Should the Government Support Applied Research?

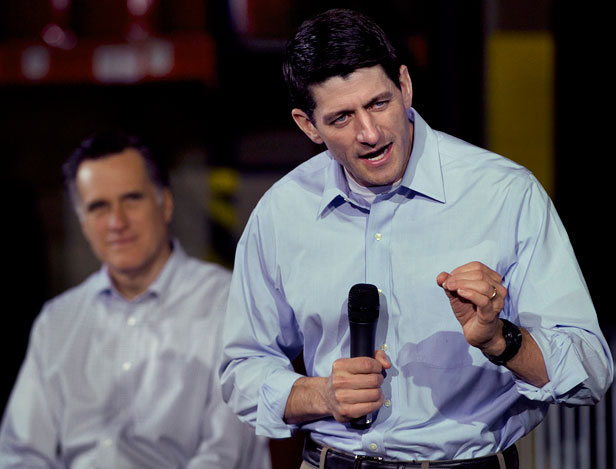

Republican criticism of federal government efforts to fund new energy technologies has spilled over to ARPA-E, the U.S. Department of Energy’s popular program for backing high-risk innovations in energy. Paul Ryan, now the Republican nominee for vice president, voted last year to slash ARPA-E’s budget, and presidential candidate Mitt Romney’s energy plan says the program should shift its focus.

Such views could rule out giving money to companies like Envia Systems, a 35-person startup located in Newark, California. Following a $4 million grant from ARPA-E, it says it’s within sight of commercializing a high-capacity energy storage technology that would cut prices for electric-car batteries in half.

“Venture capital funding took us half the way there, and the ARPA-E funding took us all the way there,” CEO Atul Kapadia says.

The presidential campaign has revived the long-running policy debate over what role government should play in funding the development of new technologies. While almost everyone believes that it has a role in supporting basic research, the consensus breaks down at later and more expensive stages of development, such as demonstration projects. Historically, some Republicans have picked fights to keep agencies from giving grants for early-stage product research, a line that ARPA-E crossed intentionally when it was created in 2007.

ARPA-E has funded around 200 projects, all of them meant to be “transformative” ways to either help replace foreign oil or reduce emissions. The notion is that such projects are too speculative and risky to gain large investments from companies. “I think it’s hard to argue the types of investments that ARPA-E is making would be made by the private sector if ARPA-E did not exist,” says Greg Nemet, an assistant professor of public affairs and environmental studies at the University of Wisconsin.

The agency, which had a modest budget of $180 million in 2011, has many fans in Congress, including among Republicans. That means it could avoid cuts and may see its budget increase. However, last year some House members said the agency should be defunded because its projects are too commercial and sometimes replicate work already paid for by the private sector.

Critics claim one problem is that ARPA-E isn’t able to find enough research that is truly transformative. Eric Toone, the agency’s principal deputy director, calls the debate over spending a “worthy” one, but says most people agree ARPA-E is funding technologies at stages where there is a “legitimate role for public investment.”

“Are we going to run out of great ideas?” he asks. “If we keep collecting the best and brightest people of America, there’s lots to do here and there’s lots of good ideas.”

ARPA-E grants are meant to help move research ideas to the prototype or demonstration stage. Projects are given specific performance goals—such as increasing how much energy can be stored in a battery—that, if achieved, would take technology a few steps beyond the best commercial products. It has financed projects such as making liquid “electrofuels” directly from microörganisms fed electricity, chemicals, and carbon dioxide, as well as a flying wind turbine (see “Flying Windmills”) and new materials to capture carbon from coal plants.

At the agency a team of scientists actively manage research programs. It’s not uncommon for them to pull the plug if technical milestones aren’t met. Such failures are partly by design. Grants are kept small (on average, about $3 or $4 million each)—part of an approach designed to pull a few winners out of a large pool of attempts.

While ARPA-E has generated a share of exciting projects, it does have one clear flaw: a lack of end customers. “The big problem that makes energy different from most other startup enterprises is that even if you have something that works great, you probably never amass enough money to commercialize it,” says Donald Paul, executive director of the University of Southern California’s Energy Institute and former chief technology officer at Chevron.

That’s where the Obama administration ran into trouble. The DOE tried to help some technologies toward large-scale commercialization, but after the bankruptcy of solar-panel maker Solyndra (recipient of a $535 million DOE loan guarantee), Republicans jumped in, accusing Obama of playing politics with technology. It’s become a campaign talking point: Ryan’s website calls for “getting Washington out of the business of picking winners and losers in the economy,” including the energy sector. Although Romney has praised ARPA-E, he’s echoed the Republican concerns by saying the agency should step back and concentrate on “basic research.”

Such a shift would be at odds with ARPA-E’s current grant portfolio. More than a third of the agency’s grants have gone to companies (the rest go to universities and government labs), and nearly all of them are for applied research projects.

In the case of Envia, the company used its ARPA-E grant to finish development of an anode design for its prototype commercial battery pack. That wasn’t basic research: there was a clear commercial goal. “It shortened our development time by two years,” says Kapadia.

Envia Systems may never get its novel battery technology into vehicles. But it stands a better chance because of its ARPA-E funding. After seeing Envia’s prototype batteries, General Motors invested $7 million in the startup. During a meeting with employees last month, the automaker’s CEO, Dan Akerson, said the battery technology could be a “game changer” for GM, judging that it stood a “better than 50-50 chance” of leading to an electric car capable of going 200 miles on a charge.

He then gave what might be the perfect endorsement of ARPA-E. “These little companies come out of nowhere,” said Akerson. “And they surprise you.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.