How to Get Everyone To Secure Computers

If you want to get your malicious software loaded on 1,000 U.S. computers, it will cost you about $100, or a dime each, on the black market. Getting your malware on 1,000 machines in Asian countries will cost you only $5.

These infected computers—collectively known as botnets—can be used to send spam, steal passwords or other private information, and hack into corporate computer systems. Researchers estimate that five million computers around the world were infected just in the first quarter of 2012.

With infections perennially hard to stop, especially on computers with outdated software or lacking in antivirus protection, one key front in the war against botnets involves enlisting millions of average people—hapless owners of infected computers—to take action by cleaning their machines and keeping them up to date. Even if the government or industry wanted to bypass these users, it couldn’t, because in the United States, and many other places, private machines can’t be touched without a court order.

“There is a fundamental conundrum in the fact that we can identify literally millions of compromised machines that we are not in a position to do much about with regard to cleanup,” says Stefan Savage, a computer security researcher at the University of California, San Diego.

Last week, the White House and major computer and Internet companies that make up the Industry Botnet Group—a partnership formed last year—pledged to step up industry action against botnets. The new effort includes increased coöordination between industry and government, progress toward information sharing between Internet service providers and financial institutions, and a Keep a Clean Machine campaign to step up consumer education. All of this is voluntary.

There is wide acknowledgment, however, that a crucial problem is figuring out how to persuade technologically naïve and apathetic users to protect themselves. Efforts to study what sorts of warnings actually trigger productive action by computer owners is one part of that approach. And ISPs will play a key role, since they are the natural point of contact with computer users.

“Botnets today are where spam was in 2004, when we thought spam would sink the Internet, or at least e-mail,” says Michael O’Reirdan, a Comcast executive who is cochairman of an industry group that, among other anti-abuse efforts, tries to improve how ISPs notify people and help them fix their machines.

ISPs eventually took a leading role in fighting spam by hiring technical staff and creating filters to catch junk messages. But their efforts to combat botnets by notifying computer owners of infections are still primitive—“like DOS 1.0,” as O’Reirdan put it, referring to Microsoft’s original 1980s operating system.

Attempts to understand how consumers might be persuaded to take a more active role in securing their machines have followed law-enforcement agencies’ recent hijackings of major botnets. Last November, the FBI hijacked DNS Changer, a botnet that redirected people to infected websites, and arrested those involved. The FBI no longer allows the redirections, but it can still see the flows of requests coming in to DNS Changer, and therefore how many active infections are still out there—350,000 at last count.

This kind of information will help ISPs determine what kinds of alerts and messages prompt people to take action, says O’Reirdan. The ISPs can see changes at specific times and from specific geographic areas in traffic flowing to DNS Changer. “This will be the first time we’ve had a population where we’ve done some of this correlation and research,” he says. No findings are yet available.

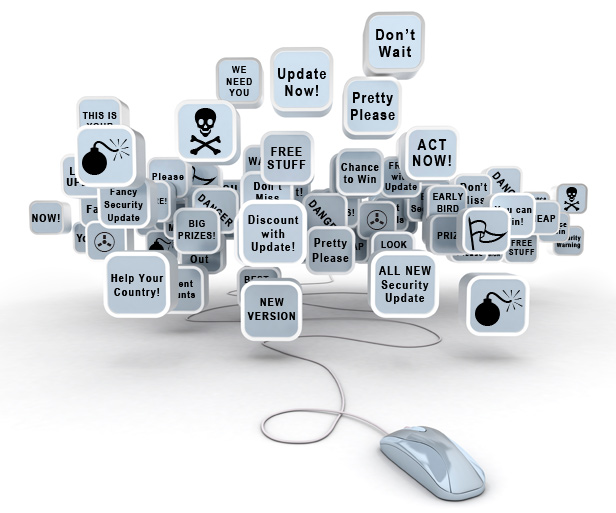

Paradoxically, compounding the problem is that “people have been trained not to click on e-mails or pop-ups they don’t understand because it might be a phishing attack—but how else do you contact your customer? We have to start somewhere,” O’Reirdan says.

It’s also proving difficult for software companies to have an impact. Last year, Microsoft played a leading role in shutting down the command-and-control servers of another botnet, called Rustock, in a civil action. But only 58 percent of machines infected in the United States are thought to have been cleansed of the actual virus.

“All of these operations mean little if you don’t get to the victims,” says Richard Boscovich, senior attorney for Microsoft’s Digital Crimes Unit. “That’s one of the cornerstones—notifying the victims and stopping the continued victimization.”

A surprising number of people have switched off automatic updates for their operating systems and have no antivirus software installed, Boscovich adds. (Software companies cannot change things on people’s computers unless the user gives permission in advance.) Users of Microsoft operating systems can visit this site to learn how to use Windows Update; other security information is available here.

To take Rustock down, Microsoft got court orders to seize botnet-related Web addresses and servers. While efforts like this one are helpful, they do little to change the business model of botnets. And while the tools in the fight against malware have gotten a lot better, Savage says, they have not gotten good enough to change the game.

“The fact of the matter is that compromising large numbers of machines is still easy,” Savage says.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.