Silicon Valley Dynasty Adapts to Fast-and-Cheap Startups

If there is blue blood in Silicon Valley, it runs through the veins of Adam Draper. As a fourth-generation member of venture capital’s greatest dynasty, he has a curriculum vitae that includes getting bounced on the knee of investing legends like William Henry Draper III, his grandfather.

Adam is now 26, a dropout from his senior year of college and part of a new entrepreneurial generation for whom everything runs faster and a little looser. That explains why, when I was about to press “Send” on a story about his latest venture—a fascinating challenge to the venture capital industry his family helped to build—he did a pivot on me.

He wasn’t doing that business anymore. He’s doing something else.

“Sorry,” he wrote me in an e-mail. “This moved fast.”

When I first met with Draper about a month ago, at Red Rock Coffee in Mountain View, it was to discuss BoostFunder, the online matchmaking platform for startup companies and investors he’d cofounded this year. The idea is that Web and mobile startups are getting so much cheaper to launch they don’t need traditional venture capitalists anymore—at least not early on. His website, a kind of online directory, would let wealthy investors scroll through a list of young companies.

The story was appealing, as much for its oedipal family dimensions as for the lessons it held about the venture-capital industry. As Draper told me, “I’d love to be known for democratizing the funding of startups—making it so cheap to start a company that anyone can do it. In a way, it wrecks my grandpa’s and my dad’s models if that works, but I think that’s a good thing for the future of entrepreneurship.”

Venture capitalists have earned low returns over the last decade, and entrepreneurs seem to need VCs less and less. Some people are talking openly about the death of the industry (see “Fred Wilson on Why the Collapse of Venture Capital is Good”). BoostFunder would join other sites, such as AngelList (see “Venture Capital, Disrupted”), in helping to ease venture-capital firms out of the picture—at least at the earliest stages of investment, when financing needs are lower. Adam’s startup seemed to be a case in point. He’d spent less than $50,000 on it.

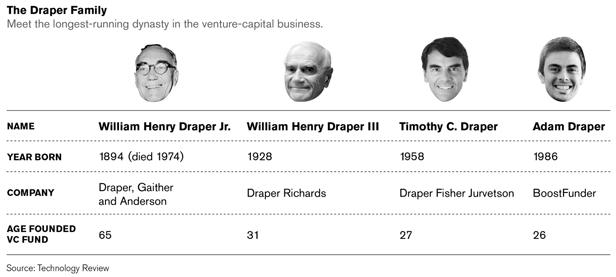

The Draper family has made a tradition of getting ahead of industry trends. Adam’s great-grandfather founded the first West Coast venture-capital firm in 1959, back when technology investments were still known as “special situations.” His grandfather Bill Draper made fortunes as an early backer of Internet telephony and heart defibrillators. His father, Tim, is the founder of Draper Fisher Jurvetson, a venture-capital firm whose exploits include establishing an investment network in China, India, and Brazil when most firms still ignored emerging markets.

The older Drapers aren’t oblivious to the transformation of their industry. There is more competition for deals, especially early-stage ones. It’s getting harder to make 1,000 times your money, as Bill Draper once did after tracking down some Estonian programmers and presenting them with a check (the company was Skype). Draper Fisher Jurvetson is now making an effort to rise above a crowded field. The firm recently hired its first head of marketing and took on a full-time partner whose job is to help portfolio companies recruit employees, managing director Josh Stein told me.

That’s not to say there weren’t some red flags about BoostFunder. You could tell by looking at the hundred-plus companies on the site that these startups were a mixed bag—zeitgeisty fun stirred with a dash of serious innovation. One company looking for attention was Dareme.to, a Kickstarter for “dares,” whose mobile app would let people pool money to encourage friends to do something crazy.

When I had asked Bill Draper, who at age 83 is the dean of Drapers and still a general partner at his firm Draper Richards, what he thought of his grandson’s site, he’d hedged his answer: “It’s very good. Well, actually, I can’t say it’s very good yet. But it’s very promising.”

Then there was the question of how BoostFunder would make money. The service was entirely free. A little belatedly, I realized this could be a problem. It’s when I asked Adam about the business model that I learned about the pivot.

BoostFunder wasn’t going to work, Draper said, because to make money on transactions it would need a financial license—a regulatory headache that he didn’t want to deal with and that would involve “making product sacrifices.” But he’d had a new idea, and had gone to his father’s offices at Draper Fisher Jurvetson in late August to discuss it. “I called my dad. He said, ‘I love it, let’s meet up,’ and we talked it through,” says Draper. They hammered it out then and there, and then he called his grandfather to pitch it to him. And that was that.

BoostFunder would now be a startup incubator instead.

“I realized that my true value is the ability to help startups get going, and I love that side of the business. In short, I’m going to be starting an incubator using BoostFunder as a name and leveraging the three generations of Draper who help build companies,” Draper e-mailed to say.

The new model is a lot like the successful incubator Y-Combinator (see “The Startup Whisperer”). Draper’s operation plans to take equity stakes in 10 to 15 young companies in exchange for providing coaching, connections, and $10,000 to $20,000 in funds, money raised from Draper’s “friends and family.” He wants the incubator to become the next logical step for startups that grow out of university entrepreneurship programs, a sort of gateway between his peer group and venture capitalists—what he calls a “bridge to Silicon Valley.” (Draper himself is at a similar juncture: he’s just finished up his last class at UCLA to earn his diploma.)

Draper had just shown me why venture capitalists—even if they’re your relatives—still have a role. It’s not easy to pull the plug, or change your whole model, without advice. There’s plenty of evidence that companies that go with name-brand investors like Tim Draper do better. Now I was seeing why. Adam Draper says his dream is to “spread entrepreneurship.” Even in a world of fast, cheap startups, that’s still done the old-fashioned way: with cash and connections.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.