Twitter Mischief Plagues Mexico’s Election

The top contenders in Mexico’s presidential campaign are engaged in a Twitter spam war, with armies of “bots” programmed to cast aspersions on opposing candidates and disrupt their social-media efforts. This large-scale political spamming could foreshadow online antics that campaigners may increasingly resort to in other countries.

Twitter has been especially prominent in Mexican political theater this year as the country prepares for general elections on July 1, when citizens will elect a new president and fill a number of national and state leadership positions. One reason is that even before the election, Mexicans were frequently turning to the service as a source of information about events in northern areas of the country, where fear of violent retribution prevents news outlets from reporting about drug cartels, says Andrés Monroy-Hernández, a researcher at Microsoft Research who has been closely studying Mexican Twitter usage.

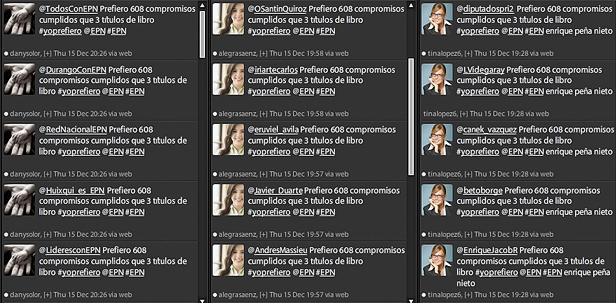

More surprising has been the degree to which campaigners are resorting to spam tactics. In the presidential campaign, one party in particular (the Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI) has come under fire for unleashing tens of thousands of bots, or user accounts programmed to automatically tweet specific words and phrases, and organizing large groups of human Twitter users to simultaneously publish the exact same message. The goal: to make it more likely for the message to land on Twitter’s list of “trending” topics.

The spamming often makes use of hashtags—words and run-on phrases preceded by a pound sign (like #thishashtagexample). Twitter users can apply hashtags to their tweets to make them easily searchable, a strategy that has proved useful for groups like the Occupy Wall Street protesters.

The PRI’s candidate, Enrique Peña Nieto, who enjoys double-digit leads in most polls, has been both the target of hashtag organization and a possible beneficiary of hashtag mischief. During the spring, an anti–Peña Nieto hashtag emerged—”#YoSoy132” (“I am 132”)—after his campaign and some major news outlets claimed that protesters at a campaign event at a university in Mexico City were not really students and had been planted by opposing parties. In response, 131 students who claimed to have attended the event posted a video on YouTube in which they showed their student IDs and lashed out at media coverage. The video launched a movement centered on the hashtag and variations of it, all of which imply that its user is the figurative 132nd protester. Before long, however, Peña Nieto supporters were coöpting that hashtag, as they have done with many others, and adding it to messages that praised or promoted him, Monroy-Hernández says.

All three dominant political parties have used bots in various elections at the national and state level, though the PRI is the only party that is “without a doubt” using them in the presidential campaign, according to Iván Santiesteban, a Web developer in Monterrey, Mexico, who has created a site where people can report spam accounts—information that can eventually be passed to Twitter. Santiesteban, who has devised a simple automated method for detecting bots, says he’s found and reported 18,000 so far. But with or without bots, all three big parties have “deployed their young supporters to social networks,” Santiesteban says, and “sometimes it’s hard to tell if what they are doing is honest political activism or spam.”

Reports of similar politically motivated spamming have appeared in other countries, including Russia, Syria, and the United States. For its part, Twitter states clearly that spam is against its rules, citing 20 separate examples of behaviors it considers to be spamming.

Meanwhile, the company’s engineers are constantly trying to “proactively reduce spam,” says spokeswoman Rachael Horwitz. For instance, Twitter collects data that could reveal malicious or abusive activity. It also recently filed a lawsuit in the U.S. against “five of the most aggressive” spammers and providers of spamming tools. But the company also admits in its terms of service that this is bit like an arms race: “What constitutes spamming will evolve as we respond to new tricks and tactics by spammers.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.