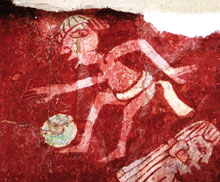

Ball games were a serious matter to the ancient peoples of Mesoamerica, the region encompassing Mexico and parts of Central America that was the territory of civilizations including the Olmecs, Aztecs, and Maya. The ceremonial games, played on stone-walled courts using large balls made of solid rubber, were an important part of the cultures’ religious rituals.

These ancient people also used rubber to make sandals, figurines, and a variety of other objects, and it appears that they were incredibly adept at processing this versatile material. Research by professor Dorothy Hosler and technical instructor Michael Tarkanian of the Department of Materials Science and Engineering, reported this year in Latin American Antiquity, provides new evidence that the Mesoamericans had perfected a system of chemical processing to fine-tune the properties of the rubber depending on its intended use.

For the soles of their sandals, they made a strong, wear-resistant version. For rubber balls, they processed the material for maximum bounciness. And for rubber bands and adhesives used in making ornaments and weapons, they optimized its resilience and strength. In other words, they were the Americas’ first polymer scientists, Hosler and Tarkanian say.

Mesoamericans processed the sap of rubber trees (latex) by mixing it with juice from morning glory vines, apparently using different quantities of the two ingredients to change the properties of the resulting rubber. Until the new research, nobody had shown that it was possible to achieve these different properties simply by varying the recipe’s proportions. The new work draws on a combination of laboratory experiments, analysis of recovered artifacts, and the descriptions left by early European explorers, who had never seen rubber and struggled to find words to describe it.

The ancient rubber that has survived tends to be so degraded that it can’t be tested for its mechanical properties. So Tarkanian and Hosler made batches of rubber with varying proportions of the two plant ingredients, which they collected on field trips to Mexico. When they tested the finished products to measure wear resistance, elasticity, toughness, and other properties, they found that a 50-50 blend of latex and morning glory produced maximum elasticity. Pure latex worked best for making adhesive rubber. And a three-to-one mix of latex and morning glory provided the most durable material.

The Mesoamericans had plenty of time to work out how best to achieve these different properties through trial and error. Rubber balls from the region have been dated to as far back as 1,600 years bce.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.