Stem Cells Reveal Defect in Parkinson’s Cells

Stem cells in the brains of some Parkinson’s patients are increasingly damaged as they age, an effect that eventually diminishes their ability to replicate and differentiate into mature cell types. Researchers studied neural stem cells created from patients’ own skin cells to identify the defects. The findings offer a new focus for therapeutics that target the cellular change.

The report, published today in Nature, takes advantage of the ability to model diseases in cell culture by turning patient’s own cells first into so-called induced pluripotent stem cells and then into disease-relevant cell types—in this case, neural stem cells. The basis of these techniques was recognized with a Nobel Prize in medicine last week.

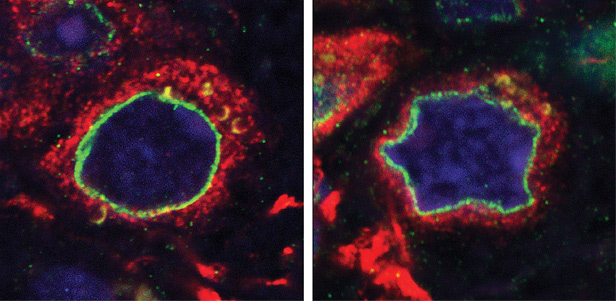

The authors studied cells taken from patients with a heritable form of Parkinson’s that stems from mutations in a gene. After growing several generation of neural stem cells derived from patients with that mutation, they saw the cell nuclei start to develop abnormal shapes. Those abnormalities compromise the survival of the neural stem cells, says study coauthor Ignacio Sancho-Martinez of the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, California.

Today’s study “brings to light a new avenue for trying to figure out the mechanism of Parkinson’s,” says Scott Noggle of the New York Stem Cell Foundation. It also provides a new set of therapeutic targets: “Drugs that target or modify the activity [of the gene] could be applicable to Parkinson’s patients. This gives you a handle on what to start designing drug screens around.”

The strange nuclei were also seen in patients who did not have a known genetic basis for Parkinson’s disease. The authors suggest this indicates that dysfunctional neural stem cells could contribute to Parkinson’s. While that conclusion is “highly speculative,” says Ole Isacson, a neuroscientist at Harvard Medical School, the study demonstrates the “wealth of data and information that we now can gain from iPS cells.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.