Drugs made of protein have shown promise in treating cancer, but they are difficult to deliver because the body usually breaks down proteins quickly.

To get around that obstacle, a team of MIT researchers has developed a new type of nanoparticle that can synthesize proteins on demand. Once these “protein factory” particles reach their targets, the researchers can initiate protein synthesis by shining ultraviolet light on them.

The particles could be used to deliver small proteins that kill cancer cells and, eventually, larger proteins such as antibodies that trigger the immune system to destroy tumors, says Avi Schroeder, a postdoc in MIT’s David H. Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, who developed the particles with Institute Professor Robert Langer, ScD ’74, and Daniel Anderson, an associate professor of health sciences and technology and chemical engineering.

The researchers hope to use the protein-building particles to attack tumors that have spread from the original cancer site to other parts of the body. Such metastases cause 90 percent of cancer deaths.

The particles mimic the protein-manufacturing strategy found in nature. Cells store their protein-building instructions in DNA, which is then copied into messenger RNA. That mRNA carries protein blueprints to cell structures called ribosomes, which read the mRNA and translate it into amino acid sequences. Amino acids are strung together to form proteins.

“We wanted to use machinery that has already proven to be very effective,” says Schroeder. “Ribosomes are used in nature, and they were perfected by nature over billions of years to be the best machine that can produce protein.”

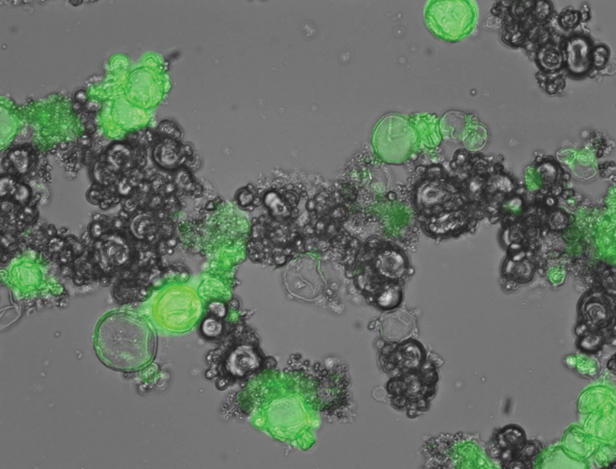

The nanoparticles contain a mixture of ribosomes, amino acids, and the enzymes needed for protein synthesis, all carried in a fatty outer layer. Also included in the mixture are DNA sequences for the desired proteins. The DNA is trapped by a chemical compound called DMNPE, which temporarily binds to it. When exposed to ultraviolet light, the compound releases the DNA, allowing the researchers to control when and where proteins are assembled.

The team is now investigating other ways to trigger protein production. For example, the DNA might be released when the particles encounter a particular acidity level or other biological conditions specific to certain body regions or cells.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.