From the Labs: Biomedicine

Growing New Livers

Scaffold from damaged organs may provide the basis for new ones.

Source: “Organ reengineering through development of a transplantable recellularized liver graft using decellularized liver matrix”

Basak Uygun et al.

Nature Medicine 16: 814-820

Results: Researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital, in Boston, grew new livers by removing the cells from an existing rat liver and seeding the scaffold left behind with healthy liver cells. The new organs were able to function for a short time when transplanted into rats.

Why it matters: Not enough donor livers are available for everyone who needs one, and the organ’s complex three-dimensional structure has made generating replacements very difficult. The research could one day provide a way to use unhealthy organs to grow healthy ones.

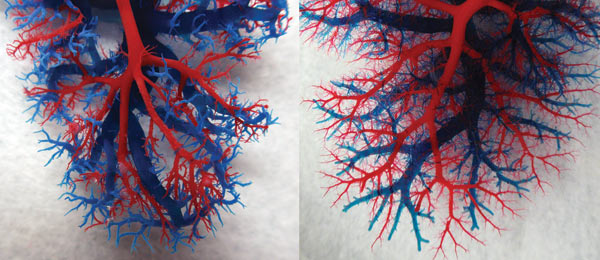

Methods: Scientists used a detergent to remove cells from the existing liver, leaving a scaffold of proteins and other molecules. The basic architecture of the liver’s complex network of blood vessels remained intact. To the empty scaffold, the researchers added a mixture of liver cells and endothelial cells, the cells that line blood vessels. The cells grew into an almost complete organ that functioned for 10 days in a dish and for up to eight hours in live animals.

Next steps: The researchers plan to transplant the organs into rats for longer periods to see if they might function well enough to replace a damaged liver. This will require adding more endothelial cells, because the current reconstructed livers don’t have enough blood vessels to work properly for long. The team is also experimenting with using stem cells rather than liver cells to populate the scaffold, which could potentially enable patients to use their own cells.

Cheap Blood Typing

A 10-cent paper test could improve medical care in poor countries

Source: “Paper diagnostic for instantaneous blood typing”

Gil Garnier et al.

Analytical Chemistry 82(10): 4158-4164

Results: Researchers made a blood-typing test from a piece of paper treated with antibodies. It can determine an individual’s blood type as accurately as more complex existing methods.

Why it matters: Blood transfusions can cause a potentially fatal reaction if the recipient’s and donor’s blood types conflict. Current methods of determining blood type require costly machinery, which is often difficult to obtain or maintain in poor countries. The new test costs about 10 cents to make.

Methods: Using an ink-jet printer, researchers printed a pattern of channels on paper with hydrophobic ink. Then they used the printer to deposit antibodies designed to bind to specific molecules associated with the different blood types. On each of three tabs extending from the center of a piece of paper, they printed a different antibody within the channels. Blood dropped into the center diffuses along the tabs and stops when it encounters the antibody that matches the molecule characteristic of its type. Scientists read the results by assessing how far the blood has traveled down the tabs.

Next steps: The researchers are now looking for industrial partners to bring the diagnostic to market.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.