Bulletproofing Cryptography

Much of today’s data security rests on encryption techniques involving mathematical functions that are easy to perform but hard to reverse, such as multiplying two large prime numbers. Factoring the result without knowing either of the prime numbers is very difficult, at least for the computers we use today; it could take thousands of years for even the most powerful supercomputer to identify the original numbers and crack an encrypted message.

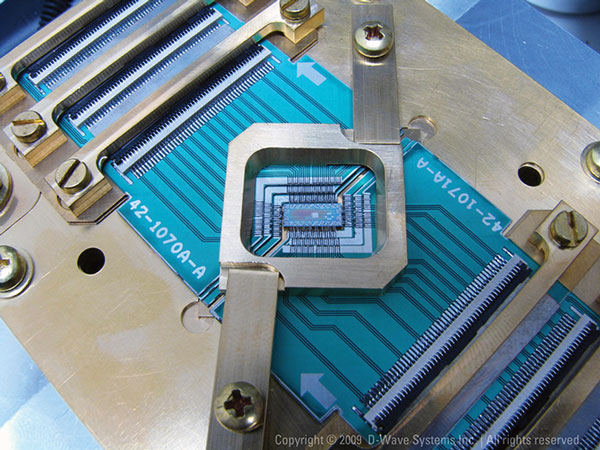

The task would be a snap for a quantum computer, however. (In these computers, a bit need not be just a 0 or a 1; it can exist in an infinite number of intermediate states.) A practical quantum computer is probably at least decades away, but simple demonstrations have already been made. Some researchers warn that such a computer would herald the death of encryption and expose not just new information but also preëxisting material encrypted in the expectation that it would stay secret indefinitely. Imagine if it became possible in 20 years to read electronic medical records being created today.

Alternative systems are being proposed. Lattice-based encryption, for example, relies on the difficulty of determining such things as the shortest vector possible in a given multidimensional lattice; that can be so hard it would stump even a quantum computer. Even though such a computer may not be available for many years, if ever, it’s important to begin developing and deploying better cryptography now so it has time to diffuse throughout cyberspace.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.