The High Cost of Upholding Moore’s Law

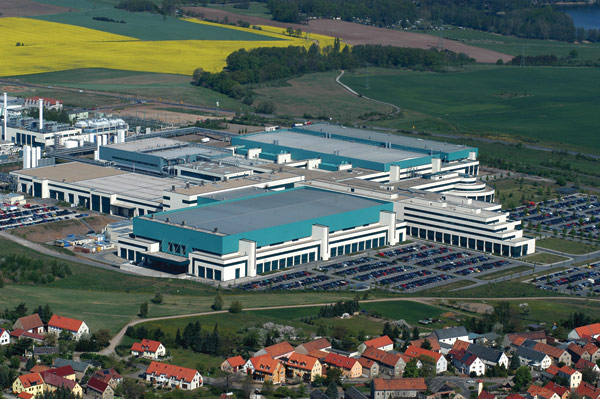

A new leading-edge microchip fabrication facility, or fab, costs $3 billion to $5 billion to build. The high capital cost means that fabs must keep their production lines running at full capacity in order to pay back the money sunk into them. “The most expensive thing on the planet is a half-empty fab,” says Brian Krzanich, general manager of Intel’s manufacturing and supply chain. Consequently, only the highest-volume processor manufacturers–such as Samsung and Intel–are still sole owners and operators of state-of-the-art plants.

Other chip makers either produce lower-performance chips using older, less expensive techniques or outsource manufacturing to companies that specialize in operating semiconductor plants, such as GlobalFoundries (spun out of AMD last year) and the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company. These foundries aggregate high-volume orders from multiple customers to keep production lines humming. GlobalFoundries, with more than $2 billion in annual revenue, expects to expand its annual production capability to 3.8 million wafers by 2014; each wafer will comprise hundreds of chips.

The most advanced mass-produced chips are made with integrated circuits whose smallest features are about 32 nanometers across. The next generation, with 28-nanometer features, will arrive later this year, and 22- and 20-nanometer processors are “well down the path on development,” says Ana Hunter, Samsung’s vice president of foundry services in the United States. These smaller features mean that the constant gain in processor performance that has become familiar over the last 40 years can be expected to continue. Moore’s Law–the prediction that the number of transistors on a chip will double every 24 months–will hold true for at least the next few years.

The most advanced mass-produced chips are made with integrated circuits whose smallest features are about 32 nanometers across. The next generation, with 28-nanometer features, will arrive later this year, and 22- and 20-nanometer processors are “well down the path on development,” says Ana Hunter, Samsung’s vice president of foundry services in the United States. These smaller features mean that the constant gain in processor performance that has become familiar over the last 40 years can be expected to continue. Moore’s Law–the prediction that the number of transistors on a chip will double every 24 months–will hold true for at least the next few years.

But as the elements on a chip become smaller, designing processors is getting tougher. All this means that R&D costs are rapidly increasing. In 2009, around $30 billion, or 17 percent of revenue, went to R&D across the industry–a 40 percent increase over 1999. Fabs are getting more expensive as well; in 1999, a state-of-the-art fab cost roughly $2 billion.

DATA SHOT

Chip makers are trying to contain costs with extensive collaborations. IBM, GlobalFoundries, STMicroelectronics, Toshiba, NEC, Infineon, and Samsung are all working together on developing high-volume manufacturing processes suitable for next-generation chips. Whether the shift toward multicustomer foundries and R&D cost-cutting will let Moore’s Law continue into the next decade, however, is anyone’s guess. In the end, the biggest limitation on silicon chip technology might not be the laws of physics but those of economics.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.