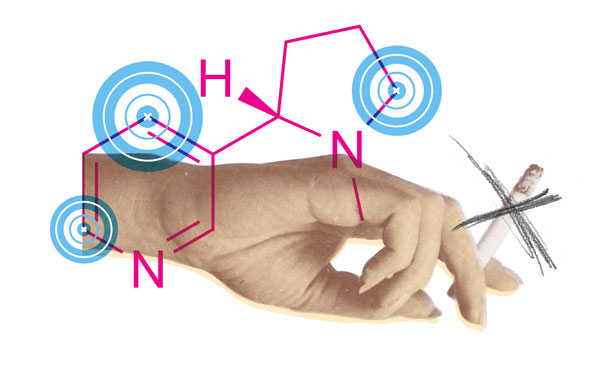

Vaccine Could Stop Nicotine from Reaching the Brain

A Boston-area startup is pursuing an unorthodox approach to helping smokers quit—it’s attempting to make the world’s first successful nicotine vaccine.

The company, Selecta Biosciences, was cofounded by MIT engineer Robert Langer and Harvard immunologists Ulrich von Andrian and Omid Farokhzad. Its goal is to develop a treatment that deprives a smoker of the habit’s addictive effects by inducing an immune response that can last several years.

While nicotine is not a virus, it can be targeted in the same way a virus is targeted, Langer and his colleagues believe. Selecta uses synthetic nanoparticles to prompt the immune system into creating specialized antibodies that bind to nicotine molecules, making the nicotine molecules large enough to initiate an immune response. Antibodies instigated by the nanoparticles automatically attach to the surface of the modified nicotine molecule because their shape fits exactly. The resulting supersized nicotine compound is thereby prevented from crossing the blood-brain barrier and delivering the normal smoking kick.

In the past year, Selecta’s nanoparticles have been tested in the lab; now the company is testing the safety of the nanoparticles in people, in a Phase I trial.

Selecta’s nicotine vaccine is the most advanced example of its effort to make custom vaccines with engineered nanoparticles. These synthetic vaccines should be quicker to make in large quantities than conventional vaccines, and therefore cheaper. Selecta also hopes to develop immune-based treatments for ailments and illnesses, including malaria, that currently lack such treatments.

Since Selecta’s approach removes nicotine before it can cross the blood-brain barrier, it differs from other smoking aids, which interfere with the craving for cigarettes by delivering nicotine in another manner, such as a patch.

Even though Selecta’s vaccine has no biologically based equivalent drug to compete with, it nevertheless will have to overcome plenty of hurdles. To be considered effective in clinical trials, the treatment will have to cause some people to quit altogether, rather than simply reducing their smoking.

The nicotine vaccine does not eliminate the craving for nicotine—instead, it diminishes the effect from smoking the cigarette. As a result, smokers who are given the vaccine will find that they can’t alleviate their nicotine withdrawal symptoms by smoking. Selecta’s vice president, Peter Keller, acknowledges that smoking several cigarettes in a row could overwhelm the immune system to render partial pleasure, since enough free-flowing nicotine molecules would still pass through uninhibited to the brain.

Previous efforts to make a smoking vaccine were based more on the conventional approach of delivering nicotine in a less harmful way, but they weren’t successful at getting people to stop smoking.

Existing drugs have severe side effects and are largely ineffective at getting people to quit. Chantix, a type of antipsychotic drug that blocks nicotine from binding with receptors once nicotine has entered the brain, has a smoking cessation success rate below 25 percent, but it has made over $700 million in worldwide sales per year since its release in 2007.

A nicotine vaccine should also work for several years. Nicotine drugs like Chantix or Zyban, in contrast, stop working once the treatment ends, and such drugs can’t be used longer than several months because of their severe side effects.

Selecta has raised almost $80 million from venture capital firms Polaris, OrbiMed, and Flagship Venture Partners, as well as from the Russian government through its $10 billion biotech investment fund Rusnano. Keller says that preliminary Phase I results could come as early as July, at which point that trial will either expand, if the results are inconclusive, or continue to Phase II if the nicotine-binding nanoparticle is well-tolerated in humans.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.