China’s Potent Wind Potential

China has doubled its installed wind power capacity every year for the past five, and is on pace this year to supplant the United States as the world’s largest market for new installations. But researchers from Harvard University and Beijing’s Tsinghua University suggest that the Chinese wind power industry has hardly begun to tap its potential. According to their meteorological and financial modeling, reported in the journal Science last week, there is enough strong wind in China to profitably satisfy all of the country’s electricity demand until at least 2030.

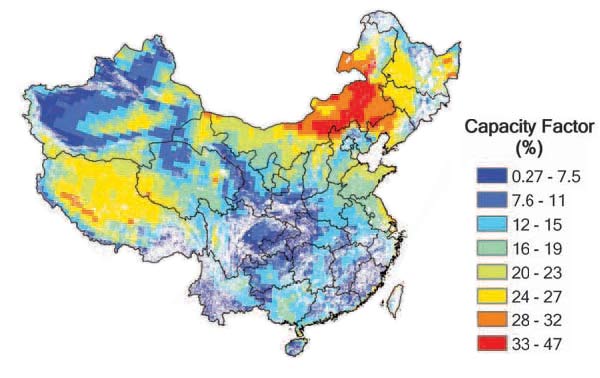

Harvard-Tsinghua project leader Michael McElroy and colleagues quantified China’s wind energy potential by first modeling the availability of wind. To do this, they chopped the Chinese map into parcels 3,335 square kilometers each and used five years of recent meteorological data to generate a wind profile for each parcel. Next, they added industry-standard 1.5-megawatt wind turbines across each parcel (excluding unfriendly terrain such as steep hills, forests, and urban areas) in the model and estimated each parcel’s energy output. Finally, they calculated the cost of the energy that could be produced as a function of the cost of installing the turbines.

The modeling reveals extensive regions, concentrated in northern and western China, where much energy can be generated at costs similar to the government-set energy rates earned by established wind farms, which range from 0.38 to 0.55 Chinese yuan (6 cents to 8 cents) per kilowatt-hour (kwh). For example, the model predicts that wind-farm operators could profitably generate 6.96 trillion kwh of wind energy – more than double China’s annual power consumption of 3.4 trillion kwh and comparable to the projected total demand by 2030 – at a contract price of 0.516 Chinese yuan (7.5 cents) per kwh.

In other words, wind offers a carbon-neutral source of energy to meet China’s power needs for the next two decades. Meeting incremental demand with coal-fired generation, in contrast, would generate 3.5 billion tons per year of carbon dioxide emissions (more greenhouse gas than the European Union expects to release by 2030).

McElroy, a Harvard professor of environmental studies, insists that such ambitious visions are realistic and worth seriously considering. For one thing, 0.516 Chinese yuan is at the low end of the tariffs for future wind farms that China’s National People’s Congress approved last month. For another, China’s wind industry is already outstripping targets “year after year.” China will reach its 2020 target for wind power next year, a decade early, as wind power capacity crests over 30,000 MW, according to the Brussels-based Global Wind Energy Council. By 2020, China is likely to have installed 135,000 MW of wind power capacity, according to analysis by consultancy Emerging Energy Research, based in Cambridge, MA.

However, McElroy acknowledges that China’s grids would need to be smarter and stronger to accommodate the variability of wind energy. In fact, the Global Wind Energy Council says China’s underdeveloped transmission system is already an impediment, delaying the start of energy production from new wind farms. And the group says the problem is becoming more acute as China’s wind developments shift to the wind-rich yet remote regions in the north and west, where the grid is weaker than average and power must travel farther to reach consumers. In China’s northern autonomous region of Inner Mongolia, grid limits are constraining proposed wind projects, according to Sebastian Meyer, director of research for the Beijing-based consultancy firm Azure International.

Meyer says the challenge will be as much administrative and financial as technical. He says that a political imperative for rural development guarantees that wind power will remain popular among local and regional officials, but how to finance the “smartening and balancing of the grid needs to be resolved.” A surcharge of 0.001-0.002 Chinese yuan per kWh that Chinese consumers pay to support integration of renewable energy barely covers the direct cost of patching wind farms into the grids. “Even for this limited end-use, funds have come back to the local grids with considerable delay,” says Meyer.

Then again, says McElroy, China is already aggressively upgrading its power grids to link remote hydropower projects with population centers - a process that could expand to distributing massive generation from notoriously unpredictable wind farms. “China certainly has the know-how to build long-distance high-voltage transmission systems,” says McElroy.

The major grid upgrades already under way in China are making extensive use of continental-scale high-voltage direct-current (HVDC) lines, which remain the stuff of supergrid blueprints in Europe and the United States. “They are leading the world in implementing long-distance transmission schemes,” says Bjarne Andersen, director of U.K.-based consultancy Andersen Power Electronic Solutions and an expert in the ultra-efficient HVDC technology. Andersen says that China already operates HVDC lines carrying 19,860 MW of power, is building lines for another 18,900 MW, and is planning for 17,900 MW more.

And Andersen says China’s power planners are innovating. An 800-kilovolt HVDC link from central Yunnan province to coastal Guangdong, which will be the world’s first when it starts up later this year, is expected to lose 30% less energy in transit than today’s 500 kV lines. Several more 800 kV lines are under construction.

The current grid upgrades mirror what would be needed to transmit remote wind power. Most new transmission lines are designed to drive power from western hydroelectric dams toward eastern megacities such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou, says Andersen. But there are signs that grid planners are beginning to take wind development seriously as well. Construction began last year on a 750 kV AC line to carry electricity from a wind farm in western Gansu province that is one of six national wind power megaprojects approved by the government. Gansu’s wind farm, dubbed the Three Gorges Dam on Land, is slated to grow to 20,000 MW by 2020, at an estimated cost of 120 billion Chinese yuan ($17.5 billion).

McElroy says China’s political situation may also lend itself to adding the required transmission lines. Wind-rich regions such as the ethnically Uyghur northwest are among China’s poorest, and the government has an interest in promoting their economic development. McElroy adds that local opposition, which has stymied transmission projects in North America and Europe for years, is unlikely to stop China’s wind power surge. “The government probably has more power to institute a plan once it’s approved.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.