Astronauts Could Remotely Control Moon Rovers from Lunar Orbit, Says NASA Plan

The demise of the space shuttle has forced NASA to scale back its human activities in space. Without its own vehicles for launching astronauts into space, there is little the organisation can do but dream of better times ahead.

Its current plan is to build a vehicle called Orion that will have the capability to support a small crew for up to 21 days, long enough to get to the moon and back. NASA is also greedily eyeing other potential destinations, such as near Earth asteroids.

Today, Jack Burns at NASA’s Lunar Science Institute in Moffet Field, California, and a few buddies have come up with another suggestion. These guys say that a moon landing is a risky goal so why not try an easier, intermediate mission first.

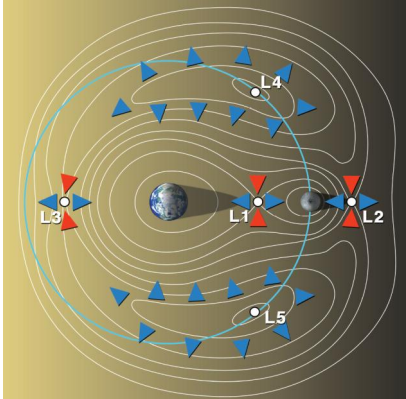

Their idea is to send an Orion spacecraft on a lunar fly-by past the moon to the L2 Lagrange point some 65,000 kilometres beyond. This is the place where gravitational forces exactly balance the spacecraft’s centripetal force, allowing it to seemingly hover above the moon (although in reality it will orbit the L2 point).

The advantage, say Burns and co, is that from L2, the astronauts will be able to see both Earth and the far side of the moon at the same time.

From here, the astronauts will operate a remote-controlled rover on the far side of the moon that will be sent ahead of the crewed mission.

Remote control from L2 will be much better than from Earth, say Burns and co. That’s because the round-trip communication time between the rover and L2 is only 0.4 seconds, compared to the almost 3-second round-trip time to Earth.

Experiments on Earth suggest that an 0.5 second delay is the maximum “cognitive horizon” that humans can cope with and still achieve a telerobotic presence.

Burns and co say the mission will have two science goals. The first is to explore the Schrodinger Impact Basin, a crater inside the immense South Pole-Aitken basin, which is probably the oldest impact crater in the inner solar system.

Planetary geologists hope that rocks from the region will span much of the lunar history, providing unprecedented data about our closest neighbour’s history and evolution and therefore possibly our own.

The second goal will be to deploy a low frequency radio telescope on the lunar farside capable of peering at the first objects that lit up in the universe’s distant past. The idea is to deploy the telescope—essentially thin plastic film covered in a conducting layer—using the same remote-controlled rover.

This kind of astronomy simply isn’t possible on Earth, or in orbit around it, because of radio pollution at these frequencies. The far side of the moon is, of course, shielded from these broadcasts.

All this will take some 30 to 35 days, which is longer than Orion is designed to support. However, Burns and co say relatively straightforward modifications could extend the craft’s range, such as adding an additional water tank and increasing the diameter of the oxygen tanks.

So what to make of such a plan? It certainly makes sense to increase the ambition of the human spaceflight program in incremental steps rather than giant leaps. It’s also a good idea to explore the far side of the moon and to take advantage of its unique radio-quiet environment.

But little else about the proposal makes much sense. The team argues that testing telerobotic presence is an important stepping stone for future missions to Mars, where the first crews will probably just remain in orbit and send a rover to the surface.

Perhaps. But Mars missions are so far in the future that autonomous robotic missions will almost certainly be more capable than human-controlled ones by then (and arguably are now).

And the team seems to have overlooked the possibility that a radio telescope could be deployed automatically on the lunar surface, just like numerous other space-based telescope. Why a telerobotic mission is needed to do the job isn’t clear.

Finally, there is the cost. Burns and co haven’t attempted to calculate what their human mission to L2 would cost. But that’s probably for the best since a true reckoning would almost certainly be impossible to justify.

NASA and its employees are entitled to dream about a future in which humans once again begin to explore deep space. But they’ll need better justifications than this.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1211.3462 : A Lunar L2-Farside Exploration and Science Mission Concept with the Orion Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle and a Teleoperated Lander/Rover

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.