Russian Spies’ Use of Steganography Is Just the Beginning

One of the ways the 10 Russian spies that the U.S. just sent home to the motherland in a spy swap communicated with their handlers was via steganography - the act of embedding secret information in some other signal.

In this case, the spies were embedding messages in images that were then uploaded to public websites. The messages weren’t encrypted - just invisible to the naked eye; lost in the endless stream of communications transmitted daily through the web.

Here’s the thing about steganography: it doesn’t take much to implement it in almost any signal you can imagine - and doing so is surprisingly trivial. There are over 600 different known steganography programs, according to digital forensics firm WetStone Technologies, and the one the Russian spies used was custom-made.

Indeed, it’s so easy to write a steganography program that Jon McLoone, head of international business and strategic development at Wolfram, wrote one in Mathematica with just a handful of lines of code. He helpfully points out that his version, unlike the one the spies were using, isn’t likely to crash.

But this is just the beginning: the principles of steganography can be applied even to continuous communications, such as conventional wireless networks. Using this approach, Krzysztof Szczypiorski and Wojciech Mazurczyk figured out how to pour up to a megabyte per second into an open wireless network.

Steganography can also be implemented in sound files and VoIP protocols. Here’s a scenario from Stegano.net, the leading site on steganography: “An employee of an electronic equipment factory uploads a music file to an online file-sharing site. Hidden in the MP3 file (Michael Jackson’s album Thriller) are schematics of a new mobile phone that will carry the brand of a large American company. Once the employee’s Taiwanese collaborators download the file, they start manufacturing counterfeit mobile phones essentially identical to the original–even before the American company can get its version into stores.”

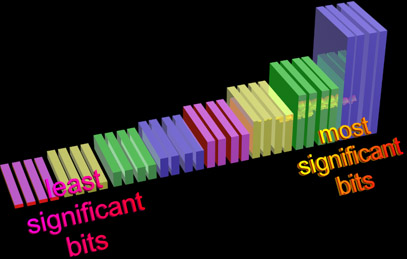

Steganography works because it’s possible to hide secret data in all the wasted or less-essential bits in any communication. All files have what are known as least significant bits - they’re the part of any binary number that, when lost, does the least to change the value of the value it represents. (By analogy, the least significant digit of decimal integer 43.218 is 8, and if you lose it you’ve hardly changed the value of that number for most purposes.)

These bits are especially disposable when you’re dealing with files that only have to be perceived by a human - throwing out or messing with these bits is the basis of much of the compression technology we rely on to make it easier to transmit multimedia, because we simply don’t notice that they’ve gone missing.

In a way, then, a lot of the best hiding places for secret information on our networks are a product of our imperfect - or too-perfect - sensory systems: either we aren’t noticing an awful lot, or we’re very good at filtering out noise, depending on how you look at it. If we were all automatons with absolutely perfect perception, it would be much tougher to find any least significant bits into which to dump coded messages.

![]() Follow Christopher Mims on Twitter, or contact him via email.

Follow Christopher Mims on Twitter, or contact him via email.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.