The Future of Medical Visualisation

Medical visualisation is the use of computers to create 3D images from medical imaging data sets. It’s a relatively young field of science, relying heavily on advances in computing for its horsepower.

Despite its youth, these techniques have revolutionised medicine. Much of modern medicine relies on the 3D imaging that is possible with magnetic resonance imaging scanners and computed tomography (CT) scanners, which make 3D images out of 2D slices. Almost all surgery and cancer treatment in the developed world relies on it.

So an interesting question is where medical visualisation will take us next. Today, Charl Botha at the Leiden University Medical Center in The Netherlands, and a few friends take a short tour of the history of medical visualisation and throw some light on the future of this fascinating field.

Perhaps the most important factor in medical visualisation is the way the data is taken and here there are numerous advances in the pipeline.

In the last five years, commercial CT scanners have become available that can take five 320 slice volumes in a single second. That’s fast enough to make 3D videos of a beating heart.

There are also various new diffusion imaging techniques which reveal the diffusion of water through the body. That’s important because water tends to follow otherwise hard-to-image structures such as nerve bundles and muscle fibres. Images of these structures is opening important new areas of study in neuroscience and biomechanics.

Then there are the imaging techniques that work on the level of molecules and genes. The great potential of these is that they can reveal pathological processes at work long before they become apparent on the larger scale, in the form of tumours, for example.

Collecting the data is just one part of the challenge, of course. Representing it visually in a way that allows the most effective analysis is also hugely difficult but again there have been huge advances.

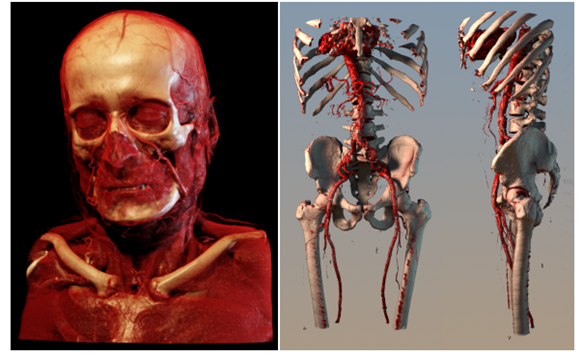

One of the most spectacular is the representation of medical data topologically, in other words showing the surfaces of objects. That makes it possible to more easily see the shapes of organs and to plan interventions such as surgery.

What’s more, the most recent image processing techniques allow the addition of realistic lighting effects creating photo-realistic images. Beyond this, hyper-realistic images can show what lies beneath certain layers. The images at the top of this page are recent examples of this.

These kinds of images are crucial for reconstructive surgery but a huge challenge for the future and the subject of much current research, is to create images of the potential outcome of interventions that show the result of the surgery.

Another area of growing importance is the visualisation of multi-subject data sets. The idea here is to take images of a particular condition from lots of different patients and to combine them in a way that shows the progression of the disease or how it varies between different population groups, for example. Clearly, the challenges here are manifold.

The final piece in this puzzle is the way medical practitioners view images and once again this is changing rapidly. The technology driving this change is essentially the iPad.

It’s easy to forget that this device hit the shops only in 2010, practically yesterday in the timeline of medical visualisation technology. And yet it has already transformed the way many doctors access and interact with images, not least because it frees them from desk-based computers.

Of course, there are various issues with privacy but it’s fair to say that the future of medical visualisation is firmly tied to slate-type devices.

One area that Botha and co do not cover in their future is the cost of these imaging techniques and how they can be made cheaper. That’s an unforgivable omission but perhaps a reflection of the narrow focus of medicine in the 21st century .

Many of the techniques Botha and co describe are available only to the richest 1 per cent or so of the world’s population. For the other 99 per cent, these techniques are essentially science fiction.

That’s clearly unacceptable. The biggest challenge of all is to find ways of making powerful medical visualisation techniques cheap enough for everyone.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1206.1148: From Individual To Population: Challenges In Medical Visualization

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.