Why Don’t Spammers Get Shut Down Faster?

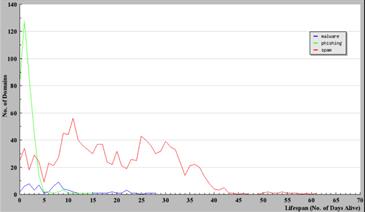

While researching today’s story about crafty phishing techniques, I came across some statistics that reveal the lifespan of various types of nefarious Internet schemes. The chart below, put together by Milcord, a company that collects real-time data about botnets, shows that spammers survive for a couple of months, while phishers typically make it only about five to ten days. Malware schemes are in between.

What’s the reason for this time difference?

Alper Caglayan, Milcord’s president, thinks it’s due to the nature of the victim. “Phishing targets well-known brands, like Citibank, Bank of America, eBay, or Paypal,” he says. “Obviously, these folks are willing to spend a lot of money defending their brands.”

Though ordinary people are the ones who ultimately get burned, phishers can affect the reputations of companies with deep pockets. Caglayan says that some security companies offer service-level agreements that promise to get a phishing site hosted in the U.S. taken down in under an hour.

Spam, on the other hand, has no such highly-motivated opponents. While it’s a nuisance to everyone, no particular company suffers publicly for it, and therefore, the money to halt it simply isn’t there.

Most individuals may want someone to do something about spam, but they end up relying on anti-virus software or intervention from law-enforcement agencies.The motivation to go after and shut down the botnets just isn’t the same.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.