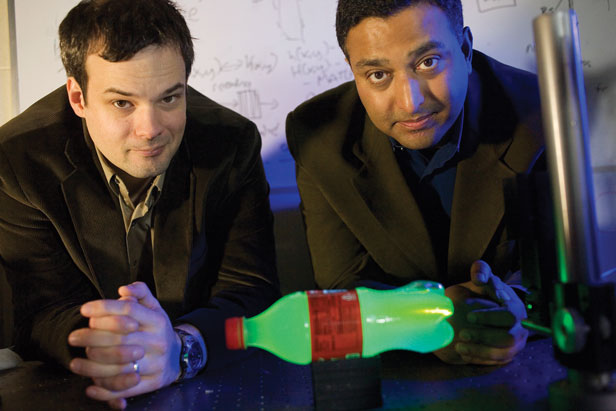

MIT researchers have created a new imaging system that can acquire visual data at an effective rate of one trillion exposures per second—fast enough to produce a slow-motion video of a burst of light traveling the length of a plastic bottle. “There’s nothing in the universe that looks fast to this camera,” says Media Lab postdoc Andreas Velten, one of the system’s developers.

The system relies on a technology called a streak camera, whose aperture is a narrow slit. Particles of light—photons—enter the camera through the slit and are converted into electrons, which pass through an electric field that deflects them in a direction perpendicular to the slit. As a burst of light travels through a plastic bottle, some of its photons exit the bottle all along the way; the camera captures where those photons exit. Because the electric field is changing very rapidly, it deflects the electrons corresponding to late-arriving photons more than it does those corresponding to early-arriving ones. The camera can thus determine the time of arrival of photons passing through a one-dimensional slice of space.

To produce their super-slow-mo videos, Velten, Media Lab associate professor Ramesh Raskar, and chemistry professor Moungi Bawendi must perform the same experiment—such as passing a light pulse through a bottle—over and over, continually repositioning the streak camera to acquire a new one-dimensional sample of the scene. It takes only a nanosecond—a billionth of a second—for light to scatter through a bottle, but it takes about an hour to collect all the data necessary to build up a two-dimensional image for the final video. For that reason, Raskar calls the new system “the world’s slowest fastest camera.”

After an hour, the researchers have accumulated hundreds of thousands of data sets, each of which plots the one-dimensional positions of photons against their times of arrival. Raskar, Velten, and other members of Raskar’s Camera Culture group at the Media Lab developed algorithms that can stitch the raw data into a set of sequential two-dimensional images.

Because the system requires multiple passes to produce its videos, it can’t record events that aren’t exactly repeatable. Any practical applications will probably involve cases where the way in which light scatters—or bounces around as it strikes different surfaces—is itself a source of useful information. Those cases may, however, include analyses of the physical structure of both manufactured materials and biological tissues—“like ultrasound with light,” as Raskar puts it.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.