Fire in the Library

Until a few months ago, Poetry.com held more than 14 million user-submitted poems, some dating back to the mid-1990s. The site existed to make money: it had ads and at one point sold $60 anthologies to fledgling poets who wanted to see their work in print. But to the users, Poetry.com was much more than a business. It was a scrapbook, a chest for storing precious emotional keepsakes. And they assumed, perhaps naïvely, that it would always be there.

On April 14, the owner of the site abruptly announced that it had been sold and that every poem would be removed by May 4. “Dear Poets,” read an e-mail sent to the roughly seven million users. “Please be sure to copy and paste your poems onto your computer and connect with any fellow poets offsite.” Users who saw the notice rushed to notify their fellow poets, some of whom had not logged on in months. At 12:01 a.m. on the appointed date, all 14 million poems disappeared from public view. “Your poems are GONE,” wrote 1VICTOR, one of the site’s users. “This tells me that their intentions is not on the soul of poetry! But the goal of growing in hits.”

This trove of poems might have been forever lost had Jason Scott not arrived on the scene. Scott is the top-hat-wearing impresario of the Archive Team, a loosely organized band of digital raiders who leap aboard failing websites just as they are about to go under and salvage whatever they can. After word of what was about to happen at Poetry.com reached the Archive Team, 25 volunteer members of the group logged in to Internet Relay Chat to plan a rescue. “We were like, well, screw that!” Scott recalls. When sites host users’ content only to later abruptly close shop, he says, “it’s like going into the library business and deciding, ‘This is not working for us anymore,’ and burning down the library.”

Scott and the Archive Team do not seek permission before undertaking one of their raids, though as a rule they only go after files that are publicly available, and Scott says most sites do not complain. They devised code that would copy the poems on Poetry.com and duplicate them in a network of donated server space in such far-flung places as London, Egypt, and Scott’s own home in New York state. The members working to save the contents of Poetry.com, who are known by such handles as Teaspoon, DoubleJ, and Coderjoe, met up on one of the Archive Team’s IRC channels and divided the poems into blocks, ranging in size from 100,000 to one million files. Most of the team began on the poems that might be considered the best—the ones with the most votes and awards—and worked backward from there.

Unlike other operations, this one encountered resistance. “Poetry.com was actively working against us at every turn,” says Alex Buie, a high-school senior from Woodbridge, Virginia, who collaborates with Scott on the Archive Team. Buie says someone from Poetry.com e-mailed to complain that the Archive Team was scaring away the company that was about to buy the site. The site even blocked some of the Archive Team members’ IP addresses, he adds. But the group persisted. By the time Poetry.com went dark, the team had saved roughly 20 percent of its poems. Today the site is a wasteland, filled with eerie, spam-filled forums and promises by the new owner to restore users’ poetry at some point in the future.

CHEATING DEATH

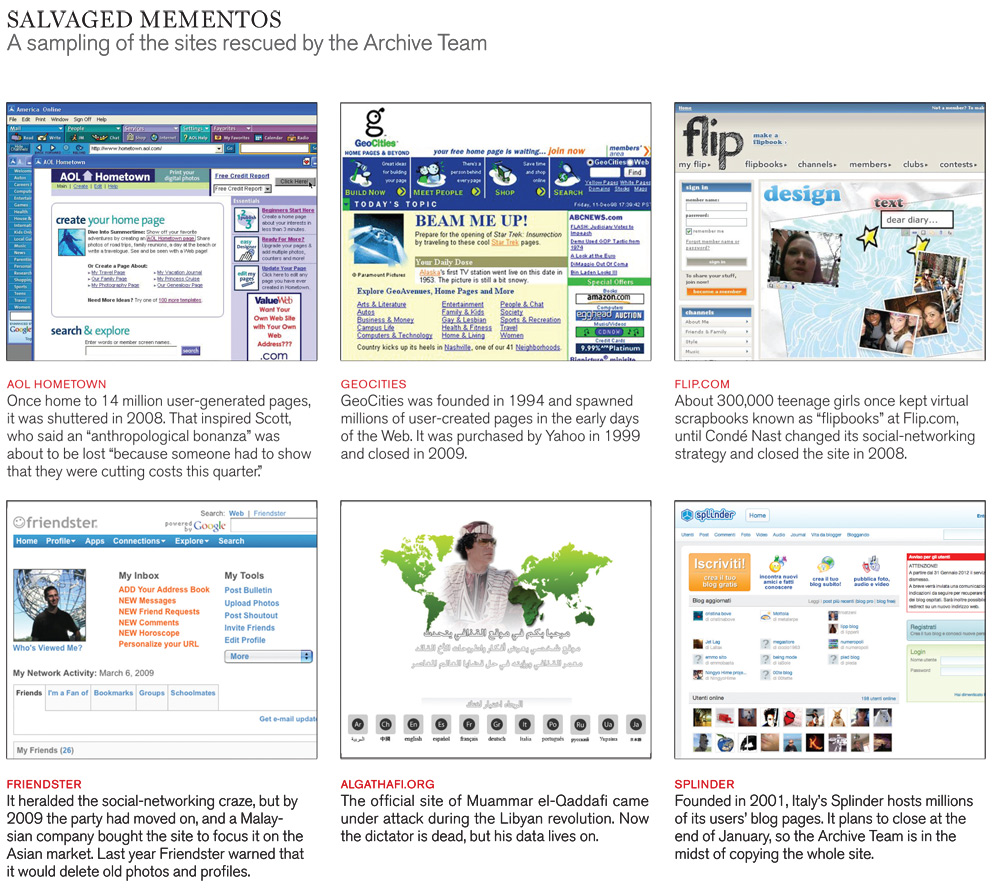

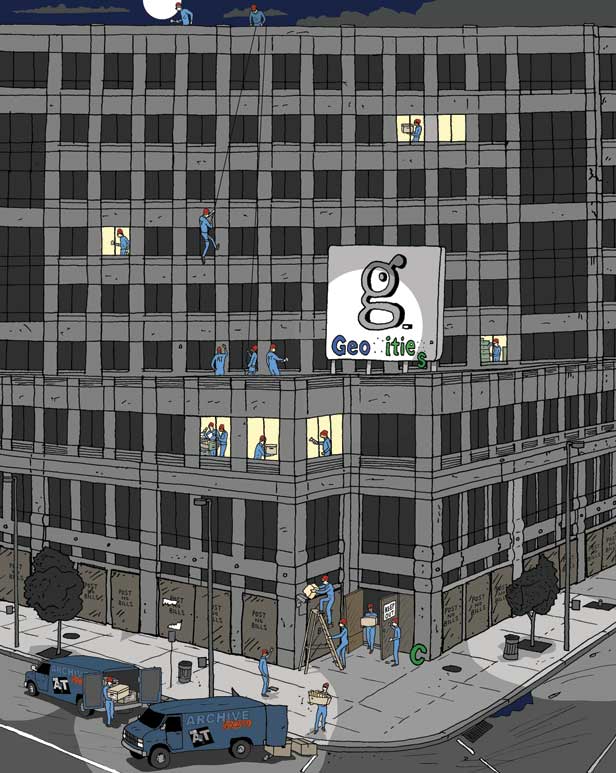

People tend to believe that Web operators will keep their data safe in perpetuity. They entrust much more than poetry to unseen servers maintained by system administrators they’ve never met. Terabytes of confidential business documents, e-mail correspondence, and irreplaceable photos are uploaded as well, even though vast troves of user data have been lost to changes of ownership, abrupt shutdowns, attacks by hackers, and other discontinuities of service. Users of GeoCities, once the third-most-trafficked site on the Web, lost 38 million homemade pages when its owner, Yahoo, shuttered the site in 2009 rather than continue to bear the cost of hosting it. Among the dozens of other corpses catalogued by the Archive Team’s “Deathwatch” are AOL Hometown, Flip.com (a scrapbook site for teenage girls that once had 300,000 members), and Friendster, of which the Archive Team managed to salvage 20 percent. “How many more times will we allow this?” an outraged Scott wrote on his blog after the AOL Hometown shutdown. He compared the lost user home pages to “a turkey drawn with a child’s hand or a collection of snow globes collected from a life well-lived.”

The personal quality of such data piques Scott: in his eyes, each page that the Archive Team salvages bears the singular mark of the person who made it. Rescued files from Petsburgh, the GeoCities subdomain devoted to pets, include a memorial to Woodro, a Shar-Pei who lost his battle with lung cancer on January 5, 1998. Woodro apparently loved Jimmy Buffett, so his owners paid tribute to his life with the song “Lovely Cruise.” It is minutiae like these—evidence of everyday people expressing themselves in a particular place and time—that the Archive Team rescues by the thousands.

Scott’s interest in technology, which began with a childhood love of electronics and early personal computers, bloomed in the 1980s and early ’90s with the birth of digital bulletin board systems. In 1990 he and a friend created TinyTIM, a multiplayer virtual adventure that’s now the longest-running game of its kind. Ten years later, Scott founded Textfiles.com, dedicated to preserving mid-1980s text files “and the world as it was then,” bulletin board systems and all. In 2009, he founded the Archive Team, and last March he became an official employee of the Internet Archive, the San Francisco–based nonprofit behind the Wayback Machine, Open Library, and other projects to preserve online media. The Archive Team acts independently and has no formal affiliation with the Internet Archive, but data rescued by the Archive Team often ends up stored on the Internet Archive’s servers. “I didn’t want to bureaucratize the guy,” says the Internet Archive’s founder, Brewster Kahle, who hired Scott. “The question for us is how to have a relationship with a volunteer organization in a way that’s not stifling from their perspective or frightening from ours.” Scott’s dual role allows the Internet Archive to take selective advantage of the Archive Team’s more aggressive data-gathering techniques while maintaining an arm’s-length relationship. Many differences between the two groups can be summed up by the icons that appear beside their URLs in Web browsers—for the Internet Archive, a classical temple, and for the Archive Team, an animated hand flipping visitors the bird.

During my reporting for this article, Scott refused to speak with me for reasons that he declined to explain, but when contacted by a second reporter who also said she was working for Technology Review, he discussed his life and work at length in e-mails and phone calls. Born Jason Scott Sadofsky, he is 41 years old and divorced. He lives with his brother’s family about 70 miles north of New York City in Hopewell Junction, near the Hudson River. In the backyard is a storage container he calls the “Information Cube,” which holds his vast collection of obsolete electronic equipment, computer magazines, and floppy discs, all part of his broader calling as an independent historian of the computer. In 2005, Scott created a five-hour documentary on early bulletin board services, and in 2009 he raised $26,000 in donations to support his rescues of digital history. His second documentary film, Get Lamp, about text-based computer games from the 1980s, debuted in 2010. Scott also evangelizes for data preservation on the tech-conference circuit, where his affinity for the old is sometimes reflected in his wardrobe. For example, he has been known to deliver a presentation in steampunk regalia—aviator-style goggles, a velvet jacket, and the top hat. Day to day, the widest outlet for his showmanship is the 1.5-million-follower @sockington Twitter feed written in the voice of his cat, Sockington, who makes such faux-naïf kitty quips as “#occupylitterbox” and “crunked on nip.” “He is like a 19-year-old guy in a 40-year-old body,” says Buie.

With his enthusiasm for archaic technologies, Scott is a throwback to the Internet’s early days, when impassioned amateurs would banter on the WELL or hash out the new medium’s technical specifications in request-for-comment papers, along with computer scientists from government and academia. The online community was smaller then, and more countercultural. Too primitive to attract major outside investment, the medium spent the 1980s guided by people like Jason Scott. Part of the appeal of volunteer projects like the Archive Team is that they offer a sort of time machine back to an online world that was less about money and more about fun.

DOODLES AND MEMORIES

Typically, Archive Team members extract data from failing sites using a crawling program like GNU Wget, which lets them quickly copy every publicly available file. The files are then sent to the Internet Archive for storage, or uploaded to one of the loose network of Archive Team servers scattered around the world. The hardest part, Scott explains, is knowing when a site is going down without warning. That happened to Muammar el-Qaddafi’s website during the Libyan revolution that ended in his death. “It’s an art, not a technical skill,” Scott says. An Archive Team user who works under the handle “Alard” was able to copy Qaddafi’s site, including videos and audio files of the late dictator. Now these materials are freely available to anyone.

Another recent rescue: Italy’s Splinder.com, which is host to half a million blogs and announced its impending closure in a November blog post. Scott heard about Splinder through the Archive Team’s grapevine of volunteer archivists, who will often send him e-mail and Twitter messages or add a page directly to the Archive Team’s wiki. “People put out a bat signal,” Scott says. By November 24, word of Splinder’s troubles had reached Scott. More than a dozen members of the Archive Team “went in with guns blazing,” he says, racing to copy as many of its 55 million pages as they could, causing the site to crash twice. Ultimately, Splinder’s owners acquiesced to angry users and pushed the shutdown date back to January 31.

The next phase of a typical Archive Team mission is less exciting than ripping as much information as possible from a website before it disappears, but just as necessary for the salvaged data to be of any use. Archivists check the integrity of the downloaded data and then distribute it for storage. Larger collections may be released as torrents, which anyone can download over the peer-to-peer service BitTorrent, on sites like thepiratebay.org. The GeoCities archive was so big that at first Scott put out a call asking anyone with an available terabyte-sized hard drive to mail it to his home, where he would load the files and arrange for return postage. More than a dozen people from Scott’s network volunteered to help safeguard the GeoCities cache until it was ready to be released as a torrent.

The Archive Team requires “a certain kind of person who’s sort of reckless while still being methodical,” says Duncan B. Smith, who works with the group under the handle “chronomex.” “People live for the big efforts where people mobilize and download the fuck out of some website run by assholes. After the fire’s out, though, you still have to stick around to clean the fire truck and put the gear away. You have to upload your data to the centralized dump to be collated. Then you have to talk over why your data seems slightly broken. That’s the boring part.”

Is it legal to copy stuff from websites without permission? U.S. courts haven’t made a clear determination. Andy Sellars, a staff attorney at the Citizen Media Law Project, says he would argue that it counts as “fair use” under copyright law. However, he notes that the Archive Team’s torrents don’t offer a mechanism for copyright holders to demand that certain material be taken down, which could hurt its case in a court. “If you look at the letter of copyright law, it’s pushing the envelope,” says Jonathan Zittrain, codirector of Harvard’s Berkman Center for Internet and Society. But because the Internet Archive has been engaged in similar work for years, Zittrain says, “now the radical move would be for the courts to forbid it. Soon it will be another part of the furniture.”

THE DATA HOARD

GeoCities is probably the best example supporting Scott’s argument that apparently silly or worthless data can have unanticipated cultural value. Today the 652-gigabyte torrent that the Archive Team made available in October 2010 is free to anyone who wants to have a look. The most impressive project this release has spawned is the DeletedCity, a ghostly video interface that allows users to explore various GeoCities subdivisions and content. On the micro level, the Archive Team has been able to dig up and return the content of individual GeoCities users, like a late World War II veteran who had put his photo archive on the site. After GeoCities went down, the Archive Team uploaded the old pictures to a USB drive and mailed it his widow, free of charge. Phil Forget, a 26-year-old programmer in New York, used the GeoCities torrent to dig up his old images from the Japanese anime series Dragonball Z as well as animated caricatures he had made of his high-school teachers. The material isn’t as significant to him as the widow’s photographs were to her, but it is far from trivial. “It’s like if you went back to your mom’s house and found the doodles on the back of your marbled notebook, from fourth or fifth grade,” Forget says. “You get this rush of memories.”

Listening to Scott talk about the importance of our collective “digital heritage” makes the loss of sites like GeoCities feel as tragic as the burning of the Library of Alexandria, a vast archive of ancient texts, many of which existed nowhere else. (The library has a joking listing on the Archive Team’s site, which lists its URL as “none” and the project’s status as “destroyed.”) Scott scoffs at the suggestion that material like the verses on Poetry.com might not be worth saving; he notes that the New York Public Library stores old menus in its rare-books collection. “No one questions that,” he says.

Scott’s two holy grails are the archives of Compuserve, which was one of the major online services of the dial-up era before eventually being absorbed by AOL, and those of a past incarnation of MP3.com, which formerly was devoted exclusively to independent musicians who wanted to share their work. “I bristle when I see that level of culture wiped away,” he says. Scott believes that the archives of both sites must be out there somewhere; perhaps they are on reels of magnetic tape gathering dust in a garage. Sometimes he can appear to have an almost Peter Pan-ish unwillingness to accept the passage of time and the way information gives way to entropy. To him, the idea of data that cannot be saved is almost as heretical as the notion of data that is not worth saving.

Scott approaches today’s multibillion-dollar repositories of user data—sites like Facebook, Google, and Flickr—with intense skepticism. The sister page of the Archive Team’s Deathwatch is called “Alive … OR ARE THEY?” and makes it abundantly clear that the data ethics of Mark Zuckerberg and Larry Page are being carefully watched. Facebook “seems stable at the moment,” says the Archive Team, while Google “wants you to think they will be here forever.” Some posters on the Archive Team wiki have already criticized Google for closing down Google Labs, a section of the site devoted to experimental projects, and for warning that it might stop hosting previously uploaded content at Google Video. “Don’t trust the Cloud to safekeep this stuff,” Scott has warned.

“I get very cranky,” he says. “You know the Google ad where the parent is recording family memories on YouTube, and keeping photos on Picasa, and telling his kid, ‘I can’t wait to share these with you someday’? Well, not if you keep it on Google. They make these claims that you can keep things forever, but in fact it’s all temporary.”

Buie, the high-school senior, argues that keeping old data serves a purpose whether or not anyone is using it now. “Take the Friendster stuff,” he says. “Maybe no one will look at it until 2250. That doesn’t matter to me. What matters is that the knowledge is there.” Buie found the Archive Team through his avocation as a historian of early hardware. He had gone to a “too good to waste” section of his county’s dump, looking for early computers to refurbish and add to his collection. After bringing home an Apple II and scouring the Web for information on spare parts, he saw a reference to a defunct GeoCities page that had the information he was looking for, and his search for this page led him to the Archive Team’s GeoCities project. Now Buie frames his work with Scott as part of the solution to a broader cultural problem on the Web. “There isn’t enough focus on the past, on where we came from,” he says. “And if you forget the past, then the future becomes meaningless, because you don’t even know how you got to where you’re standing.”

As Scott continues to project his message with maximum bombast, it appears that some of the Web’s leading brands are coming around to his views. When Google launched its social-networking service Google+ last June, it introduced a new feature called Takeout that would combine users’ posts and export the files for them. Gmail already let users export their contact lists, making it easier to switch to competitors’ products. “I personally won’t be happy until every last bit of your data is available through Takeout,” says Brian Fitzpatrick, an engineering manager at Google who leads the company’s data liberation efforts. He says Google should do it so that users trust the company: “It’s not because we’re nice.” Though Facebook declined to comment for this article, it has added a Takeout-like “Download a Copy” function for the photos, messages, and other content users keep on the site.

As for Scott, he is looking further ahead. He’s already planning for that distant day when his most important piece of metadata—the knowledge he has amassed of his own collections—will go blank. “Mortality?” he says. “I have a distributed array of servers. Whatever I acquire, I share out as fast as possible. None of it is sitting on a hard drive in one guy’s house.”

Matt Schwartz is a freelance writer whose work has appeared in Wired, the New Yorker, and the New York Times Magazine. He reviewed Foursquare and Scvngr in the March/April 2011 issue of Technology Review.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.