Google Earth Finds More Strange Patterns in the Chinese Desert

Google Earth has a history of revealing strange objects in the deserts of China.

ast year, various websites reported the discovery of giant kilometre-sized concentric circles of military objects including jets in the Gobi desert. Analysts think these may be missile target zones.

Others websites reported the discovery of mysterious networks of lines in the Gobi desert. Some analysts believe these are designed to look like the networks of roads in a city and have been laid out in tehdesert so that nuclear missile guidance systems can use them for target practice.

Today, Amelia Carolina Sparavigna at the Politecnico di Torino in Italy reveals another mysterious pattern in a remote part of China, this time the Taklamakan desert in western China.

In the last few years, Sparavigna has pioneered a form of armchair archaeology using Google Earth and open source image processing software to hunt for interesting structures in remote regions of the planet. She regularly posts her results on the arXiv and we’ve discussed several of them on this blog, here for example.

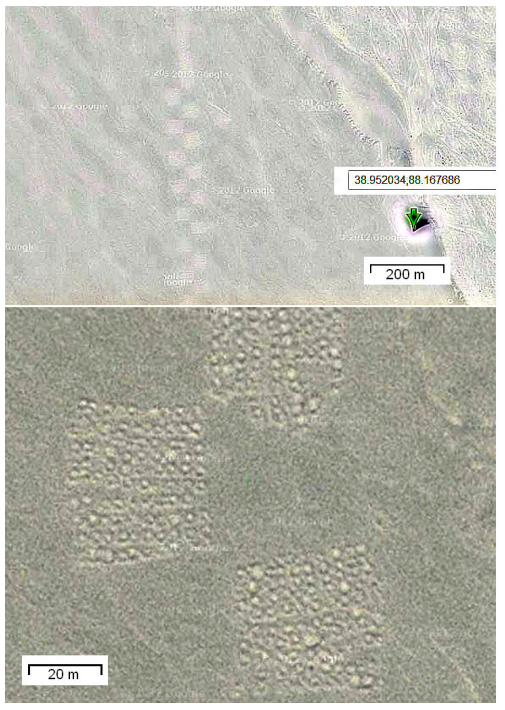

Today, Sparavigna highlights an 8km line of dots in the Taklamakan desert near Ruoqiang Town. When she zooms in on these dots, they turn out to be 40 metre grids of faint point-like structures, arranged in a chess-board-like style.

Google Earth’s images data back to 2004 and the grids are visible in all the images. However, Sparavigna points out that the grids are not visible in older images on Bing Maps or Nokia maps. In this way, she has been able to date them.

At first sight, it’s hard to work what this structure could possibly be for. But Sparavigna says she has recently discovered a clue in the form of an announcement by the Chinese government of the discovery of a 1.28 million nickel ore reserve in the region.

She says the grid is the result of a comprehensive geological survey of the region. This process begins with the identification of a geological anomaly associated with the ore, then the widespread digging of trenches and boreholes to identify the ore and map it. It is this second stage that have produced the grids.

That sounds like a reasonable explanation although the sheer number of boreholes dug over such a wide area beggars belief.

One possibility is that there was some element of training involved in which large numbers of students practiced their surveying techniques in the desert.

However, wouldn’t we be able to see the results of similar exercises elsewhere in China or indeed in other places on Earth?

Sparavigna says that if she is right, this region of China is likely to become an important centre for mining in the next few years.

That means her form of armchair archaeology can be used to determine not only what the planet was like in the past but also get a sense of what regions will be like in future.

Of course, her analysis may also be wrong. Alternative suggestions in the comments section please.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.