging rather than destroying the Windows ecosystem. Gates saved the company in 1995 when he issued his “Internet Tidal Wave” memo and redirected the company to “embrace and extend” Windows to accommodate rather than fight the Web. Microsoft needs to do this again with newer platforms. It has benefitted greatly from not competing with its partners and not losing compatibility with prior versions of Windows. True, Ballmer has allowed the Microsoft divisions to operate too independently and conservatively; better coordinating and even centralizing their efforts under one executive could help the company become more competitive.

But here is where Sinofsky seems to have fallen too short. He has not shown much willingness to work with other executives in Microsoft nor assuage the very real fears of external partners who worry about the entry into hardware or whether they should build apps for Windows 8 or Windows RT. A CEO needs to be able to do more than manage projects efficiently, even big projects.

When great companies lose their founders, they often lose the force that kept them together. Not surprisingly, Microsoft has become increasingly difficult to manage since Bill Gates got sidetracked with the antitrust trial in the late 1990s and then handed the CEO job to Ballmer in 2000. Apple is also experiencing more internal arguments and executive departures now that Steve Jobs is no longer around. Microsoft tried to bring in a new leader in Ray Ozzie, of Lotus Notes fame. He joined as CTO in 2005 and helped ease Microsoft into the age of cloud computing. But Ozzie did not run any of the main product groups and had relatively little influence compared to Sinofsky. He quietly left in 2010.

The danger for Microsoft going forward is that it will now be run by a committee of executives who work better together but lack the focus and “edge”—the discipline and willingness to exert power and take risks—that we have seen with Steven Sinofsky. At some point, like IBM and Apple have done, Microsoft will need to reinvent itself. It is no longer clear who will lead that charge.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.