The Professor Who Brings Physics to Life

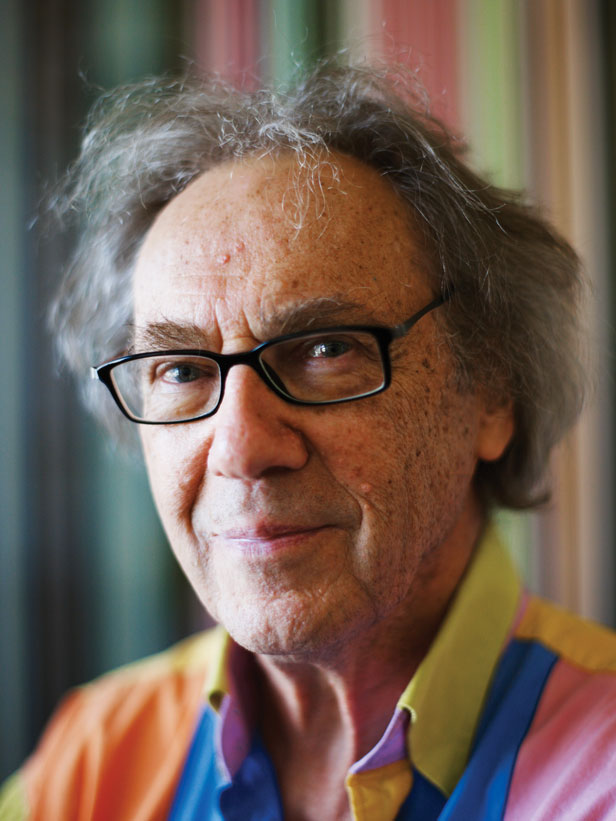

For the past four minutes, Walter Lewin has been laboring at the chalkboard, bent on conveying a point—or rather, a series of small, swift points, so close together they resemble a perforation. The 76-year-old professor emeritus of physics is demonstrating a curious phenomenon, although the topic is not Newton’s laws or Maxwell’s equations but something arguably more befuddling.

“The idea is that the chalk should not be too short,” Lewin instructs his student. “You have to push on the board, and if you don’t push too hard, it will jump. If you go a little faster, then you’re in business.”

The student takes another literal stab at the board, trying to imitate the rapid trajectory of dots that Lewin is known for drawing seemingly effortlessly with a sweep of the arm, producing a sound akin to tiny machine-gun fire.

How he draws these dotted lines is a question Lewin receives on a regular basis from fans all over the world. Each year, nearly two million people find the wiry-haired professor through YouTube, iTunes U, and MIT’s OpenCourseWare—not only sketching out equations but swinging from a pendulum, smoking handfuls of cigarettes at a time, or jumping from a desk with a gallon of apple juice, all to prove principles of physics.

See videos of Walter Lewin teaching, drawing dotted lines, and giving his last MIT lecture here.

For 43 years, Lewin taught as many as 600 students a semester in MIT’s three introductory physics courses—8.01, 8.02, and 8.03—and consistently drew rave reviews. In 1999 the Institute began videotaping the 94 lectures from the three courses, and in 2004 OpenCourseWare started posting the videos, which could be viewed free of charge by anyone with an Internet connection. The lectures soon spread to YouTube, iTunes U, and Academic Earth, and in 2007 the New York Times caught wind of the traffic, profiling the physics professor in a front-page feature as an international “Web star.”

The in-box of a Web star

Since his videos went online, Lewin has received thousands of letters and e-mails from admirers all over the Internet, including Bill Gates, who has viewed his lectures—many more than once. “I had some great teachers when I was a kid, but I wish there had been more like Lewin,” Gates writes in a review of Lewin’s new book, For the Love of Physics: From the End of the Rainbow to the Edge of Time—A Journey Through the Wonders of Physics.

Each day, two to three dozen e-mails arrive in Lewin’s in-box, many from fans with physics-related questions. Most often, people write to thank him for changing their view of physics—and the world. Lewin makes a point of answering every e-mail. He thanks his online students and volleys back meticulous explanations to physics questions, often within minutes of receiving them. He is quick to offer suggestions for supplementary materials, and once he even mailed 18 physics books in response to a plea from a boy who came from a poor family and was struggling with a hearing impairment. The boy had watched Lewin’s videos and told the professor that they changed his life, and that he fished books out of the dumpster to help him in his quest to become a doctor. “You made me love physics,” he wrote. “I believe now I have a chance in life.”

On his personal computer Lewin keeps a special file of e-mails that have had particular meaning to him over the years. The document is more than 700 pages long, but it represents just a small slice, he says, of the fan mail he’s received.

Some people hope to meet Lewin someday, and many make the trip to MIT hoping to encounter him in person. Once he accepted an invitation to visit an admirer in Seattle. Steve Johnson, then a fleet technical manager at Boeing, offered the professor a free ride on the company’s 767 flight simulator.

Johnson recalls, “My favorite part of the flight was when he shouted, ‘Steven, this is impossible! I feel the sensation of acceleration, yet I know this simulator is not moving.’ All I had to do was provide an explanation one time … a sign that he was a brilliant student.”

While Johnson had the rare opportunity to meet the professor on his home turf, other viewers are content simply to watch him on the Web. One 13-year-old girl from Chennai, India, reflected the sentiment of many in an e-mail to Lewin in 2006: “I do not feel ‘left out’ that I am not in one of the best schools. ‘The best’ of teachers is in my home.”

Connecting the dots

When fans ask for the secret to his dotted lines, Lewin simply invites them to his classroom for an in-person demonstration—the only surefire way to get the message across. In fact, he asserts that he can teach the trick to anyone in five minutes or less.

Back in his office, he retrieves the chalk from his student.

“Can I try it and see what I do differently?” Lewin asks. “You have to feel it in your fingers and let it sort of jump off the board.”

After Lewin demonstrates, the student reluctantly takes the chalk back. What if she never gets it? What if the chalk refuses to jump? But he presses on, encouraging her to try again. After nearly five minutes, the chalk jumps.

The student—this writer—must admit that the first jump was almost exhilarating, like a shot of espresso, or joy. The effort Lewin put into demonstrating and explaining was perhaps disproportionate to the triviality of the exercise, but for him, the payoff—that electric moment of understanding—is worth it.

Lewin has applied the same energy and effort to teaching physics, aiming to instill a visceral, long-lasting understanding in his students. In his final 8.01 lecture, he often told them that while they would most likely forget Kepler’s Third Law (though, he hoped, not before the final exam), they would probably remember that “physics can be very exciting and beautiful … if only you have learned to see it and appreciate the beauty.”

Seeing lessons

Walter H. G. Lewin was born January 29, 1936, in the Netherlands, and grew up amid the upheaval of World War II. In 1940, Germany seized control of the Netherlands and deported droves of Dutch citizens to concentration camps. Many of Lewin’s relatives were captured and sent to the gas chambers, a fact he still finds difficult to contemplate. In his book, he notes that his father, who was Jewish, faced increasing restrictions at the hands of the Nazis—he was banned from public transportation, public parks, and even his favorite restaurants. The cemetery was one of the few places he was allowed to frequent. One day, Lewin remembers, his father simply “disappeared,” in order to protect his family from further scrutiny by the Nazis.

Walter Sr. returned in 1944, and the family continued running the small school his parents had begun before the war. The school offered typewriting and shorthand, and when he was in college Lewin helped out as an instructor.

It was art, however, that first triggered his love of teaching. He absorbed an early appreciation of art from his parents, who owned an extensive collection of paintings. (One of his favorites was a portrait of his father that now hangs over his fireplace in Cambridge. “It’s his glasses that truly stand out: thick, black, outlining invisible eyes, they follow you around the room, while his left eyebrow arches quizzically over the frame,” Lewin writes in his book. “That was his entire personality: penetrating.”)

Lewin remembers delivering his first lecture, to his high-school peers, when he was 15: a presentation on Vincent van Gogh that he gave for a class assignment. “It must have been awful,” he recalls, “because at that age I was just looking at art, not seeing art.”

He would later draw this distinction—looking versus seeing—in his physics lectures, urging students to truly see, for example, that physics explains the order of colors in a rainbow.

“Every student of mine knows red is on the outside, and blue is on the inside, and that the secondary bow is reversed,” Lewin says. “And every time they see a rainbow, they will check that, because I have taught them how to see.”

The road to the lecture hall

In 1965, Lewin earned a PhD in nuclear physics at the Delft University of Technology, where he taught classes by day and performed research by night. He kept up a relentless, 80-hour-per-week schedule in order to “kill three birds with one stone”: by teaching for five years, he was able to pay back his loans, avoid serving in the army, and complete his degree.

After graduation, Lewin received a pivotal invitation from Bruno Rossi, a pioneer of x-ray astronomy, to come to MIT and work in the emerging field. Once on campus, he joined a team of researchers analyzing data from weather balloons for x-ray sources—evidence of far-off galaxies. Six months after he set foot on campus, MIT offered Lewin a faculty position, and as he likes to say, he never left.

Lewin dove enthusiastically into x-ray astronomy at the Institute. In 1972 he orchestrated the launch of the world’s largest weather balloon in Australia, sending an x-ray telescope to an altitude of about 45,000 meters to measure high-energy x-rays from outer space. Soon after joining the faculty, Lewin also took on the three core courses in physics, lecturing to hundreds of undergraduates in MIT’s largest lecture hall, 26-100. With his fly-away hair and penchant for large, colorful pins, he was at first a curiosity and then a perennial favorite among undergraduates, who attended Lewin’s lectures largely for his elaborate and seemingly off-the-cuff demonstrations.

At any given class, students found the professor balancing on a ladder as he sucked from a five-meter-long straw to demonstrate hydrostatic pressure; or rocketing across the stage on a tricycle powered by a fire extinguisher; or playfully thwacking a student with a pelt of cat fur to create an electric charge.

These classes may have had an air of ease and improvisation, but Lewin took great pains in assembling each lecture. He made sure to lay a foundation and provide context, combining equations and demonstrations. Each lecture was paced in a manner reminiscent of theater, complete with a buildup, climax, and dénouement.

“I can make students laugh, and I can make them cry,” he says. “I can make them sit on the edge of their seats, and I can make them stop breathing … I can build up to a drama and a tension that is almost unbearable.”

To achieve this, Lewin typically spent 40 to 50 hours preparing for each lecture, rehearsing the 50-minute production two or three times—the last on the morning of class. His lecture notes, which are preserved and proudly displayed in a series of binders on his office shelves, reveal an intense drive for both precision and drama.

For example, Lewin marked his written notes at five-minute intervals and used a large clock onstage to make sure he was on track. He also made sketches of the light panel in the hall, coloring in which buttons to push at particular points throughout the lecture. This way, he says, not a second was lost to logistics.

“Walter was half chalk talk, half demo, and total theater,” says Craig Milanesi, video production manager at MIT. “He was also very precise and demanding, like science.”

In the mid-1980s, Milanesi directed Lewin in a series of video help sessions, which the professor crafted as a supplement to his physics courses. The sessions ran every hour on MIT’s cable channel, and students gathered in dormitories to watch, often just for fun. Sitting at a desk, Lewin would speak candidly into the camera, peppering his talk with sketches, demonstrations, and personal stories. And just like his live lectures, the sessions were timed to the second.

“He could tell you, ‘I was 30 seconds over,’ or ‘I ran a minute early,’” Milanesi recalls. “He was intense, direct—a perfectionist.”

Going global

In 1999, through the efforts of Professor Richard Larson, the physics department acquired funding to videotape Lewin’s lectures. Milanesi and videographer Tom White were among the crew that completed the task over the next few years.

“We had a great rhythm going,” White says. “Because Walter was so prepared with his lectures, it was just choreographed like a dance piece.”

Several years later, when the videos went global through OpenCourseWare, White, who can be seen operating the handheld camera in some frames, would feel the ripple effects of Lewin’s fame.

“I went to a bar mitzvah, and a teacher from Chicago asked what did I do,” White recalls. “I said, ‘I work at MIT,’ and he said, ‘Oh, I use these Walter Lewin tapes,’ and I said, ‘I work on those!’ and he said, ‘Honey! He works with Walter Lewin!’”

In fact, many teachers have written Lewin over the years to thank him for his videos, which they use or refer to in their own teaching. They’re often used in less formal settings, too. Kristen McIntyre ‘80, a senior software engineer at Apple, used them to help her teenage son see the world with the joy and wonder of a scientist, often pausing the video to give a more detailed explanation or to reinforce a point. “I have fond memories of stopping, for example, to explain gyroscopes, and both of us making right-hand-rule finger signs to each other as we worked through it,” she says. “It really made the difference for him in his physics classes in high school and college, in all of which he received As. I have literally hundreds of pages of diagrams and worked problems, all of which were catalyzed by those 8.01 lectures.” Today, McIntyre keeps most of Lewin’s lectures on her iPad. “I watch them whenever I’m in the mood for a really fun jaunt back to 8.01 or 8.02,” she says.

Lewin’s uninhibited style has also had an impact on his peers at MIT. Donald Sadoway, a popular lecturer and professor of materials chemistry, credits him with helping to develop his own teaching style at a school that tends to give research, not teaching, top billing. From Sadoway’s perspective, lecturers at research universities may feel they need to be serious to be perceived as professional—a pressure that he says “is orthogonal to the notion of revealing the true personality of the individual.”

“The really good lecturers at some level are eccentric personalities in their own way,” says Sadoway. Lewin’s lectures “gave me the confidence to develop my lecturing, to not pull back, to put myself out there, knowing that Walter’s doing the very same thing in his own way.”

Lewin has rarely, if ever, been known to hold back, either in or out of the lecture hall. For example, he often stops by fountains on a sunny day to point out rainbows to passers-by. “I’m sure some of them think I’m weird,” he writes in his book. “But as far as I’m concerned, why should I be the only one to enjoy such hidden wonders?”

Joseph Goldbeck ‘07, who took 8.03 with Lewin, recalls another instance of this impulse to educate. In 2005, he went to see Lewin at a campus Hillel event and introduced himself as a former student. Lewin asked whether Goldbeck carried a diffraction grating—a plastic slide that splits light into various wavelengths, making all the colors in a beam visible. Goldbeck dug a grating out of his backpack, where he had kept it since taking Lewin’s class. The professor held it up to the light for a moment and reached into his pocket for his own. “He said, ‘This one’s no good,’ ” Goldbeck recalls. “ ’Here, have mine—it’s the best one of the batch.’ ”

Goldbeck carried Lewin’s grating for years, and often fished it out whenever he came across an interesting light source. “I think he felt with a better grating, I would enjoy the physics of light more in my life,” he says.

Beyond 26-100

Although Lewin became emeritus and retired from teaching in 2009, he still comes to his office on campus twice a week to open his mail, discuss research, read literature, and meet admirers who want to shake his hand. He receives regular requests to speak around the world and recently accepted invitations to lecture in South Korea, Washington, D.C., and the Netherlands.

Lewin also accepts friend requests on Facebook, though not without making a request of his own. For years, he held a weekly art contest outside his MIT office, challenging students to guess who had created a certain work and when. Now he posts 30 to 50 of the more than 250 works he’s featured over the years and asks potential Facebook friends to identify them. Fewer than 50 people have passed the test.

A recent visit to his office found Lewin in the midst of a move. After keeping the same office for more than 40 years, he was relocating to a smaller one down the hall, packing up the many paintings, textbooks, and mementos he’s accumulated over the years. His binders, containing the notes from every one of his 103 videotaped lectures (including some he did for children and one he gave at the University of Delft), had already been moved to the new space.

On May 16, 2011, Lewin celebrated the release of his book by taking his notes out once more to deliver one last lecture in 26-100. The hall was filled beyond its capacity with current and former students, faculty, and fans. For Lewin, that last lecture—of more than 800 he has given in the hall—was a bittersweet high.

“You know you’ve got them in your hands,” he says. “You know that you could do anything with them that you wanted. You also know in a way it’s the last time that you will do that. Then you know that it comes to an end. It’s very emotional for me. But the beauty is, two million people watch me every year. And that will only increase.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.