The Evolution of Cambridge

Mike Bonislawski is a Cambridge lad. He grew up in a two-story house on Portsmouth Street, went to school down the road, and got his first job at 15, working five minutes’ walk from his house in a factory that made plastic heels for ladies’ shoes. Bonislawski began his career like many of his neighbors—as a factory hand in East Cambridge, sawing, painting, shaping, welding, and operating machinery in factories that made rubber hoses, aprons, and Ping-Pong paddles. He went on to become a college professor with a PhD. Now 61, the lifelong Cambridge resident has seen his neighborhood morph from an industrial zone to a mecca of high tech, biotech, and academia.

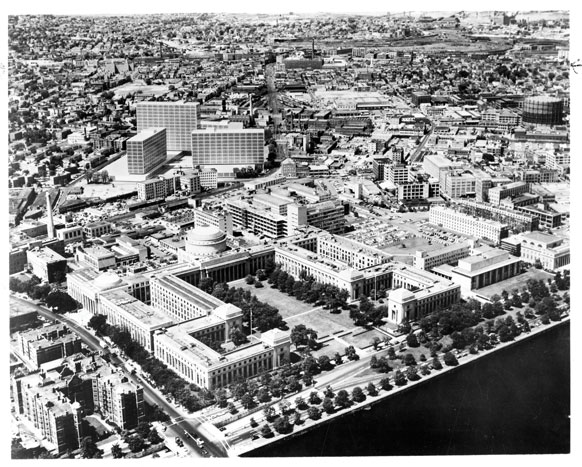

The Cambridge of Bonislawski’s youth can be seen quite clearly in an aerial photograph that a U.S. Navy blimp took in 1945. Open parking lots, flat factory roofs, and brick-walled warehouses dominate the landscape, and dirt roads skirt industrial grounds. Smokestacks rise like dandelions from the factories and industrial complexes that surround Killian Court, belching alongside MIT’s campus.

In those days, MIT students were reminded of the Institute’s industrial neighbors every time they took a lungful of city air. “There were fat-rendering plants,” says Martin Klein ‘62. “You could see open trucks go by with mountains of animal bones.” He remembers the smell as “nauseating.” Then there was rubber: David Chapman ‘67 recalls walking out of the East Campus dorm into the prevailing north winds on cold winter days and being overwhelmed by “the smell of burning rubber from a tire reclamation plant.” Most pleasant was the scent of chocolate that wafted from the city’s 29 confectionery manufacturers.

Today Cambridge is a different place—and the Institute has played a key role in its transformation. Since MIT moved across the river in 1916, having purchased almost 50 barren acres filled in with mud from the Charles River and dirt from subway excavations, its campus has grown and spilled over into space once occupied by factories. Its alumni have started businesses in the shadow of the Great Dome. And the Institute has worked with the city to help transform abandoned factories and aging tenements into office and lab space for companies drawn to the brainpower that MIT helps supply. These days, Google and Microsoft have offices in Kendall Square, and biotech and pharmaceutical companies such as Amgen, Biogen Idec, and Novartis maintain large operations in the area. In all, it houses more than 150 biotech, IT, clean-energy, and other technology companies. And MIT is now in the planning stages of a project to revitalize MIT-owned parcels near the Kendall MBTA station. The idea is to bring the energy of the neighborhood’s labs and office buildings to the street level, giving workers, Cambridge residents, and members of the MIT community places to connect, collaborate, and socialize.

Cambridge’s Industrial Heyday

In the early 1800s, Cambridge was billed as a shipping port. Developers invested heavily in roadways to funnel traffic across their new bridges between Cambridge and Boston: the West Boston Bridge Company had just constructed one where the Longfellow stands now, and Andrew Craigie had built the Canal Bridge near the current Museum of Science. But the War of 1812 brought a blockade to the Eastern Seaboard, thwarting plans for Cambridge’s ascension as a commercial center. The city was left with a grid of roads and open space in between. “It was laid out in plots and cut up, and had streets laid out, but didn’t have a huge residential population,” says Gavin Kleespies, executive director of the Cambridge Historical Society. “This made it really a fantastic area for an industry to move into, because it was a blank slate without a whole lot of people living in it who would get into their way, and [it had] a huge infrastructure laid out for them.” By the beginning of the Civil War, Cambridge was thriving as an industrial town.

Skilled crafts moved in first. Through the mid-1800s, manufacturers built carriages, fine furniture, pianos, and telescope lenses. In the mid to late 1800s, immigrants from Ireland, Italy, Portugal, and Eastern Europe settled in pockets of East Cambridge and provided a ready pool of labor. Positioned at the confluence of rail and shipping routes, Cambridge now attracted bigger businesses, which soon built factories small and large.

During this industrial heyday, the slice of Cambridge between the river and Landsdowne Street, which runs parallel to the railroad tracks, hosted the main complex of the New England Confectionery Company (Necco), the Whiting Milk Company, the Ward Baking Company, the National Biscuit Company (which would later become Nabisco), and more, including a Heinz warehouse that once stored ketchup and mustard. The H. P. Hood & Sons dairy and the shoe polish maker Whittemore Brothers occupied the corner of Albany and Mass. Ave. until the mid-1940s.

Bonislawski recalls visiting a rubber factory where his friend’s father worked. “I remember going in and seeing all the machines and hearing all the noises,” he says. “There were a couple of places that actually extruded Styrofoam into various shapes. If you wanted to make a mattress or a seat cushion out of rubber, there were machines that did that in factories.”

Farther east, on the corner of Ames and Main Streets, the Daggett Chocolate Company made its confections from scratch for seven decades, processing imported cocoa beans in an adjoining facility that would become the site of the Media Lab’s first building. “Here, the cocoa beans would be rendered into cocoa liquor and pumped into the building next door to be manufactured into chocolates,” says O. Robert Simha, MCP ‘57, MIT’s director of planning for 40 years and author of the book MIT Campus Planning 1960-2000. Carmela LaConte, now 92, worked at the Daggett factory for eight years, along with her father, aunts, and cousins. “I was a feeder,” she says. “I was in a line with three other girls, and we used to put the candy on a belt.” LaConte remembers that the factory was spotless. “We had to have white uniforms on,” she says. “We had to keep our hair in—everything had to be clean.”

And across Ames Street, the United-Carr Fastener Corporation’s machines clanged away, producing metal parts—hooks, bolts, nuts—for the clothing and automobile industries until the early 1980s. “That company operated 24 hours a day, stamping out little gadgets to hook things together,” says Simha.

But the Lever Brothers soap factory, which sprawled across 30 buildings in a plot at Portland and Broadway, dwarfed them all. “Lever Brothers was enormous,” says Bonislawski, who lived near the factory grounds. “They had a little park there—in the middle of it was an ornamental fountain. I remember going there as a kid to run through the water. It was gigantic, block after block, and they had these big water towers. It was tall, too—it was an impressive site.” Near the height of Cambridge’s manufacturing boom, the Lever Brothers plant employed 1,300 workers; in 1925, the Cambridge plant and one in Philadelphia churned out close to 40,000 tons of soap between them.

The End of an Era

Around the mid-1940s, the character of the city began to change. Hood was one of the first businesses to go. In 1946, the U.S. government bought its factory building on behalf of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission. MIT scientists from the Department of Metallurgy began using the facility where ice cream had once been made to study beryllium and zirconium, which were used in the construction of nuclear reactors. An independent company, Nuclear Metals, took over the work in 1952 but moved to new space in Concord in 1958. No longer of use to the government, the building became the property of MIT, which vacuumed out its ventilation ducts, used soap and water to flush toxic dust particles from the walls and floors, and then tore it down.

By the mid-1950s, factories were closing all across Cambridge. Labor costs were lower in the South and the Midwest, and factories that had been in the city for decades failed to invest in new machinery. Over the next 30 years, sometimes slowly, sometimes suddenly, scores of factories closed down. Some of the old mill buildings were rented by MIT startups looking for cheap space; others remained vacant.

In 1959, Cambridge suffered a serious blow when Lever Brothers decided to shift its headquarters to New York and its production to other parts of the country. Instead of reinvesting in its plant at Portland Street and Broadway, which had been operational since 1898, the company moved out of Cambridge and put the land on the market.

With Lever’s departure, the city lost a vital source of revenue, and Mayor Edward Crane was keen to attract taxpaying businesses to the vacant plot. So he approached the MIT Corporation with the idea of converting the factory complex and an adjoining site formerly occupied by a housing tenement, which together covered almost 15 acres, into a research park. The proposal struck a chord with James Killian, then chairman of the Corporation.

Soon, with the city of Cambridge’s coöperation, MIT went into partnership with the private development company Cabot, Cabot & Forbes, acquired the property, and established Technology Square, with the goal of “making a clean sweep of the area and starting afresh,” says Simha. This, he says, marks the start of “the transition from gradual change—one building at a time, one company at a time—to a more organized and more aggressive process of change.”

Tech Square suited Killian’s interest in having MIT interact more directly with its immediate neighborhood. In time, he hoped to entice commercial pioneers in science and technology to set up shop in Cambridge and make the city more attractive to people involved with academic research. “We believe that enlarging the professional scientific and engineering community here would strengthen the universities and the industries in this area,” he said at a luncheon meeting with the Cambridge Redevelopment Authority in January 1960, when he announced MIT’s intention to invest in Tech Square.

Cabot, Cabot & Forbes finished the first of Tech Square’s five buildings in 1963; the second opened in 1964. Renting was slow at first, but Polaroid eventually moved in, and General Electric rented space alongside MIT’s Laboratory for Artificial Intelligence. Firms committed to research and innovation soon filled Tech Square. In addition, Simha writes in his book, “Technology Square’s success inspired the NASA Electronics Research Center to set up its headquarters in the adjacent Kendall Square in 1967.”

The New Cambridge

Tech Square set in motion Cambridge’s transition from an industrial town to a research center that taps into the intellectual resources offered by MIT and Harvard. In the new Cambridge, red brick has given way to concrete and sheet glass, and rubber factories, meatpacking companies, and chocolate factories have been supplanted by offices and lab space. And as industry left Cambridge, space also became available for MIT to expand.

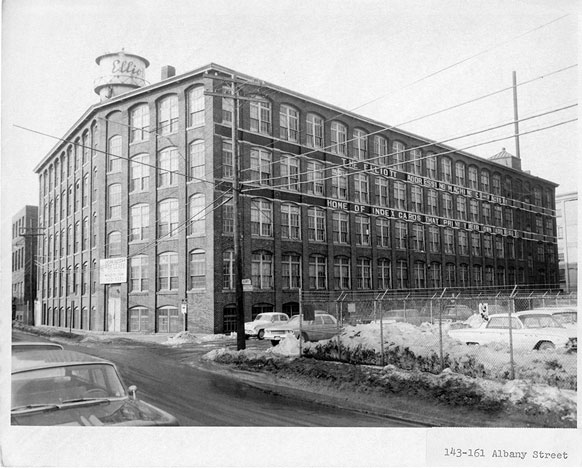

In 1961, the Daggett business merged with Necco, and MIT bought its building. Now known as E19, it houses laboratories, the Knight Journalism Fellowship program, and the Institute’s human-resources department. The Koch biology building and the new David Koch Cancer Institute stand on the former site of the United-Carr Fastener Corporation. And when the Elliott Company, which made address-label machines, relocated in 1964, MIT bought its Albany Street building and leased it to a colorful string of occupants—the Paramount Coat Company, the Revelation Bra Company, and a series of small publishers—before gutting the structure and renovating the inside. It opened as the graduate dorm Edgerton House in 2001.

Today, Albany Street has become a vibrant part of MIT’s expanding campus. The railroad running alongside it is still active, and several original building façades remain intact. But the street now houses labs working on plasma physics and magnetic resonance, the pale-blue tank containing MIT’s nuclear reactor, and three large graduate-student dorms.

Bonislawski saw the changes coming. After working as a laborer and then a skilled machine operator for 20 years, he watched factories closing down and workers being laid off. “You don’t have a choice—you have to convert,” he says. “I could see that manufacturing was leaving the Boston area.” So, like the city itself, Bonislawski “converted.” In his mid-40s, he enrolled at the University of Massachusetts in Boston while still working full time, earning a bachelor’s degree in 1989 and a master’s degree in 1992. He went on to get a PhD in labor history from Boston College in 2002 and taught history, first at Salem State College and then at Cambridge College, where he now teaches part time.

Even though he adapted, Bonislawski still misses the factory days. The old Cambridge “had this sense of community,” he says. “For instance, Boston Woven Hose also sponsored the local Boy Scout troop. So your father might work at the plant but then be involved with the Boy Scouts in the evening. Now there are just these sterile buildings and I don’t know what they do there.”

That is just the kind of thing MIT hopes to address as it works with Cambridge officials to begin enhancing Kendall Square at the street level. In September, a series of brainstorming sessions open to students, faculty, staff, and community members explored ideas for enlivening the neighborhood’s publicly accessible spaces. Ideas tossed around include creating new spaces for specialty grocers, diners, book fairs, outdoor music and dancing, and public art and interactive exhibits celebrating technology. The final proposal, which will probably require significant changes in zoning, is expected to result in a mixed-use redevelopment of MIT’s Kendall Square properties that will most likely include ground-floor retail and restaurants, public gathering spaces, housing, and corporate, academic, and research space.

“Kendall Square is home to a kind of creative intensity that you don’t encounter many other places on earth: it has an entrepreneurial culture and an incredibly inspiring focus on society’s important problems,” MIT president Susan Hockfield said in an address to the Kendall Square Association last February. “If we want Kendall Square to grow and thrive over the long term, we need to make sure that the most creative entrepreneurs and most talented inventors and scientists find Kendall Square so magnetic, so appealing, that they can’t think seriously about other options.”

Even as Cambridge continues to evolve, a corner of it pays homage to its industrial past. At the northwestern edge of MIT’s campus, in part of the vast plot once occupied by the Simplex Wire and Cable Company, University Park is a little green oasis among upscale apartment blocks, laboratory buildings, and cafés. Its lawns are sprinkled with a number of peculiar metal ornaments, including a scale model of three telescopes pointing toward the sky, a six-foot-high cabling spool, an architect’s model of the Simplex factory complex, and a brass replica of a spilled paper bag of Necco’s famous Conversation Hearts. Located just west of Mass. Ave. on Sidney Street, not far from the old Necco factory (now Novartis) and the old General Radio Company building (now the MIT Museum), it serves as a small testament to Cambridge’s occupants of yesteryear.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.