Use Their App, Keep Your Data

Ever noticed that so many apps need access to your contact lists, browser history, location, and other personal data? As part of a fight back against this data-gobbling trend, a Bulgarian software developer has rewritten the Android operating system so that it gives apps bogus data.

Under the radical rebuild of the mobile operating system, you still click to grant apps permission to access your data, but the apps don’t get the real stuff. For bookmarks, it provides default ones that came with the device (such as www.google.com). For logs—which can store all sorts of data—and phone contacts, it simply returns empty ones.

“I don’t like applications accessing my location or phone book,” says the developer, Plamen Kosseff, who by day writes code for a software company, ProSyst, in Sofia, Bulgaria. “Why should they be accessing my phone book to see data I have from other people?”

Kosseff’s custom OS is part of a research trend toward giving users more control over how apps deal with their personal data in the wake of major leaks and revelations such as last year’s Carrier IQ controversy, in which an obscure piece of network-diagnostic software on 141 million phones was revealed to have the ability to transmit personal information.

On Thursday, NQ Mobile, a mobile security firm, formally released its mobile vault app, which provides a password-protected, encrypted part of your phone for storing sensitive data. Apps can access only the devices’ default contact list, for example, not the one you’ve put in the “vault.”

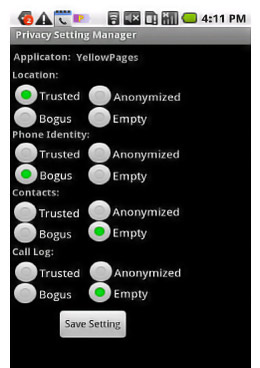

Xuxian Jiang, a security researcher at North Carolina State University, and colleagues are working on an application, still in the research stages, that’s a little more nuanced than Kosseff’s. Called “taming information-stealing smartphone applications,” or TISSA, it gives users more control over the information apps can access.

The app would allow you to decide which information to share—like a phone’s unique ID number, contacts, and location. Then, for each type of data, you’d have four versions you could give an app: “trusted” (the actual information), “bogus,” “anonymized,” or simply “empty.”

“Basically, we could allow users to customize in a fine-grained manner what data will be available to a particular app. Maybe if you are in a sensitive conference meeting, you don’t want an app to see your location,” Jiang says.

The team’s application has not yet been deployed. To work, it requires control over other apps, and this kind of power can be implemented only through a change in the operating system—a task Jiang is hoping device makers will help with.

“Eventually, we will come up with ways to protect data. Some protection may be possible from third-party apps, but many will require OS support, and this might mean engaging with vendors. It’s a tough question to say when this will happen,” Jiang says. “Smart-phone vendors, if they like the idea, they can implement similar customization, but they have not adopted this approach yet.”

In the meantime, it falls to people like Kosseff to implement solutions. A fresh build of his Android revision was uploaded here on Thursday, with the added feature that gives empty phone book data, an addition to earlier versions that gave default bookmarks and empty history and Android logs.

Right now the software works only for the HTC Desire HD, though Kosseff says simple revisions would make it work on Samsung and other Android phones. He is looking for other developers to expand its applicability.

Kosseff initially tried to implement his changes through an existing project called Cyanogenmod—an aftermarket version of Android with myriad new features like custom interfaces and extra security. However, leaders of that project declined the offering, Kosseff says, over concerns that if Cyanogenmod became too hostile to apps, app developers would merely add something to their code to make an app unusable on devices running Cyanogenmod.

Kosseff says he does not know how many people may have downloaded his version. Most of his changes within Android were made to PackageManager, the part that handles installing and removing applications and their associated permissions. Others were made to portions called providers, which Android uses to deal with specific data like the bookmarks and logs.

For any such tool, usability is a key concern. Jiang points out that the harder it is for Android owners to learn about and implement any new technology to protect their data, the less likely it is they will bother.

And even if they do install it, the resulting software must be intuitive to navigate. “We have to strike a balance between the security and usability of the phones,” Jiang says.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.