New Chip Captures Specialized Immune Cells

A novel microfluidics chip developed by researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) will let doctors examine how white blood cells called neutrophils help the body cope with burns and other traumatic injuries. It may also shed light on why the immune system sometimes spirals out of control, resulting in dangerous inflammation.

The chip lets scientists do something they’ve never before been able to do: quickly and easily capture neutrophils from a small volume of blood. In the long term, scientists hope to use this technology to predict which patients are most likely to develop serious infections after an injury and therefore need the most aggressive treatment. “People have been looking for biomarkers for injury and sepsis [blood poisoning] for a long time,” says Steven Calvano, a researcher at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School. Calvano, who was not directly involved in the project, says, “This could be an extremely valuable clinical tool.”

Damage to the skin’s protective barrier, like the kind that occurs with traumatic injuries and severe burns, makes patients dangerously susceptible to infection. Neutrophils, the most abundant white blood cell in the body, are one of the immune system’s first responders. They rush to the site of damage, where they devour bacteria and other invaders.

Recent research suggests that these cells also play a subtle role in the immune system, helping to regulate the immune response. An overreaction of the immune system after injury can cause systemic inflammation, which can be just as dangerous as the initial infection or damage. So if researchers can get a better picture of how these cells behave, that could lead to new drug targets to prevent or treat sepsis and inflammation. “Regulation of these cells is really the key to be able to target and change the overall response,” says Carol Miller-Graziano, director of the Immunobiology and Stress Response Laboratories at the University of Rochester Medical Center. Miller-Graziano took part in the MGH project.

Until now, isolating these cells from blood has been lengthy and technically challenging. But a novel microfluidics chip developed by Ken Kotz and collaborators at the Center for Engineering in Medicine at MGH is changing that. In a study published online last week in the journal Nature Medicine, researchers showed that the device could capture the cells as effectively as traditional methods but in much less time. They also showed that a small volume of blood–150 microliters–generates enough cells for later analysis. The research is part of a large multicenter grant, funded by the National Institutes of Health, to better understand inflammation and how the body responds to injury.

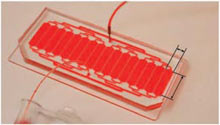

About the size of a business card, the device uses technology that the team initially developed to monitor T cell counts in HIV patients. An organic polymer sandwiched between two glass slides is carved with 16 channels, which are coated with an antibody that binds specifically to neutrophils. The antibodies selectively capture the cells as blood flows through the device. The capture process takes only about five minutes, and is simple enough to be done by a nurse or doctor at the patient’s bedside. “We engineered it to be as simple as possible,” says Kotz. Scientists then add different chemicals to the chip to isolate DNA, proteins, or other molecules from the cells. These molecules are then sent for further analysis.

A quick capture procedure is especially important for neutrophils. Researchers want to study the genes and proteins that become active in the cells after injury, and a lengthy or arduous isolation process can artificially activate some molecules, or kill the cells altogether. Kotz says that the new technology was much more effective than traditional methods at generating adequate amounts of RNA for later analysis.

Kotz and his team are developing similar chips to capture other types of immune cells. They have already isolated and analyzed lymphocytes, which include the immune cells that make antibodies against bacteria, and are now working on monocytes, another type of immune cell. The ability to separate and study the different immune cells individually will give researchers a better idea of the role each cell plays in the immune response, and how different cells might be targeted if something goes wrong.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.